Let’s talk embodied carbon

Posted on 26-07-2023

I’m happy to report of some good news for once from the UK, although I am a Londoner now living in Barcelona, I am trying to keep my finger on the pulse with the goings-on of all things sustainability back home.

There have been some promising updates regarding embodied carbon, with real steps being taken to actually limit it, rather than just talking about it. But first to clarify what embodied carbon is, the World Green Building council defines it as “the carbon emissions associated with materials and construction processes throughout the whole lifecycle of a building or infrastructure”, the lifecycle refers to extracting raw materials, transportation to factories, manufacturing processes, transporting products to site, construction on site, maintenance and replacements during the use phase, and the end of life phase (i.e. when the building is transformed and hopefully not demolished). Until recently the conversations really centred around operational carbon, which is the energy consumed during the use phase by occupants mostly for heating, cooling, lighting, and powering appliances and devices.

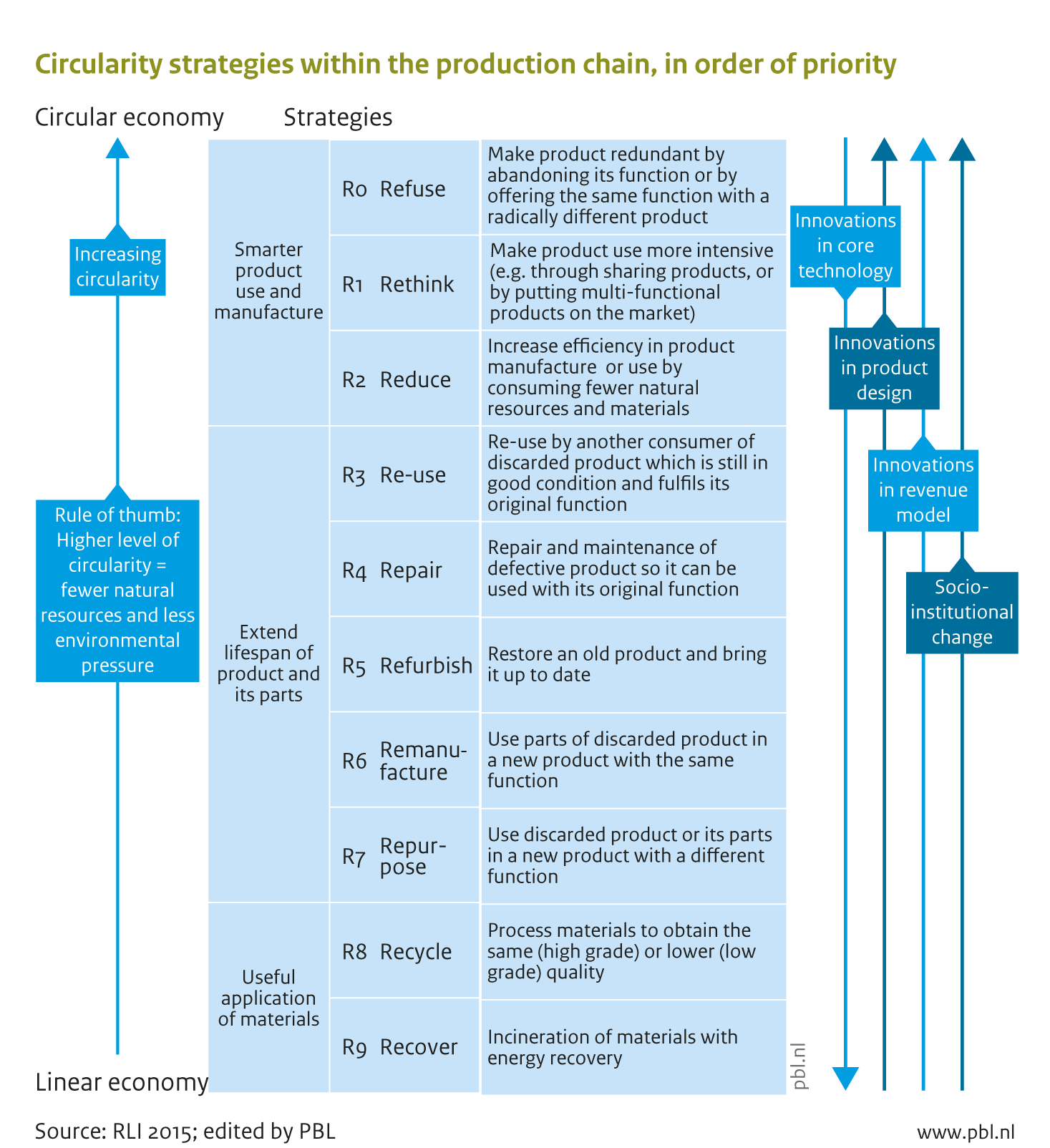

To reduce the amount of embodied carbon that is put out into the world, the first practical step is to stop and think whether a project should be built at all, as per the R ladder by the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, which goes beyond the famous 3R’s (reduce reuse recycle). Given that we do build in most cases, the focus must be on reusing as many materials as possible to reduce embodied carbon, rather than recycling (downgrading), landfilling, backfilling, and incinerating.

