Mortgage subsidisation policies in Croatia

Created on 02-10-2023

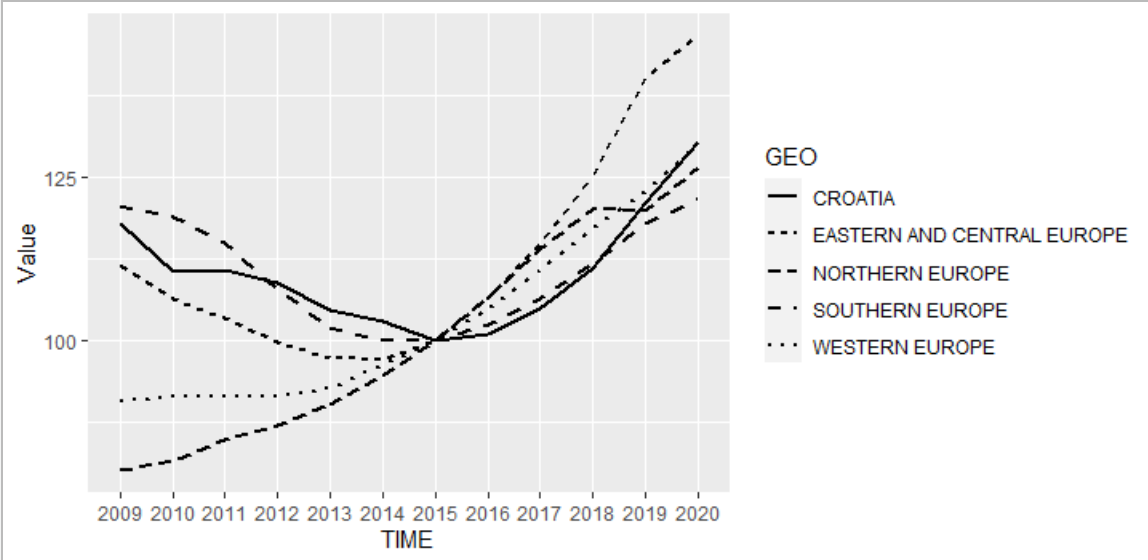

In 2017, the Croatian parliament introduced a new housing loan subsidy programme (cro. subvencioniranje stambenih kredita – SSK). Using data from 2017 to 2019, a first evaluation of the impact this subsidy has had on the housing market indicates that it has worsened housing affordability. Evidence points to the majority of the subsidies being concentrated in urbanised areas in already dynamic housing markets (Kunovac & Zilic, 2021).

Background

The socialist legacy of housing policy was hastily deconstructed during the transition of the 1990s, however it was not replaced by efficient and just housing provision. Housing privatization of a giveaway kind, mostly in terms of the right to buy and limited denationalization measures became the central reformist aspect of the Croatian housing policy transition, while adequate and lawful marketization lagged behind. In the first decade of the transition, the number of public housing units fell from 24% in 1991 to 2.6% in 2001 while homeownership level rose from 64% to 82.9% in the same period (Bežovan, 2013). In the aftermath of the Croatian War of Independence, housing measures focused on reconstruction and emergency provision for refugees and war victims. Reconstruction measures were mostly directed at households living in or returning to the so called “areas of special state care”, in other words the worse-off territories. Foreign technical assistance projects were not implemented in Croatia due to various reasons, mostly regarding clientelism, corruption and international political isolation, which at the time coincided with the process of housing deprofessionalization and the negligence of housing cooperatives as relicts of the socialist past.

Not wanting to fall back on outdated socialist practices but instead to become part of a highly developed world by means of implementing liberal housing policy, policymakers went on a path of preserving a socially sensitive demeanour of an improvised middle way policy thus shying away from extremes to satisfy the political demands of the day. In other words, all that the hybrid and experimental combination of measures achieved was the creation of a peculiar housing corporatism regime that amounted to using the state to enhance market policies in housing. Still, Croatia remained firmly within the parameters of a transitional country, in line with the South European, basically Mediterranean, housing regime which could be described as a conservative, familist model based on a high degree of homeownership and family-backed housing provision or inheritance. The housing tenure structure, housing transitions and housing careers spanning from the mid-1970s to the mid-2010s unequivocally confirm this (Rodik et al., 2019). The strong legacy of familism in housing manifests itself through acts of primary kinship is still the dominant feature of housing transactions in Croatia.

