Mortgage subsidisation policies in Croatia

Created on 02-10-2023 | Updated on 02-10-2023

Since 2017, Croatia implemented a new housing subsidy programme (SSK) covering up to 50% of a monthly loan annuity for the first In 2017, Croatia implemented a new housing subsidy programme (SSK) which covers up to 50% of a monthly loan annuity for the first five years of mortgages up to 100,000 EUR. Recent economic evidence claims this policy has led to an increase in house prices. This case study uses a political economy lens to contextualise this subsidy within contemporary changes in the Croatian housing system and, more broadly, in the social policy of the country. Our objective is to mobilise evidence from economics, sociology and political science to address the role of housing in the reformulation of social policy in the Croatian transition. In Croatia, state intervention in mortgage markets is not limited to macroprudential and financial regulations, but has shifted towards an understanding of mortgage markets as the main locus of housing-related social policies.

**This case study draws partially from a previously published article (Fernández & Bežovan, 2023)

Instrument

mortgage subsidy

Issued (year)

2017

Application period (years)

2017-

Scope

country (Croatia)

Target group

first-time buyers

Housing tenure

Owner

Discipline

Public policy

Object of study

Instrument

Description

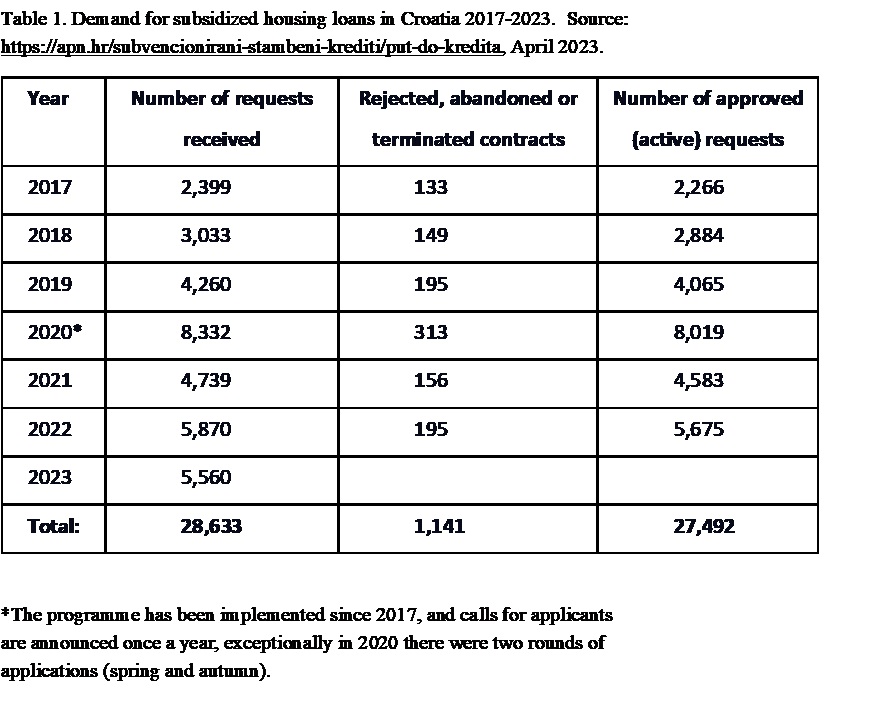

In 2017, the Croatian parliament introduced a new housing loan subsidy programme (cro. subvencioniranje stambenih kredita – SSK). Using data from 2017 to 2019, a first evaluation of the impact this subsidy has had on the housing market indicates that it has worsened housing affordability. Evidence points to the majority of the subsidies being concentrated in urbanised areas in already dynamic housing markets (Kunovac & Zilic, 2021).

Background

The socialist legacy of housing policy was hastily deconstructed during the transition of the 1990s, however it was not replaced by efficient and just housing provision. Housing privatization of a giveaway kind, mostly in terms of the right to buy and limited denationalization measures became the central reformist aspect of the Croatian housing policy transition, while adequate and lawful marketization lagged behind. In the first decade of the transition, the number of public housing units fell from 24% in 1991 to 2.6% in 2001 while homeownership level rose from 64% to 82.9% in the same period (Bežovan, 2013). In the aftermath of the Croatian War of Independence, housing measures focused on reconstruction and emergency provision for refugees and war victims. Reconstruction measures were mostly directed at households living in or returning to the so called “areas of special state care”, in other words the worse-off territories. Foreign technical assistance projects were not implemented in Croatia due to various reasons, mostly regarding clientelism, corruption and international political isolation, which at the time coincided with the process of housing deprofessionalization and the negligence of housing cooperatives as relicts of the socialist past.