Here are some of the good discussions going on:

- The RIBA has launched a new prize championing reuse called the Reinvention Award that “recognises achievement in the creative reuse of existing buildings through transformative projects that improve environmental, social, or economic sustainability”. This will incentivise architectural practices to push for reuse and in time provide excellent case studies for others to follow suit.

- Oxford street’s Art Deco M&S building has been saved from demolition after a long campaign launched back in 2021. Knocking the building down would have generated almost 40,000 tonnes of embodied carbon and acted counter to the UK’s net-zero targets. To stop more projects like these trying to get through, it would be extremely helpful to have a tax reform removing VAT on refurbishment projects – whereas in contrast new build projects (which often entail demolition) are currently exempt.

- Steps are being taken to regulate embodied carbon slowly, but promisingly. The push has come from industry with the Part Z proposal and a campaign launched by ACAN UK in February 2021. In February this year the Carbon Emissions (Buildings) Bill went for its second reading. The UK Parliament's Environmental Audit Select Committee’s 2022 report highlighted the fact that current policy inadequately addresses the need to reduce embodied carbon, develop low-carbon materials, or prioritise reuse and retrofit. Whilst “[ot]her countries and some UK local authorities are already requiring whole life carbon assessments to be undertaken. This leaves the UK slipping behind comparator countries in Europe in monitoring and controlling the embodied carbon in construction. If the UK continues to drag its feet on embodied carbon, it will not meet net zero or its carbon budgets.” The Netherlands, Finland, Sweden, Denmark, and France have already introduced regulation on whole-life carbon emissions. Apparently, the UK is considering including regulating embodied carbon in 2025 building regulations.

Some outgoing thoughts:

All buildings should be built as monuments, meaning we need to literally build in value so that they are considered worth keeping in the future. Today developers, insurers, and designers take too much of a short-term view to the detriment of building quality. What’s more, we need to put more thought into how we can better design buildings to be dismantled and adapted in the future to deal with changing needs and climate change. We have countless world heritage and listed buildings that have stood for centuries that have been reconfigured and maintained throughout time. This level of protection should be afforded to all buildings to limit further carbon emissions.

Re-skilling: There is a great need to re-train current built environment professionals and overhaul academic curriculums to reflect the skills needed to prevent further destruction of biodiversity and climate change. That means rather than striving to build whatever the client wants - regardless of potential negative environmental impacts – the priority should be to make sustainability focussed design decisions. That is at least until legislation catches up.

High-tech solutions are not the answer, unquestioningly embracing new technologies such as AI and the ubiquitous use of smartphones is having negative and even dangerous effects on our lives. The same can be said for the over-reliance of smart systems, mechanical solutions, and overengineering in the built environment. This quote from a recent report by Unesco about the overuse of digital technology on learning outcomes and economic efficiency also applies to construction: “Not all change constitutes progress. Just because something can be done does not mean it should be done.” An example of high-tech energy efficient solutions masking the embodied carbon cost is Foster + Partner’s Bloomberg building which claimed to be the “world's most sustainable office building” and was awarded BREEAM’s highest rating Outstanding in 2017, despite the high embodied carbon that went into building it. Since the invention of electricity, we have relied heavily on it to heat, cool, and light our buildings and homes and have turned our backs on passive strategies which rely less on the production of electricity and the extraction of an increasing number of critical materials.

