Saskia Furman

ESR2

Host university

B1 - School of Architecture La Salle, Ramon Llull UniversitySaskia Furman is an Architect with an avid interest in social and environmental sustainability. Her range of practical experience includes residential, listed buildings, community buildings and low-carbon retrofit of existing homes, contributing to the ongoing European funded project, Homes As Energy Systems (HAES). She continues to investigate community-led cooperative housing design through her collaboration with the Greater Manchester Commoners Cooperative (GMCC).

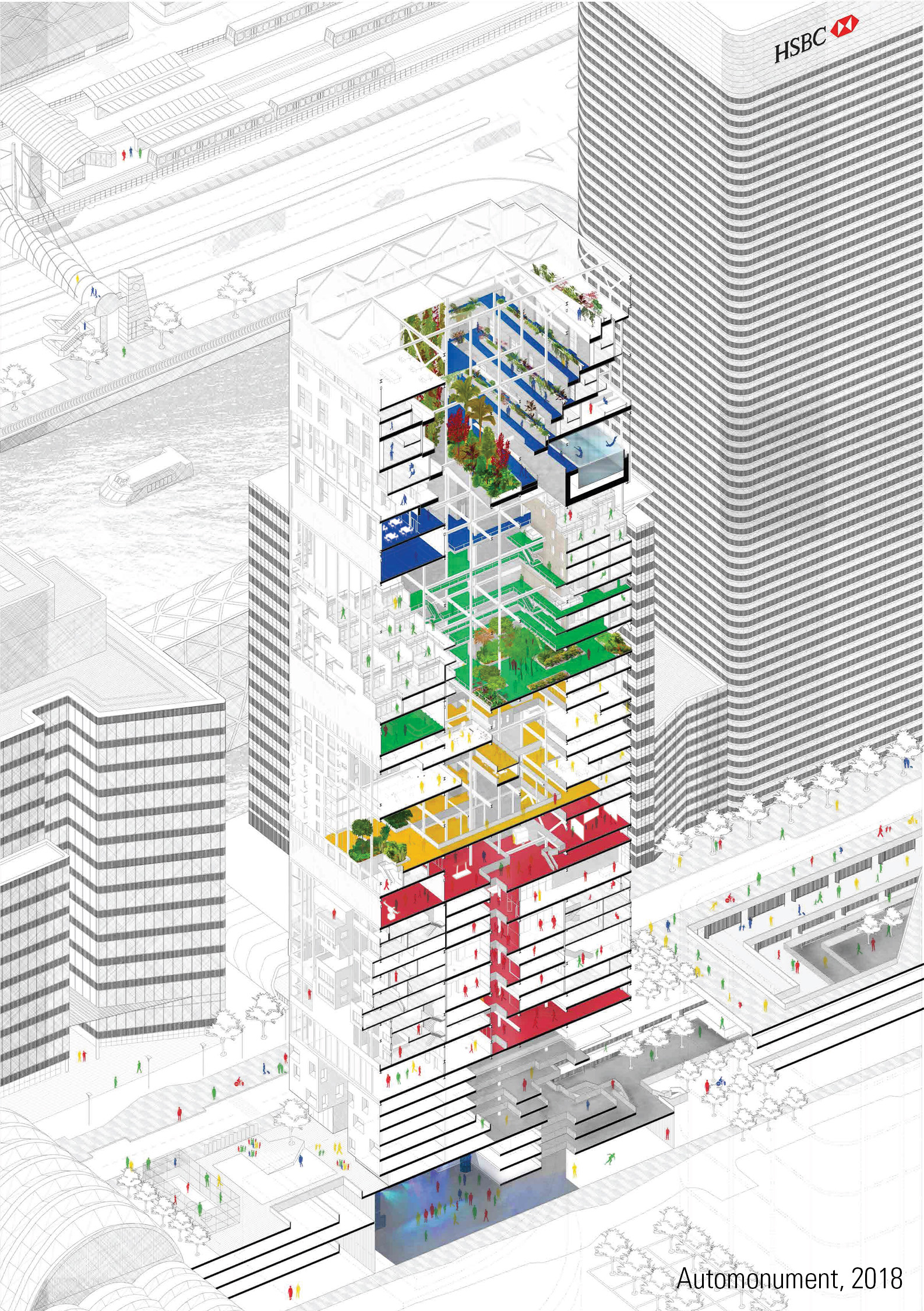

After completing a Bachelor of Architecture at the Manchester School of Architecture, Saskia studied for a Master of Architecture at Liverpool University, where the investigation into both the pragmatic and societal results of automation led to a new housing typology and the award-winning thesis - Automonument.

Saskia’s international study includes: London workshop How Do We Live?; Hello Wood design-build project Caravanserai, Hungary; Erasmus exchange, Germany; and investigation into the social, political and cultural context of the Inhotim Institute, Minas Gerais, Brazil, where she immersed herself in Brazilian culture and language. Based in Barcelona, she will be investigating how to adapt European social housing stock to meet the needs of modern and emerging households.

February, 04, 2025

December, 08, 2023

September, 07, 2023

November, 20, 2022

March, 18, 2022

September, 15, 2021

Upgrading social housing to meet the socio-economic needs of today’s dwellers: A framework for sustainable retrofit.

European social housing peaked in the post-war period. Predominantly designed and constructed by institutional stakeholders using top-down approaches—including architects, planners, engineers, and policy makers—the deregulation of building standards, poor maintenance, and lack of investment, has led to disrepair. Poor insulation, poor energy performance, thin walls, cold, damp, and mould all contribute to the desperate need for retrofit of this housing stock. Unfortunately, over the last few decades, there is evidence to suggest that residents have little to no autonomy (and often lack the financial means) over repair and maintenance and top-down decision-making by building owners is favoured. Yet this method of retrofit neglects inclusive stakeholder engagement in retrofit processes, imposes living standards and conditions onto marginalised groups without integrating their needs, and generates outcomes unfit for purpose.