Not wanting to fall back on outdated socialist practices but instead to become part of a highly developed world by means of implementing liberal housing policy, policymakers went on a path of preserving a socially sensitive demeanour of an improvised middle way policy thus shying away from extremes to satisfy the political demands of the day. In other words, all that the hybrid and experimental combination of measures achieved was the creation of a peculiar housing corporatism regime that amounted to using the state to enhance market policies in housing. Still, Croatia remained firmly within the parameters of a transitional country, in line with the South European, basically Mediterranean, housing regime which could be described as a conservative, familist model based on a high degree of homeownership and family-backed housing provision or inheritance. The housing tenure structure, housing transitions and housing careers spanning from the mid-1970s to the mid-2010s unequivocally confirm this (Rodik et al., 2019). The strong legacy of familism in housing manifests itself through acts of primary kinship is still the dominant feature of housing transactions in Croatia.

By the end of the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s, commercial housing lending, a Bausparkassen type housing savings scheme and State-Subsidized Housing Construction (POS) model were introduced as innovative instruments to modernize Croatian housing policy. The last in line was actually a government top-down programme which was implemented in 2001 and aimed to build affordable housing in large cities for the first-time buyers. Not only was it introduced on top of the speculative and unregulated housing market, but its creation and implementation were lacking in terms of necessary analysis, public discussion as well as an evaluation of available results. As time went by, other housing policy instruments were introduced to speed up the processes in the housing market. For example, the real estate transfer tax exemption (5%) for first home buyers introduced in 2003 and rent subsidies for private rental market households that lasted from 2003 to 2010. In short, the aforementioned programmes were intended for well-off middle and upper-middle class households while social housing programmes such as housing allowances, which fall under the jurisdiction of local authorities, either do not exist or are of a residual kind (Bežovan, 2019; 2018).

In these circumstances, it is difficult to build an efficient and sustainable system of social and public rental housing (Hegedus et al., 2013). The new supply subsidy measures were short-term and ineffective. Dwellings built in these programmes have been largely privatized or are under pressure to privatize, which is interpreted as a trap of the earlier privatization of the state-owned housing stock (giveaway privatization) in the early 1990s. The results of research in transition countries show that part of the younger population, who did not stand to receive family inheritance or who were less competitive in the labour market, tended to opt for long-term privately owned apartment rentals (Hegedüs et al., 2018).

Around this time, housing financialization in Croatia began to gain momentum, primarily driven by commercial housing lending. This trend continued despite the setback caused by the financial crisis and the subsequent prolonged recession in the Croatian economy. Namely, as a result of the onset of the crisis in 2009, the credit market froze and, faced with fiscal contraction, government housing supply also declined. In the midst of the economic crisis of 2010, the government started encouraging the sale of unsold flats as well as subsidizing housing loans and making state guarantees on them in 2011. With these legal measures, the state wanted to jump start stagnant activity in the credit and real estate markets, while at the same time the Socially Encouraged Rent Program (PON) enabled rental housing in POS flats with the possibility of a buyout after the expiry of the five-year contract period. From the end of 1990s to the latest period of housing loan subsidies for first-time buyers starting in 2017, housing policy measures were almost exclusively designed to support future homeowners. These resulted in serious housing market distortions and inequities.