By the end of the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s, commercial housing lending, a Bausparkassen type housing savings scheme and State-Subsidized Housing Construction (POS) model were introduced as innovative instruments to modernize Croatian housing policy. The last in line was actually a government top-down programme which was implemented in 2001 and aimed to build affordable housing in large cities for the first-time buyers. Not only was it introduced on top of the speculative and unregulated housing market, but its creation and implementation were lacking in terms of necessary analysis, public discussion as well as an evaluation of available results. As time went by, other housing policy instruments were introduced to speed up the processes in the housing market. For example, the real estate transfer tax exemption (5%) for first home buyers introduced in 2003 and rent subsidies for private rental market households that lasted from 2003 to 2010. In short, the aforementioned programmes were intended for well-off middle and upper-middle class households while social housing programmes such as housing allowances, which fall under the jurisdiction of local authorities, either do not exist or are of a residual kind (Bežovan, 2019; 2018).

In these circumstances, it is difficult to build an efficient and sustainable system of social and public rental housing (Hegedus et al., 2013). The new supply subsidy measures were short-term and ineffective. Dwellings built in these programmes have been largely privatized or are under pressure to privatize, which is interpreted as a trap of the earlier privatization of the state-owned housing stock (giveaway privatization) in the early 1990s. The results of research in transition countries show that part of the younger population, who did not stand to receive family inheritance or who were less competitive in the labour market, tended to opt for long-term privately owned apartment rentals (Hegedüs et al., 2018).

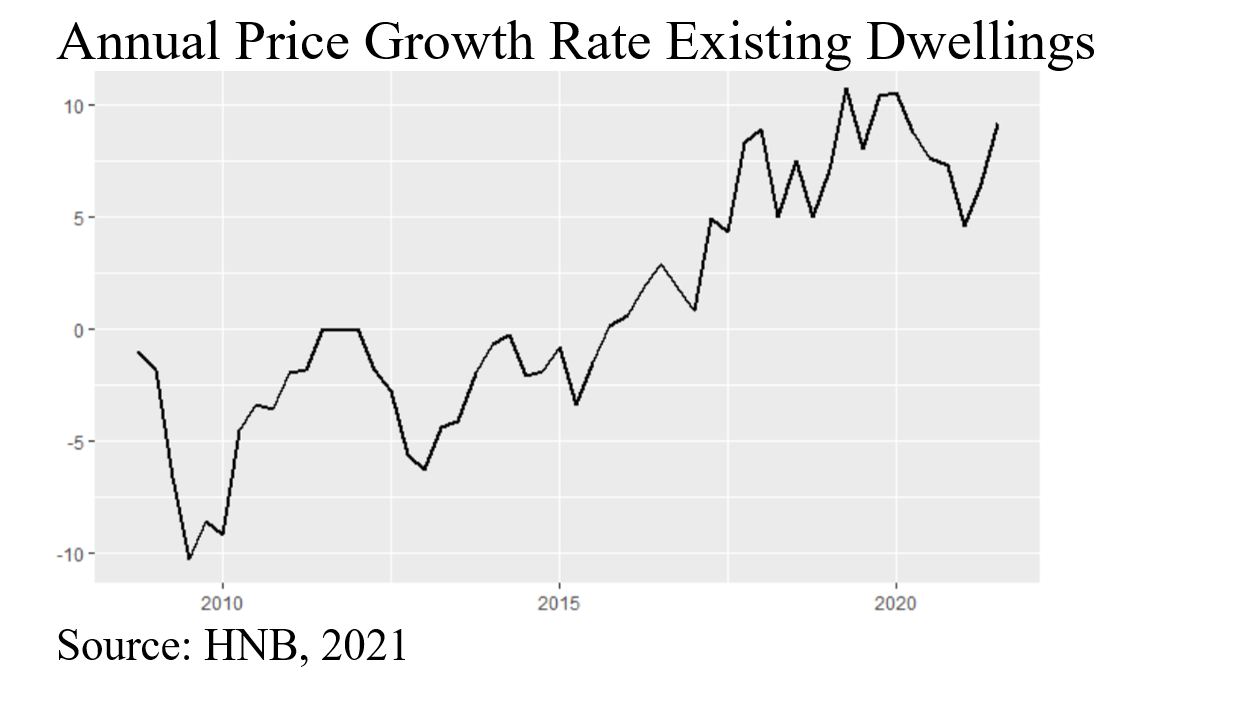

Around this time, housing financialization in Croatia began to gain momentum, primarily driven by commercial housing lending. This trend continued despite the setback caused by the financial crisis and the subsequent prolonged recession in the Croatian economy. Namely, as a result of the onset of the crisis in 2009, the credit market froze and, faced with fiscal contraction, government housing supply also declined. In the midst of the economic crisis of 2010, the government started encouraging the sale of unsold flats as well as subsidizing housing loans and making state guarantees on them in 2011. With these legal measures, the state wanted to jump start stagnant activity in the credit and real estate markets, while at the same time the Socially Encouraged Rent Program (PON) enabled rental housing in POS flats with the possibility of a buyout after the expiry of the five-year contract period. From the end of 1990s to the latest period of housing loan subsidies for first-time buyers starting in 2017, housing policy measures were almost exclusively designed to support future homeowners. These resulted in serious housing market distortions and inequities.