Recent studies in retrofit suggest that residents are experts in the way they live and should be key contributing stakeholders in retrofit design. Non-energy benefits are more important to residents than energy-related benefits, particularly social housing residents who require pragmatic solutions that differ from homeowners. Despite this, the prioritised method of deep energy retrofit (DER) favours three technical improvements: (1) enhancing the building fabrics’ thermal properties; (2) improving systems efficiency; and (3) renewable energy integration. Performance gaps can be as high as five times the predicted energy consumption, however, driven by the rebound effect, the prebound effect, occupant behaviour, improper installation, and simulation uncertainties. Integrating residents’ perspectives in retrofit design, alongside expert input, can help achieve holistic sustainable outcomes—social, environmental, and economic—that close performance gaps by increasing energy performance, affordability, health and wellbeing, quality of life, and user empowerment, simultaneously closing the performance gap.

This thesis examines how resident participation can improve social housing retrofit outcomes by using a mixed methods approach through: (1) a systematic literature review examining shifting terminology and discourse from social housing to affordable housing in England; (2) a semi-systematic review of resident participation in social housing retrofit; (3) qualitative analysis of stakeholder interviews exploring retrofit decision-making processes; (4) focus group research investigating residents’ values in social housing retrofit; and (5) case study analysis of exemplar social housing retrofit projects across Europe. Reflexivity, power relations, and outsider status are considered to socially position the research in relation to participating stakeholders.

The study addresses the following questions: Could the participation of people living in social housing improve retrofit solutions more than end point performance targeted retrofit? How can social housing retrofit be safeguarded for future tenants? Is deep energy retrofit the best approach for holistic sustainability? What do inhabitants include as important in retrofit, that is not included in the retrofit energy process?

