LiLa4Green

Created on 03-06-2022 | Updated on 04-07-2023

LiLa4Green is a research project that aims to foment participatory creation and the implementation of nature-based solutions in densely built neighbourhoods in Vienna. The project has been developed by an interdisciplinary consortium and its main objective is to bring together experts and residents to collectively address the issue of climate change. The project is an innovative, transferable example of the successful communication of a complex issue that requires expertise in an approachable and inclusive way from experts to non-experts. Hence, its importance lies not only in the replicability of the developed green solutions to neighbourhoods of similar characteristics to improve their microclimatic conditions, but in the transferability of its innovative methodological approach in reaching out and engaging citizens of diverse characteristics in the co-creation of solutions on urban issues that significantly affect their lives and which had been previously overlooked due to lack of awareness.

Its goal is to move beyond climate-resilient considerations and to embrace social priorities, such as improving quality of life, raising local awareness on resilience and achieving acceptance of scientific solutions on environmental issues by non-expert communities. To this end, a Living Lab (LL) approach is employed to engage citizens, stakeholders and decision-makers in the co-creation and implementation of green solutions that collaboratively respond to local emergencies.

Tested in two neighbourhoods in Vienna, the project’s roadmap is targeted on spatially and socially challenged residential areas, characterised by their lack of open public space and green areas, by the dominance of car traffic and the disadvantaged living conditions. LiLa4Green demonstrates an innovative social-scientific approach to dealing with local urban emergencies through enabling user participation facilitated in an inclusive and flexible way that adapts to the social and urban context.

Initiating entity

Austrian Institute of Technology (AIT)

Objectives

Smart user participation for the implementation of climate- and social-resilient solutions in priority residential neighbourhoods

Educational/participatory methods

Scientific Analysis, Urban Living Lab, Green Workshops, On site activities

Context

Environmentally and socially priority neighbourhoods / funded by the Climate and Energy Fund and implemented under the "SMART CITIES - FIT for SET" program.

Place

Neighbourhood Scale, “Quellenstraße Ost” and ‘Kreta’ neighbourhoods in Vienna

Period

Completed / 2018-2021

Duration

3 years

Stakeholders

Research consortium (Austrian Institute of Technology, Technical University of Vienna, Weatherpark, PlanSinn, GRÜNSTATTGRAU and GREX IT), citizens, local stakeholders

Object of study

Neihbourhood Event

Description

Background

Over the last decades, international and national environmental policies have been designed and implemented to counteract the impact of the emerging climate change, this forcing many cities around the globe to adapt their urban environment and update their planning strategies. On a local level, targeted solutions to improve urban microclimates play a catalytic role on the sense of urban comfort, especially in densely built areas lacking green. Such nature-based and cost-effective solutions which provide environmental, social and economic benefits for resilience (European Commision Research and Innovation, n.d.), as well as comprehensive green and blue infrastructure strategies that promote the use of natural processes and vegetation to achieve landscape and water management benefits in an urban context (Victoria State Goverment Department of Environment Land Water and Planning, 2017) can counteract the effects of rising temperatures and provide resilience for cities and inhabitants (Roehr & Laurenz, 2008). However, their implementation and maintenance face many challenges, such as administrative limitations and lack of awareness or acceptance by the local stakeholders and residents (Hagen et al., 2021; Tötzer et al., 2019).

Working to address this challenge in a holistic manner, the LiLa4Green project, as part of the Smart Cities Initiative, aims to foster the implementation of nature-based solutions in the city of Vienna, by integrating a LL approach that focuses on social innovation and knowledge-sharing. The main goals of the project include the collaborative identification of challenges and potentials, the implementation of co-created solutions in the streetscape and the visualisation of the effects of potential solutions in a creative way to raise awareness and activate participants (Hagen et al., 2021).

The project is funded by the Climate and Energy Fund and is carried out by an interdisciplinary consortium consisting of research, academic and community partners. The project’s methodology has been tested in two residential neighbourhoods, ‘Quellenstraße Ost’ in the 10th district and ‘Kreta’ in the 14th district of Vienna. Both neighbourhoods are characterised by dense urban structures and insufficient public and green spaces, and their population consists predominantly of young, low-income immigrant groups who are poorly qualified and which suffer a high unemployment rate (Hagen et al., 2019).

Methodological Approach

The project was implemented along two parallel lines of work. The first refers to a scientific approach conducted by the research consortium. This initiated with the open space and microclimatic analysis of the areas, the results of which were seen in context with the climate of the whole city, concluding to the areas’ characterisation. A demarcation as ‘vulnerable with respect to densification’ (Tötzer et al., 2019, p. 3) reflects the high density and bioclimatic stress of the neighbourhood. The analysis offered valuable insights in identifying priority spots, i.e., small-scale heat islands, and was followed by discussions on greening potentials and recommendations about the areas’ needs and characteristics.

