Sustainable social housing: a myth, trend or an inescapable fait

Posted on 09-01-2024

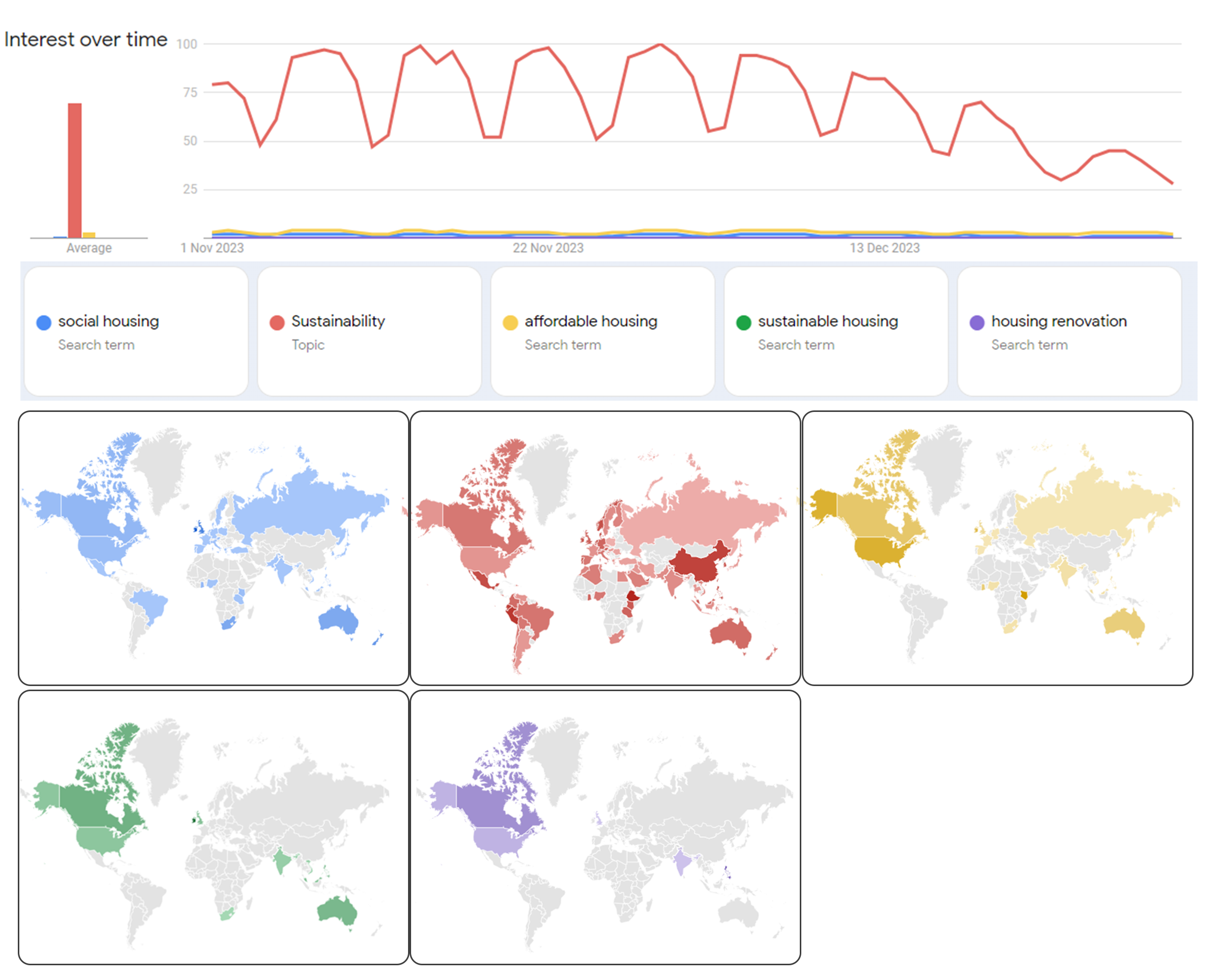

The study of indirect connotations in metadata, especially those generated by artificial intelligence, is a curiosity catalyser. Therefore, I undertook a comparative analysis of the frequency with which key terms such as social housing, sustainability, affordable housing and housing renovation were queried in search engines worldwide between 1 November and 31 December 2023. This data set, known as a “trend” or “interest over time” is measured on a 100-point scale. During this period, sustainability scored an average of 70 points on trend, while social housing and housing renovation slightly recorded 1 point each and affordable housing by 3 points (see Figure 1). It is also worth noting that similar results appear when the time frame is extended to a full year or even five years. Interpreting this data with a degree of scepticism and caution, it appears that sustainability retains its prominent position as the dominant trend. Meanwhile, other vital issues that directly impact our society do not attract comparable interest.

Assuming the previous introduction has captivated your interest. Let me explain why this date and these terms. The date is related to my secondment to Housing Europe, where I gained in-depth experience working with dedicated professionals dealing with the various challenges in the housing sector. Meanwhile, the terms are critical objectives of the RE-DWELL project, which derive from its primary goal of creating a framework for affordable and sustainable housing across Europe. This confluence of dates and terms leads us to a compelling question: what if we were to summarise these terms into a single adjective for a genre of social housing? And then, what constitutes an environmentally sustainable social housing? The following sections, therefore, draw on the insights gained during the secondment to answer these questions and offer a nuanced perspective on the interplay between sustainability, social housing and regulatory frameworks.