Through this comprehensive analysis, the thesis develops a framework for socially inclusive, holistic retrofit to engage with stakeholder groups. The project discusses the sustainable upgrading of existing social housing stock aligned with the triple bottom line of sustainability, prioritising social and environmental improvements and economic considerations. The findings result in good practice guidance for high-level stakeholders to embed social housing residents in retrofit decision-making processes.

Reference documents

Upgrading Social Housing to meet the Socio-economic needs of Today’s Dwellers: a framework for sustainable retrofit.

European social housing peaked in the post-war period. Predominantly designed and constructed by top-down stakeholders—including architects, planners, engineers, and policy makers—the deregulation of building standards, poor maintenance, and lack of investment, has led to disrepair. Poor insulation, poor energy performance, thin walls, cold, damp, and mould all contribute to the desperate need for retrofit. Residents have little to no autonomy (and often lack the financial means) over repair and maintenance and top-down decision-making by building owners is favoured. Yet this method of retrofit neglects inclusive stakeholder engagement in retrofit processes, imposes living standards and conditions onto marginalised groups without integrating their needs, and generates outcomes unfit for purpose.

Residents are experts in the way they live and should be key contributing stakeholders in retrofit design. Non-energy benefits are more important to residents than energy-related benefits, particularly social housing residents who require pragmatic solutions that differ from homeowners. Despite this, the prioritised method of deep energy retrofit (DER) favours three technical improvements: (1) enhancing the building fabrics’ thermal properties; (2) improving systems efficiency; and (3) renewable energy integration. However, performance gaps can be as high as five times the predicted energy consumption, driven by the rebound effect, the prebound effect, occupant behaviour, improper installation, and simulation uncertainties. Integrating residents’ perspectives in retrofit design, alongside expert input, can help achieve holistic sustainable outcomes—social, environmental, and economic—by increasing energy performance, affordability, health and wellbeing, quality of life, and user empowerment, simultaneously closing the performance gap.

The focus of this thesis is to develop a new process for socially inclusive, holistic retrofit to engage with stakeholder groups. Reflexivity, power relations, relative privilege, and my outsider status will all be considered to socially position myself as the researcher in relation to participating stakeholders, thus framing the investigation with strong objectivity. In this way, inclusive participatory action research will empower underrepresented groups to engage in retrofit processes.

The following questions will be addressed: Could the participation of people living in social housing improve retrofit solutions more than end point performance targeted retrofit? How can social housing retrofit be safeguarded for future tenants? Is DER the best approach for holistic sustainability? What do inhabitants include as important in retrofit, that is not included in the retrofit energy process?

Through participatory research, different processes of social housing retrofit will be investigated. The following questions with two high level stakeholders (third sector housing companies and designers) guiding the retrofit process will be addressed: How did retrofit occur? Why did retrofit occur this way? Who was involved in the retrofit process? What were the objectives? And what role do residents play in decision-making processes? Focus group research with inhabitants will explore how resident satisfaction, health and wellbeing, and quality of life have been impacted by retrofit decisions.

The project will discuss the sustainable upgrading of existing social housing stock in line with the triple bottom line of sustainability, prioritising social and environmental improvements and touching on the economic. From the results, a good practice guide for high level stakeholders to embed social housing residents in retrofit decision-making will be developed.

Reference documents

Upgrading social housing to meet the socio-economic needs of today’s dwellers: A framework for sustainable retrofit

European social housing peaked in the post-war period. Predominantly designed and constructed by top-down stakeholders—including architects, planners, engineers, and policy makers—the deregulation of building standards, poor maintenance, and lack of investment, has led to disrepair. Poor insulation, poor energy performance, thin walls, cold, damp, and mould all contribute to the desperate need for retrofit. Residents have little to no autonomy (and often lack the financial means) over repair and maintenance and top-down decision-making by building owners is favoured. Yet this method of retrofit neglects inclusive stakeholder engagement in retrofit processes, imposes living standards and conditions onto marginalised groups including women and other groups at risk of vulnerability without integrating their needs, and generates outcomes unfit for purpose.