Policy Characteristics and Analysis - (Fernández & Bežovan, 2023)

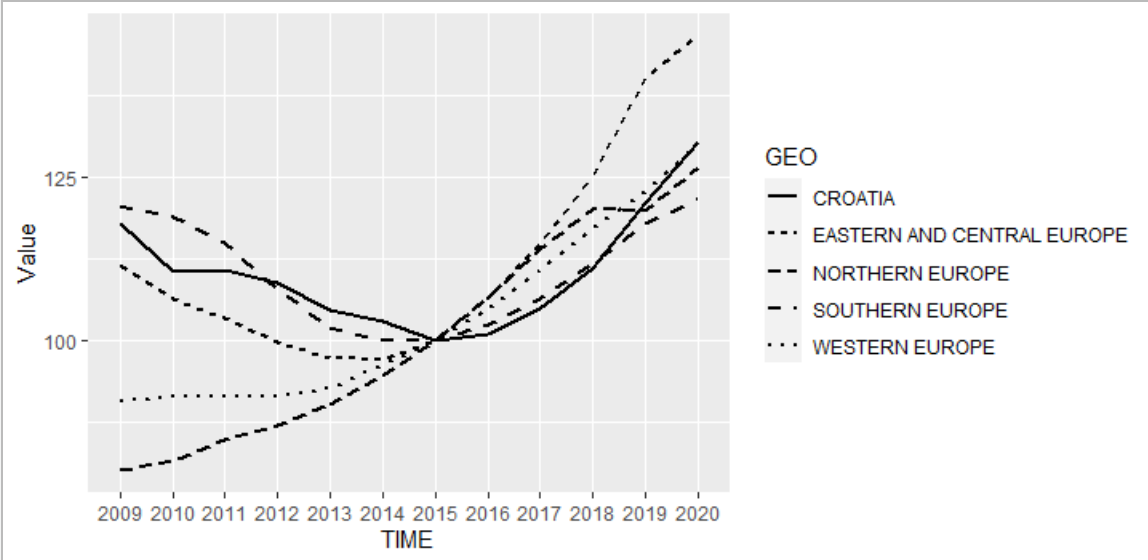

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, Croatia found itself in a deep economic crisis that resulted in a reduction in completed buildings and building permits until 2015. The collapse of the housing and stock markets reduced the financial assets of a generation of Croatian households while leaving a trail of stagnant property prices and unsold housing units. It is in the context of the early signs of recovery that the SSK was formulated. E-consultations and parliamentary debates in during the adoption of the Bill and its amendments denote the concerns raised at the time of its inception.

Critiques raised during the adoption of the Bill delve into the fact that, according to estimates, only 10% of the population were eligible for this measure and that no risk management plan had been elaborated to ensure the repayment of loans after the end of subsidised period. The regressive nature of this measure was also underlined, since income requirements for the subsidy were indirectly set by the banks’ lending criteria without any provision of advantageous rates for lower or single income households. The Bill was also criticised for the introduction of a 3% real estate transfer tax when buying a first home. Moreover, greater subsidies were proposed for the less developed parts of the country, which the government initially refused, but later accepted and amended the Bill.

According to the Bill itself, this subsidy had two aims, on the one hand to increase birth rates by providing younger couples with a home to create a family, and on the other hand to incentivize economic growth. Since its implementation in 2017, the housing loans subsidy has been managed by the Agency for Transactions and Mediation in Immovable Properties (APN). The eligibility criteria requires the applicant to be younger than 45 years old and have successfully applied for a loan with a registered bank to buy or build a property. In the call, the maximum subsidy was capped at 100.000 EUR and the maximum property price eligible was 1,500 EUR/m2. The subsidised percentage is also capped between 30 and 50% of the property value with less developed areas being eligible for higher subsidy proportions than more developed ones. Properties above this EUR/m2 threshold are still eligible but the subsidy is only applied to the proportion of the property value below this amount. The loan must last at least 15 years and the effective interest rate (EIR) for the first five years of its repayment may not exceed 3.75% per annum.

The subsidy is paid in such a way that it covers half of the monthly instalments or annuities of the first four years of loan repayment. Given that this subsidy was designed with the objective of promoting demographic growth, households who have children during the first five years of repayment receive an extension of two more years per child to their subsidy. Similarly, if a member of the household has a 50% or more disability the loan repayment period increases by one more year. The apartment shall not be rented within two years on completion of the repayment of the subsidy and the recipient must be officially registered there.