In parallel, a participatory process was initiated in the focus areas to inform the scientific findings on the most problematic locations in the neighbourhood based on the local knowledge and experience of residents and local stakeholders. At the same time, through the establishment of the LL as an alternative to top-down city planning strategies, residents moved from being information facilitators to co-creators.

Following this approach of empowering residents to actively participate in the development of solutions that affect their living environment, the LL investigated ways to raise public awareness on mitigation and measures to facilitate citizens’ adaptation to climate change and to ensure a broad acceptance for the green-blue infrastructure among the general public, through the design and testing of multiple and diverse smart user participation and visualisation methods. A combination of innovative social science methods with the latest digital technology was put forward to facilitate the dissemination of information of the diverse functionalities of green and free spaces, testing also new methods of visualisation of the effects, such as Augmented and Virtual Reality, for more informed decisions (www.lila4green.at). Focusing further on the visibility and traceability (Hagen et al., 2021, p. 393) of the added value of the potential interventions, the monitoring phase included a combination of measurements, simulations and surveys, while in the assessment phase, innovative tools such as crowdsourcing and maps were employed to correlate multiple measurements such as costs and maintenance requirements.

Activities

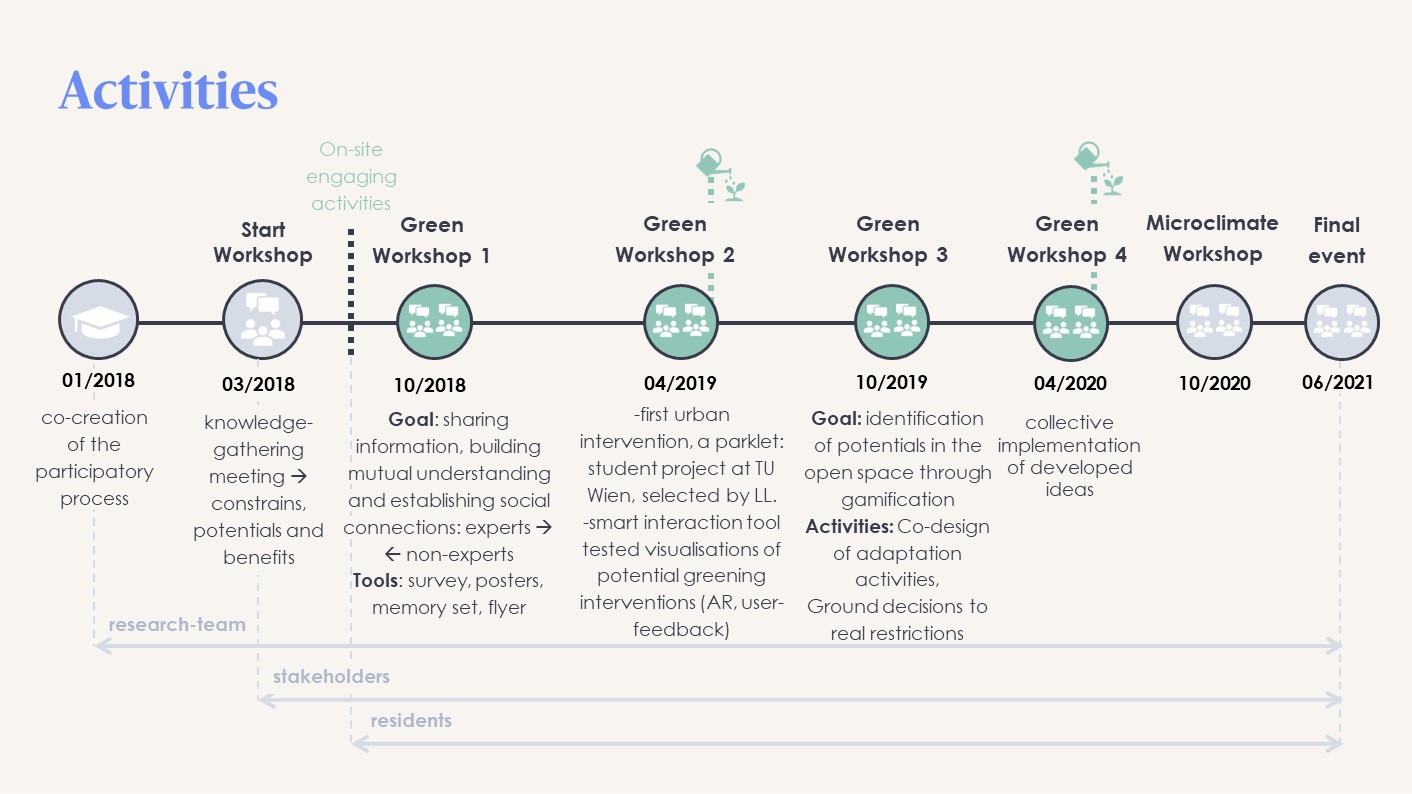

The innovative methodology was tested in practice in a range of different activities organised by the LL that opened the research to citizens and stakeholders in an interactive format. The participatory process initiated with the LiLa4Green research team coming together to design the operation and context of the LL. The activities in the LL began with the ‘Start Workshop’, a knowledge-gathering meeting in which research team members and relevant stakeholders (representatives of municipal agencies and local institutions) came together to discuss constrains, potentials in the project area and the mutual benefits.

This introductory event was followed by the four cornerstones of the project, namely the ‘Green Workshops’ (GWs) that took place every 6 months and involved the research team, stakeholders and citizens. In preparation of each of these four events, a set of activities was organised on site, related to the objectives of the foregoing events, as well as the results of the previous ones. For instance, before the first Green Workshop that focused on ‘sharing information, building mutual understanding and establishing social connections’ (Tötzer et al., 2019, p. 5), the research team conducted on site activation activities which included the creation of a temporary space for conversations using pictures, signs and questions to approach the people passing by, and also engaging them through game-like activities of mapping and voting.

The first workshop started and concluded with a survey. The comparison of the answers of both surveys enabled the organisers to detect changes in the perception of participants on the topic and hence the success of the workshop in the transfer of knowledge. The workshop was organised in two parts that differentiated on the flow of knowledge from the research group to the participants and reversely, using posters, a memory set and a flyer as tools for communication.