Residents are experts in the way they live and should be key stakeholders in the co-design of retrofit plans. Non-energy benefits are more important to residents than energy-related benefits, particularly social housing residents who also require pragmatic solutions that differ from homeowners. Despite this, the prioritised method of deep energy retrofit (DER) favours three technical improvements: (1) enhancing the building fabrics thermal properties; (2) improving systems efficiency; and (3) renewable energy integration. However, performance gaps can be as high as five times the predicted energy consumption, driven by the rebound effect, the prebound effect, occupant behaviour, improper installation, and simulation uncertainties. Integrating residents’ perspectives in retrofit design, alongside expert input, can help achieve holistic sustainable outcomes – social, environmental, and economic – by increasing energy performance, affordability, health and wellbeing, quality of life, and user empowerment, simultaneously closing the performance gap.

The focus of this thesis is to develop a new process for socially inclusive, holistic retrofit to engage with stakeholder groups. Reflexivity, power relations, relative privilege, and my outsider status will all be considered to socially position myself as the researcher in relation to participating stakeholders, thus framing the investigation with strong objectivity. In this way, inclusive participatory action research will empower women and underrepresented groups to engage in retrofit processes.

The following questions will be addressed: Could the participation of people living in social housing improve retrofit solutions more than end point performance targeted retrofit? How can social housing retrofit be safeguarded for future tenants? Is Deep Energy Retrofit (DER) the best approach for holistic sustainability? What do inhabitants include as important in retrofit, that is not included in the retrofit energy process?

Through the exploratory case study methods umbrella, I will investigate different processes of social housing retrofit. I will investigate the following questions with two high level stakeholders (policy makers and designers) guiding the retrofit process: How did retrofit occur? Why did retrofit occur this way? Who was involved in the retrofit process? What were the objectives? And what role do residents play in decision-making processes? I will also conduct research with inhabitants to explore how resident satisfaction, health and wellbeing, and quality of life have been impacted by retrofit decisions.

The project will discuss the sustainable upgrading of existing social housing stock in line with the triple bottom line of sustainability, prioritising social and environmental improvements and touching on the economic. From the results, I will develop a good practice guide for high level stakeholders to engage social housing residents in retrofit decision-making.

Keywords: Social Housing, Retrofit, Social sustainability, Environmental sustainability

Upgrading social housing to meet the socio-economic needs of today’s dwellers: A framework for sustainable retrofit

Construction of social housing in Europe peaked in the post-war period and was predominantly designed and constructed in a top-down fashion by stakeholders including architects, planners, engineers, and policy makers. Through the deregulation of building standards, poor maintenance and lack of investment, social housing across Europe has fallen into disrepair. Poor insulation, poor energy performance, thin walls, cold, damp, and mould all contribute to the desperate need for retrofit. However, top-down decision-making continues to neglect inclusive stakeholder engagement in retrofit processes that often lead to outcomes not fit for purpose.

The large scale retrofit of residential building stock must defend the need to house people in accessible, inclusive homes they can afford. Housing associations, local authorities, large housing providers and other stakeholders need to be convinced that inclusive, bottom-up retrofit is a necessary economic decision. This is because it will facilitate a long-term return-on-investment through lower maintenance costs, reduced crime rates, positive educational outcomes, and improved mental and physical health and wellbeing of residents.

While energy retrofit can occur as deep, partial, or overtime, the prioritised method of deep energy retrofit favours high energy performance targets through airtightness, mechanical systems, thermal insulation, and renewable energies. As social housing is usually state owned and managed by municipalities and third sector housing associations, a top-down approach to retrofit often occurs because residents have little to no autonomy (and often lack the financial means) over repair and maintenance. Yet this method of retrofit imposes living standards and conditions onto marginalised groups including women and other groups at risk of vulnerability without integrating their needs.

The focus of this thesis is to develop a new process for socially inclusive, holistic retrofit using feminist methodologies to engage with stakeholder groups. Reflexivity, power relations, relative privilege, and my outsider status will all be considered to socially position myself as the researcher in relation to participating stakeholders, thus framing the investigation with strong objectivity. In this way, inclusive participatory action research will empower women and underrepresented groups to engage in retrofit processes.