One of the main setbacks in the design of this particular policy is the eligibility criteria. In the first place, mortgage eligibility criteria are the same with or without a subsidy as credit institutions and banks require clients to satisfy their lending requirements prior to obtaining the subsidy. Secondly, subsidy eligibility is particularly lax on other dimensions as there in no income cap, the policy does not target first-time-buyers and includes older households up to the age of 45. During the discussions about the latest amendments to the Bill in 2020, the effect of this programme on the increase of housing prices were discussed, however, these concerns were ignored in the final bill. The government also rejected the suggestion to keep the measure applications open continuously throughout the year, and the suggestion that due to increased housing prices, the total loan amount would increase, along with the amount per square meter that can be subsidized.

Alignment with project research areas

This case study is highly relevant to the research areas of RE-DWELL, a transdisciplinary project focused on housing affordability. This case sheds light on the implementation and effects of the housing subsidy programme (SSK) in Croatia, which provides significant insights into the dynamics of housing affordability and social policy in the country.

Firstly, the case explores the economic evidence suggesting that the SSK subsidy has led to an increase in housing prices. This finding directly relates to the research area of housing affordability, as it highlights the potential unintended consequences of housing subsidies on the overall affordability of housing in Croatia. By examining the impacts of the subsidy on housing prices, the case provides valuable information for researchers and policymakers involved in the RE-DWELL project, enabling them to better understand the complexities of housing affordability and formulate evidence-based solutions.

Moreover, the case employs a political economy lens to contextualize the housing subsidy with respect to contemporary changes in the Croatian housing system and its broader social policy. This approach aligns with the transdisciplinary nature of the RE-DWELL project, which seeks to integrate multiple disciplines, including economics, sociology, and political science, to gain a comprehensive understanding of housing-related issues. By mobilizing evidence from these disciplines, the case offers a holistic perspective on the role of housing in the reformulation of social policy during the Croatian transition.

Furthermore, the case highlights that state intervention in mortgage markets in Croatia goes beyond macroprudential and financial regulations. Instead, it emphasizes the evolving understanding of mortgage markets as a primary locus for housing-related social policies. This observation has direct relevance to the research areas of RE-DWELL, which aim to explore innovative policy approaches and governance mechanisms to enhance housing affordability. Understanding the shifting role of mortgage markets and the interplay between housing subsidies and social policies is crucial for the project's objective of developing effective strategies for sustainable and affordable housing.

In conclusion, the examination of the housing subsidy programme in Croatia, its impacts on housing prices, and its contextualization within the housing system and social policy aligns closely with the research areas of RE-DWELL. By incorporating economic, sociological and political science perspectives, the case provides valuable insights into the dynamics of housing affordability and the reformulation of social policy in the Croatian transition. The findings and analysis presented in this case can inform and enrich the ongoing research and initiatives within the RE-DWELL project.

References

Bežovan, G. (2013). Croatia: The Social Housing Search Delayed by Postwar Reconstruction. In J. Hegedüs; M. Lux, & N. Teller (Eds.), Social Housing in Transitional Countries. (pp. 128-145). Routledge.

Bežovan, G. (2018). Croatia: Towards Formalization. In J. Hegedüs, M. Lux, & V. Horváth (Eds.), Private Rental Housing in Transition Countries: An Alternative to Owner Occupation?. (pp. 149-166). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-50710-5

Fernández, A., & Bežovan, G. (2023). The Role of Mortgage Subsidies in the Croatian Economic Growth Strategy: A Political-Economy Approach to the SSK. Critical Housing Analysis, 10(1), 50–65. https://doi.org/10.13060/23362839.2023.10.1.553

Hegedüs, J., Lux, M., & Horváth, V. (2017). Private Rental Housing in Transition Countries: An Alternative to Owner Occupation? Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-50710-5

Hegedus, J., Lux, M., & Teller, N. (Eds.). (2013). Social Housing in Transition Countries. Routledge.

Kunovac, D., & Zilic, I. (2021). The Effect Of Housing Loan Subsidies on Affordability: Evidence from Croatia. Journal of Housing Economics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2021.101808

Rodik, P., Matković, T., Pandžić, J. (2019). Stambene karijere u Hrvatskoj: od samoupravnog socijalizma do krize financijskog kapitalizma (Housing Careers in Croatia: From Self-Governing Socialism to the Crisis of Financial Capitalism). Croatian Sociological Review, 49 (3), 319-348. https://doi.org/10.5613/rzs.49.3.1