Working on the feedback from the first workshop, the second event focused on the realisation of the first urban intervention, a parklet, that was developed as a student project at intended design studios at the TU Wien and then selected by the participants of the LL. Furthermore, using a smart interaction tool with AR technology on site, participants were given the chance to visualise and provide their feedback on potential greening interventions.

Having built trust between the participants and the research team, the third workshop aimed at the identification of the potential uses of the open space through gamification. The participants designed adaptation activities to respond to the scientifically identified conditions and further grounded their decisions to real restrictions, such as budget. In the same workshop, participants tested the AR tool that was further developed by the research team according to the feedback from the second workshop.

Finally, the fourth workshop dealt with the collective implementation of the developed proposals. Due to the pandemic outbreak the workshop was delivered in a digital format and the results were eventually implemented in the summer 2020.

Communication and Sharing Experience

Parallel to the workshops and activities, the consortium gave a great value to the communication and dissemination of LiLa4Green within and outside the focus areas by sending out a frequent newsletter and an Explain Video to attract and maintain participants’ motivation. Surveys and questionnaires were used to incorporate the feedback for the next stages, and experiences were shared via a website. Furthermore, the team created a brochure with the title “In 5 Schritten zum guten Klima” (LiLa4Green, n.d.) to summarise the smart participation methodology in five steps: 1. Prepare the ground and initiate the process, 2. Share knowledge and learn together, 3. Decide and create trust, 4. Designing the future in a playful way, and 5. Specify and implement together. Lastly, aiming to disseminate the knowledge and experiences with the scientific community, the research team actively participated in conferences, presentations, lectures and journals.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank Tanja Tötzer, expert advisor at the Austrian Institute of Technology in Vienna and coordinator of the LiLa4Green project, for the inspiring discussion and generous insights that have helped to write about LiLa4Green.

Alignment with project research areas

Lila4Green is particularly relevant for RE-DWELL’s research on affordable and sustainable housing through a transdisciplinary approach as it brings together three areas: climate research and resilient design, community participation and innovation to address social and environmental emergencies in neighbourhoods and populations that are at risk of vulnerability. The implementation of the project in residential neighbourhoods of disadvantaged urban and social characteristics denotes the overarching focus to improve the quality of life of these neighbourhoods and instigate active citizenship to combat environmental and social issues.

In particular, this project is related to the research area on Community Participation due to its participatory methodology, as well as with the area of Design, Planning and Building, due to its scope of implementing green solutions at the neighbourhood scale to counteract the effects of climate change. In a second level, as a nationally funded project that is also part of an international network of knowledge-sharing, there is also an important relation to the area of Policy and financing (categories Governance, market and financing and Social housing policies).