By revisiting the retrofit process using feminist methods to engage with stakeholders, I will investigate how inclusive retrofit can lead to positive outcomes for residents’ health and wellbeing alongside environmental benefits. The use of feminist methodologies leads to better, more inclusive results because multiple underrepresented groups are explored through the lens of women, including children, the elderly and the less able-bodied. When the results are better from using feminist methodologies, this immediately will empower women. The following questions will be addressed: Could the participation of people living in social housing improve retrofit solutions more than end point performance targeted retrofit? How can social housing retrofit be safeguarded for future tenants? Is Deep Energy Retrofit (DER) the best approach for holistic sustainability? What do inhabitants include as important in retrofit, that is not included in the retrofit energy process?

Through the exploratory case study methods umbrella, I will investigate different processes of social housing retrofit. I will investigate the following questions with two high level stakeholders (policy makers and designers) guiding the retrofit process: How did retrofit occur? Why did retrofit occur this way? Who was involved in the retrofit process? What were the objectives? And what role do residents play in decision-making processes? I will also conduct research with inhabitants to explore how resident satisfaction, health and wellbeing, and quality of life have been impacted by retrofit decisions.

The project will discuss the sustainable upgrading of existing social housing stock in line with the triple bottom line of sustainability, prioritising social and environmental improvements and touching on the economic. From the results, I will develop a comprehensive multi-criteria framework that suggests what type of renovations should occur, how they should occur, and identify the multiple actors and stakeholders that should be engaged in the process, along with a good practice guide.

Upgrading social housing to meet the socio-economic needs of today’s dwellers, and the environmental needs of the planet: A framework beyond retrofit.

Despite the disparity between their meanings the term social housing is often used synonymously with affordable housing. Alongside the increased commodification of housing, this shift in language has facilitated a wider paradigm shift away from the welfare state and towards individualism. The project will discuss the sustainable upgrading of existing social housing stock – initially built as state-provided housing for different groups – in line with current sustainability targets including the triple bottom line of sustainability: social, environmental, and economic.

Increased resident satisfaction is a vital agenda for sustainable social housing renovation, and a multidimensional challenge: social, economic, and environmental. The socio-economic characteristics of social housing dwellers, the surrounding infrastructure including access to amenities and transport, and building energy performance, all converge to impact satisfaction with quality of life.

The necessity to low carbon retrofit housing is a widely accepted agenda throughout the construction industry, policy, and beyond. Retrofit schemes such as the EU’s Renovation Wave aim to combat climate change and assist in the post COVID-19 economic recovery by creating jobs. However, a major obstacle for all housing providers outside the luxury market remains: how to complete retrofit while maintaining affordability?

Commodification of housing has facilitated the migration of social housing over to the private sector, leaving mixed-tenure ‘pepper-pot’ buildings that make retrofit decisions difficult to agree. Meanwhile, the current state of affordable housing is not affordable for all socio-economic groups. Whilst we are currently transitioning to low carbon housing, the large scale retrofit of residential building stock must defend the need to house people in homes they can ‘afford’, rather than upgrading existing social housing stock and selling it to the private market. Housing associations, local authorities, large housing providers and other stakeholders need to be convinced that large scale retrofit is a necessary economic decision that will facilitate a long-term return-on-investment through lower maintenance costs, reduced crime rates, positive educational outcomes, and increased mental and physical health and wellbeing. Long term affordability must be considered throughout the renovation to deter gentrification.