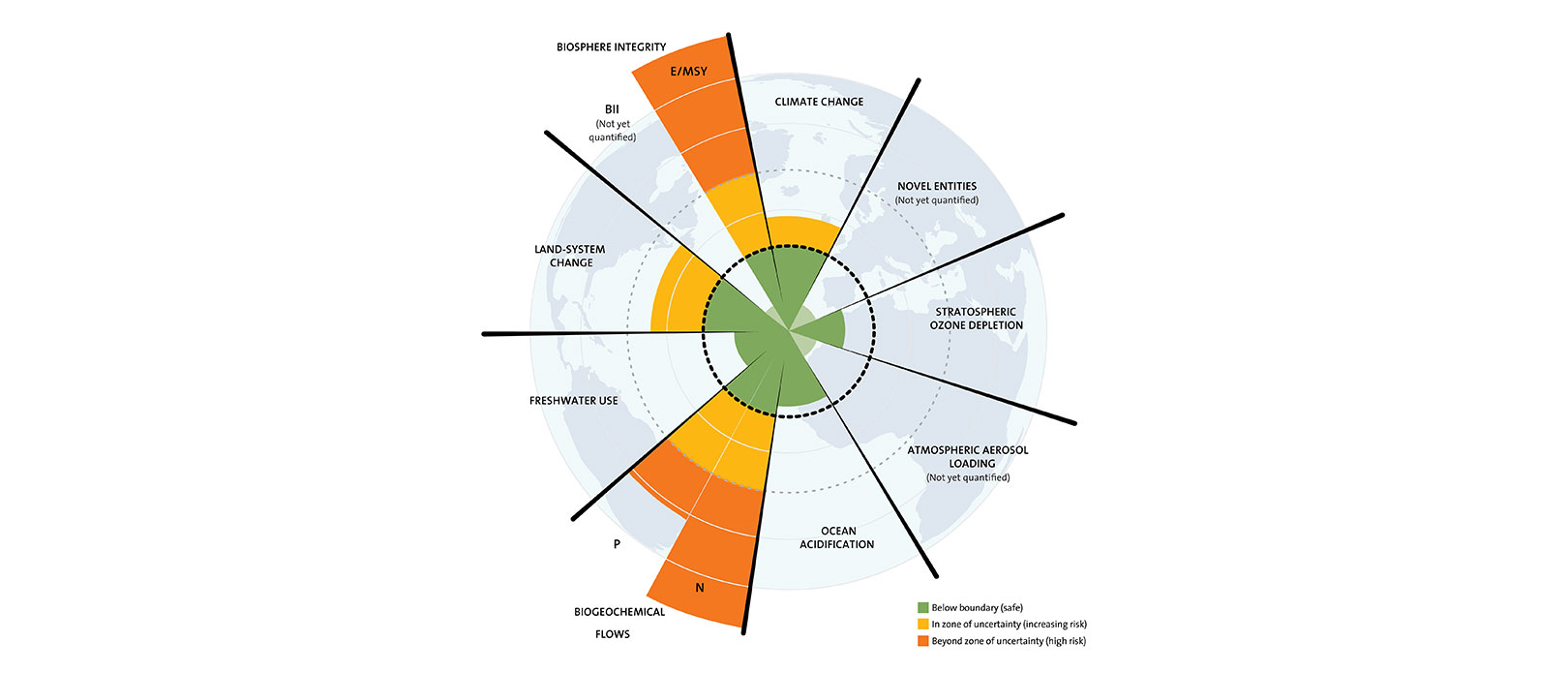

It's not all about embodied carbon. It’s important to bear in mind that carbon is not the only cause of climate change (methane is another contributing greenhouse gas); climate change itself is also just one of nine planetary boundaries identified by the Stockholm Resilience Centre, which are moving towards tipping points and endangering the earth’s stability.

Although these last remarks sound quite existential, I’d like to bring the focus back to the positive moves happening back home (and abroad). The seemingly small wins of promoting reuse, actively preventing demolition, and regulating embodied carbon are the foundations of building a sustainable future.

Sources

World Green Building Council’s embodied carbon definition found in report https://worldgbc.org/advancing-net-zero/embodied-carbon/

R ladder by the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency https://www.pbl.nl/en/publications/circular-economy-measuring-innovation-in-product-chains

RIBA Reinvention prize https://www.architecture.com/awards-and-competitions-landing-page/awards/RIBA-Reinvention-Award#:~:text=The%20Reinvention%20Award%20is%20a,%2C%20social%2C%20or%20economic%20sustainability

M&S building saved from demolition https://www.dezeen.com/2023/07/20/marks-spencers-oxford-street-flagship-saved-demolition/

Proposed Part Z regulating embodied carbon in the UK https://part-z.uk/

ACAN UK’s regulating embodied carbon campaign https://www.architectscan.org/embodiedcarbon

The Stockholm Resilience Centre planetary boundaries https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries.html

Related cases

The Sutton Estate Regeneration, Chelsea

Created on 25-10-2024