What constitutes an environmentally sustainable social housing?

“It has affordable rent, but also affordable energy, that means heating, cooling, lighting and obviously the means of the family. One that is accessible, in term of meeting the individual requirements of occupants. Also one that is in reach of key services, employment, shopping, medical services […]. Access to nature, ensure that resident have access to fresh air, also consideration to acoustics and noise. […] But if we look at sustainability I suppose not from the perspective of occupants but the society, […] it needs to limit the production of energy needed.” (S. Edwards, personal communication, November 2023).

A triad of connotations can be derived from this. First, affordability and social housing are so closely intertwined that discussion of the latter presupposes consideration of the former, especially when viewed from the perspective of the welfare state. Secondly, the definition from the perspective of the urban fabric goes beyond the material structure and encompasses the city's intangible services. This is directly related to economic aspects such as income, employment and trade. Thirdly, another critical element of sustainable social housing is the well-being of residents. Not just physical health but also mental health, as demonstrated during the last pandemic.

“There are two components for social housing […], below the market level [rent], and allocated through decision and rules taken by or agreed upon by local authorities [allocation]. The sustainability component is interesting […] as we consider it only as the environmental part, while doing so, we forget that sustainability is supposed to embrace the three component of environmental, social and economic. If we focus on the environmental aspects, the question […] is how we can manage to combine these three components, so we can built-renovate homes using the sources of the planet. Then […] how much we can build to meet the demands - the availability aspects. The third point is the affordability […], because everything has an impact on the ability to deliver homes at affordable price.” (J. Dijol, personal communication, November, 2023).

To this extent, I argue that environmentally sustainable social housing epitomises a multifaceted system deeply embedded within the fabric of welfare state services. It substantiates its sustainability through an intricate balance featuring economically viable and socially equitable attributes. This housing system articulates affordability in rental structures, facilitates access to natural environments, ensures proximity to pivotal services and infrastructure, implements judicious energy production and utilisation practices, underscores the imperative of decarbonisation, and intricately aligns with the tripartite foundations of sustainability—economic, social, and environmental. Significantly, this sustainable housing framework adeptly navigates societal demands while steadfastly adhering to the imperative of preserving the planet's finite resources. It looks at the new construction and considers issues such as sustainable renovation.

The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive: regulations to support or to hinder

Regulations are a vital tool in sustainable social housing provisions. It has the ability to standardise, optimise and organise the structure of the sector to deliver the intended goals. One notable example, is The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD). The EPBD is a crucial instrument to drive sustainable housing development. While regulations are traditionally seen as catalysts for progress, this narrative contends that they can also pose substantial obstacles. To contextualise this contention, it is essential to recognise the intricate links between housing construction, renovation, affordability and energy efficiency. The EPBD, alongside other directives, is a cornerstone in pursuing sustainable housing by promoting a more energy-efficient built environment. However, a critical examination of the EPBD reveals pertinent critiques. Critics argue that the occasional vagueness and lack of clarity of some of the Directive's provisions can lead to inconsistent implementation and interpretation across member states.

Furthermore, concerns have been raised that the penalties for non-compliance with the Directive are insufficient, which could reduce the effectiveness of the Directive in motivating Member States to meet energy efficiency targets. The flexibility granted to Member States in implementing the EPBD requirements has led to regulatory variations that pose challenges for cross-border businesses and hinder a harmonised approach to energy efficiency. Stakeholders argue for a stronger emphasis on renovating existing buildings in the EPBD, as the current provisions may not provide sufficient incentives for Member States to prioritise energy performance improvements to existing buildings. Additionally, critics emphasise the potential social and economic impacts, including increased costs for building owners and tenants. Balancing the Directive's energy efficiency targets with affordability and feasibility considerations is a multi-faceted challenge that should be carefully considered in pursuing a sustainable housing policy.

The way forward

The creation of sustainable social housing is not a myth or a far-reaching goal. However, it is a fact that requires comprehensive regulations and extensive co-operation between policy makers, practitioners and the public. Such collaboration enables a more holistic understanding of the challenges and opportunities associated with sustainable social housing and ensures that different factors are considered in the decision-making process. This will help to align policy with the realities on the ground and ensure that regulations are both effective and feasible. It also promotes social acceptance and buy-in for sustainable initiatives. As societal needs, technologies, and environmental considerations evolve, ongoing collaboration is important to ensure that housing strategies can be adjusted and refined to meet changing circumstances.

While natural collaboration is an optimistic notion, proactive steps, such as large-scale projects, are essential. A notable example of such collaboration is The European Affordable Housing Consortium (SHAPE-EU) project, developed and coordinated by Housing Europe. SHAPE-EU aims to support affordable and social housing providers, public authorities and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in developing effective renovation strategies and tools. This proactive approach recognises the challenges posed by the lack of policy measures, the realities of the market and the actual capacity for growth, and points a way forward in the search for sustainable and affordable housing solutions.

Acknowledgements

The time I have spent at Housing Europe has provided me with invaluable insights into social housing development. More importantly, meeting and working with dedicated and professional colleagues was truly inspirational. I have received tremendous support from all the teams and must therefore thank everyone at Housing Europe, especially Alice Pittini, Sorcha Edwards, Julien Dijol and Joao Goncalves.

Related cases

The Sutton Estate Regeneration, Chelsea

Created on 25-10-2024