The objective of this research is to develop a matrix for mid- to large-scale housing renovation to deliver affordable and sustainable housing. Organised under broad categories, including urbanity, sustainability, social, connectivity and more, the framework will identify key issues to be improved, such as the building envelope, internal layout, social mix, safety, and energy efficiency. I will then analyse and inform the set of criteria against several case studies and precedents to assess the successes and failures of existing social housing stock. Chosen precedents for investigation will be partly renovated post-war European social housing. Deeper case studies will be identified alongside consultations with INCASÒL and Housing Europe to determine an optimal set of criteria and provide rich data sets for further analysis during secondments; these include post occupancy evaluation, energy performance data, and access to stakeholders for interview.

The following questions will be addressed during case study analysis: How long should evaluation of each case study take place? What problems were identified by renovations and how were solutions found? What did the renovators want to achieve? How do the renovations align with sustainability agendas such as the SDG’s? How has renovation impacted residents’ lives, post occupancy?

From the results of the matrix, I will originate a comprehensive multi-criteria framework that suggests what renovations should occur, why they should occur, and identify the multiple actors and stakeholders that will benefit, along with a best practice guide for easily digestible information.

Reference documents

Adapting European Social Housing to meet the Socio-Economic needs of Today’s Dwellers, and the Environmental needs of the Planet: A Framework for Renovation

Despite the disparity between their meanings the term social housing is often used synonymously with affordable housing. The project will discuss the upgrading of existing social housing stock – initially built as state-provided housing for different groups – to affordable (still a contested term) and sustainable housing, in accordance with the current Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s)

When renovating existing social housing we must address the socio-economic characteristics of today’s dwellers, the surrounding infrastructure, and energy efficiency standards.

The objective of this research is to develop a matrix encompassing the multiple dimensions and issues to consider in a mid- to large-scale renovation programme. Organised under broad categories, including urbanity, sustainability, social, connectivity and more, the framework will identify key issues to be improved, such as the building envelope, internal layout, social mix, safety, and energy efficiency. I will then analyse the set of criteria against a number of case studies to assess the successes of existing social housing stock and areas to be improved. The chosen case studies will be post-war European social housing that has been partly renovated since construction. Consultations with INCASÒL will help determine an optimal set of criteria, as well as provide a rich data set for further analysis during my secondment.

The following questions will be addressed during case study analysis: How long should evaluation of each case study take place? What problems were identified by renovations and how were solutions found? What did the renovators want to achieve? How do the renovations align with the SDG’s?

From the results of the matrix I will originate a comprehensive multi-criteria framework that suggests what renovations should occur, why they should occur, and identify the multiple actors and stakeholders that will benefit.