Within the broader areas of research, three major categories – and further related extensions – best reflect the LiLa4Green project. The first is transient and digital societies which is concerned with to the implementation of physical and digital infrastructures and spaces for urban innovation and knowledge sharing such as the Urban Living Labs, as drivers of social and urban change. Through the Living Lab approach and the interweaving of diverse tools and methods to activate and engage the residents and stakeholders in the co-creation process, the project expands its limits to the spectrum of inclusive design, community planning and co-design.

The second main category is that of green building, that aims at implementing designs that achieve environmental sustainability. Nature-based solutions as well as green and blue infrastructure that are developed and tested during the LiLa4Green project, are successful examples of these designs. As an extension, the project relates to the categories of sustainable planning and urban regeneration. Lastly, the third category is the innovation procurement, as well as housing design education as they relate to the LL’s pillars as an innovation and knowledge-sharing space.

* This diagram is for illustrative purposes only based on the author’s interpretation of the above case study

Alignment with SDGs

Although LiLa4Green has not explicitly associated its targets to the Sustainable Development Goals, several alignments can be drawn with specific goals and targets.

To begin with, SDG 11 sustainable cities and communities and significantly the targets 11.3, 11.6 and 11.7 are reflected in the project’s overarching goal to achieve environmental and social sustainability in the test neighbourhoods, through a participatory approach that aims at creating a healthy neighbourhood, improving the quality of life and safeguarding the residents’ access to open green spaces. Related to this, the integration of a participatory methodology that engages all relevant stakeholders in the co-creation and decision-making processes through innovative methods to align with the Smart Citizens initiative, connects to SDG 16 peace, justice and strong institutions with a great focus on the extrapolation of target 16.7 on the neighbourhood scale, as well as with SDG 9 industry, innovation and infrastructure.

Furthermore, SDG 4 quality education and specifically target 4.7 that refers to education on sustainable lifestyles, is reflected in LiLa4Green Living Lab’s role as a space of creative knowledge sharing on sustainability challenges and solutions through raising awareness and activating the residents and local stakeholders. The initiation of the project by an interdisciplinary research consortium that involved research and academic institutions significantly contributes to addressing this goal.

Moreover, SDG 13 climate action and target 13.3 are connected to LiLa4Green’s main goal to raise awareness and co-create nature-based solutions and green and blue infrastructure in priority neighbourhoods that are mostly affected by the impact of climate crisis and the urban heat wave. Similarly, the implementation of blue infrastructure projects, as well as in the engagement of local communities in the water management also is also related to SDG 6 clean water and sanitation and targets 6.5 and 6.b.

Finally, the project further relates indirectly to the Goals 1. no poverty, 3. Good health and well-being, 7. Affordable and clean energy, 8. Decent work and economic growth, 10. Reduce inequalities, 12. Responsible consumption and production, 17. Partnerships for the goals.

References

European Commision Research and Innovation. (n.d.). Nature-Based Solutions in the EU: Innovating with nature to address social, economic and environmental challenges. Academic Press Inc.

Hagen, K., Gasienica-Wawrytko, B., Meinharter, E., Brossmann, J., Matejka, V., Ratheiser, M., Gepp, W., Erian, P., & Tötzer, T. (2019). LiLa4Green, Begleitendes Living Lab für die Realisierung von grünblauen Infrastrukturmaßnahmen in der Smart City Wien, Bericht zur Potentialanalyse.

Hagen, K., Tötzer, T., Meinharter, E., Millinger, D., Ratheiser, M., & Formanek, S. (2021). How to Make Existing Urban Structures Climate-Resilient? REAL CORP 2021: CITIES 20.50 Creating Habitats for the 3rd Millennium – Vienna, Austria, September, 393–402.

LiLa4Green. (n.d.). In 5 Schritten zum guten Klima MIT LILA4GREEN. Retrieved March 17, 2022, from https://lila4green.at/2021/10/15/die-lila4green-broschuere-ist-da/

Roehr, D., & Laurenz, J. (2008). Living skins: Environmental benefits of green envelopes in the city context. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment, 113, 149–158.

Tötzer, T., Hagen, K., Meinharter, E., Millinger, D., Ratheiser, M., Formanek, S., Gasienica-Wawrytko, B., Brossmann, J., Matejka, V., & Gepp, W. (2019). Fostering the implementation of green solutions through a Living Lab approach - Experiences from the LiLa4Green project. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 323(1).

Victoria State Goverment Department of Environment Land Water and Planning. (2017). Green-Blue City.

www.lila4green.at. (n.d.).

Related vocabulary

Community Empowerment

Participatory Approaches

Placemaking

Social Sustainability

Area: Community participation

Created on 03-06-2022

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 17-02-2022

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 08-11-2023

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 03-06-2022

Read more ->