Reference documents

Housing Europe Secondment: When Technical Retrofit Meets Social Value

Posted on 22-11-2024

Secondments

Read more ->

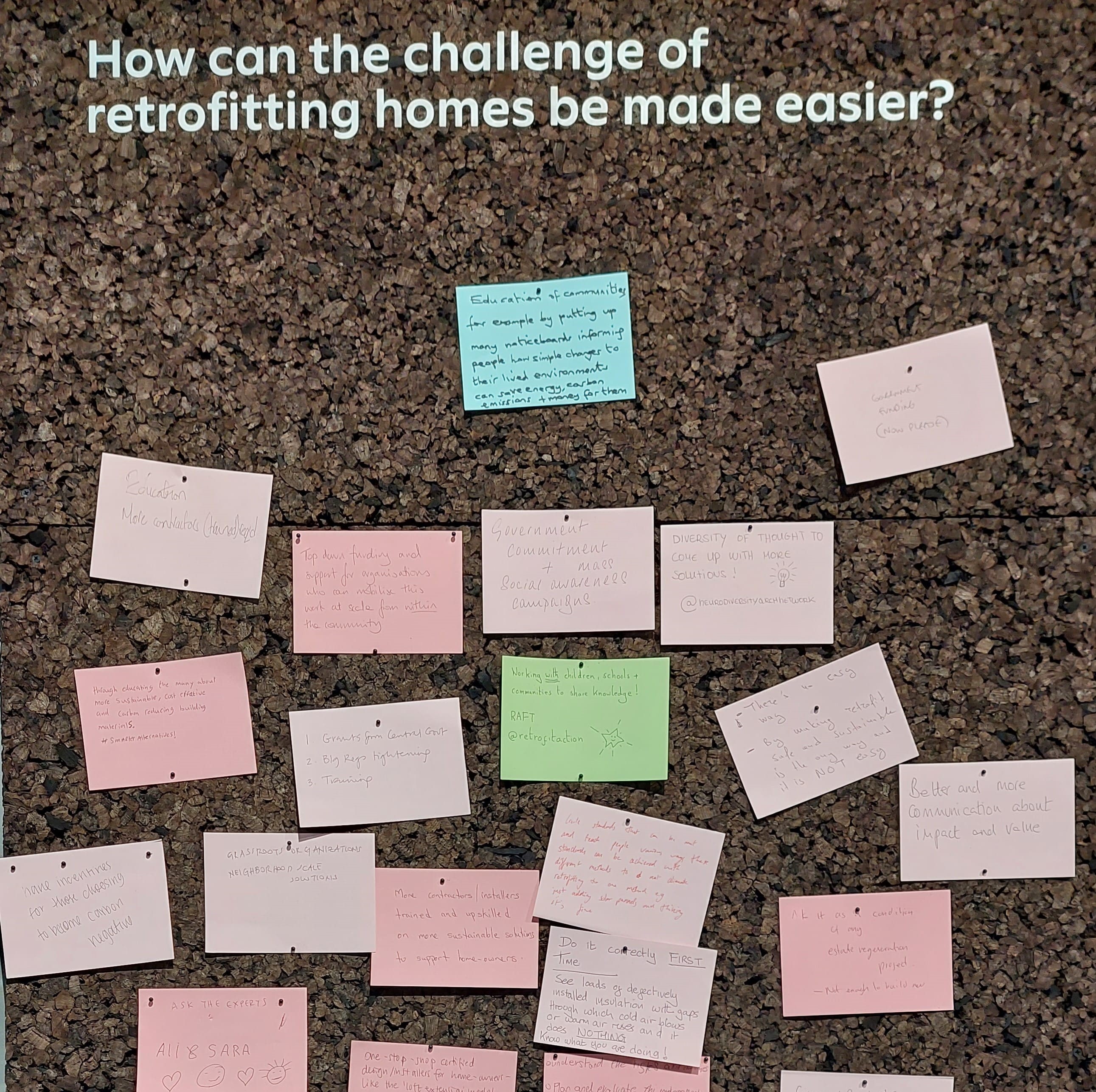

Retrofit and Social Engagement | We can do better

Posted on 13-07-2023

Summer schools, Reflections

Read more ->

ISHF 2023: “At the end of the day, we are all here for the same reason. And we have to look out for each other”

Posted on 16-06-2023

Conferences, Workshops

Read more ->

Retrofit and The Social Agenda

Posted on 08-05-2023

Secondments

Read more ->

Bridging the Retrofit Gap: Climate, Culture, and Infrastructure | Future Build 2022 | International Women’s Day

Posted on 08-03-2022

Conferences

Read more ->

Isolation?

Posted on 26-07-2021

Workshops

Read more ->

LILAC_Low Impact Living Affordable Community_Leeds

Created on 15-11-2024

HOUSEFUL: Els Mestres, Sabadell

Created on 12-03-2025

The Sutton Estate Regeneration, Chelsea

Created on 25-10-2024

Energy Retrofit

Housing Retrofit

Indoor Thermal Comfort

Performance Gap in Retrofit

Sustainability

Techno-optimism

Thermal Insulation & Airtightness

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 23-05-2022

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 16-02-2022

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 20-09-2022

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 08-09-2023

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 19-09-2021

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 14-10-2024

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 25-10-2024

Read more ->Furman, S. (2022, June). The emergence of affordable housing and its relationship to social housing: The history of housing commodification in England. Arquitectonics: Mind, Land & Society, 20th International Conference, Barcelona, Spain.

Posted on 28-02-2026

Conference

Read more ->