Policy Characteristics and Analysis - (Fernández & Bežovan, 2023)

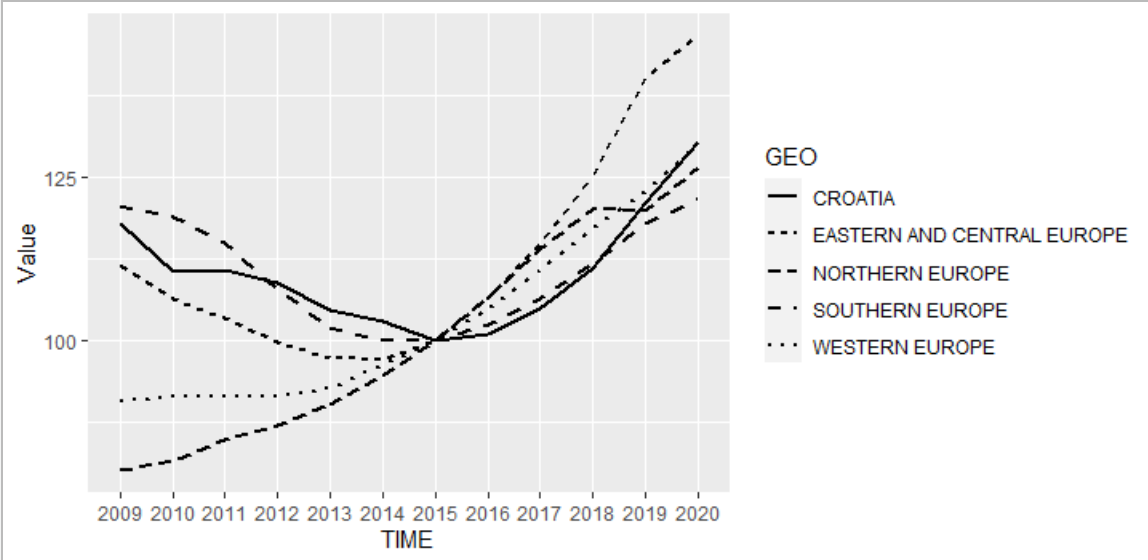

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, Croatia found itself in a deep economic crisis that resulted in a reduction in completed buildings and building permits until 2015. The collapse of the housing and stock markets reduced the financial assets of a generation of Croatian households while leaving a trail of stagnant property prices and unsold housing units. It is in the context of the early signs of recovery that the SSK was formulated. E-consultations and parliamentary debates in during the adoption of the Bill and its amendments denote the concerns raised at the time of its inception.

Critiques raised during the adoption of the Bill delve into the fact that, according to estimates, only 10% of the population were eligible for this measure and that no risk management plan had been elaborated to ensure the repayment of loans after the end of subsidised period. The regressive nature of this measure was also underlined, since income requirements for the subsidy were indirectly set by the banks’ lending criteria without any provision of advantageous rates for lower or single income households. The Bill was also criticised for the introduction of a 3% real estate transfer tax when buying a first home. Moreover, greater subsidies were proposed for the less developed parts of the country, which the government initially refused, but later accepted and amended the Bill.

According to the Bill itself, this subsidy had two aims, on the one hand to increase birth rates by providing younger couples with a home to create a family, and on the other hand to incentivize economic growth. Since its implementation in 2017, the housing loans subsidy has been managed by the Agency for Transactions and Mediation in Immovable Properties (APN). The eligibility criteria requires the applicant to be younger than 45 years old and have successfully applied for a loan with a registered bank to buy or build a property. In the call, the maximum subsidy was capped at 100.000 EUR and the maximum property price eligible was 1,500 EUR/m2. The subsidised percentage is also capped between 30 and 50% of the property value with less developed areas being eligible for higher subsidy proportions than more developed ones. Properties above this EUR/m2 threshold are still eligible but the subsidy is only applied to the proportion of the property value below this amount. The loan must last at least 15 years and the effective interest rate (EIR) for the first five years of its repayment may not exceed 3.75% per annum.

The subsidy is paid in such a way that it covers half of the monthly instalments or annuities of the first four years of loan repayment. Given that this subsidy was designed with the objective of promoting demographic growth, households who have children during the first five years of repayment receive an extension of two more years per child to their subsidy. Similarly, if a member of the household has a 50% or more disability the loan repayment period increases by one more year. The apartment shall not be rented within two years on completion of the repayment of the subsidy and the recipient must be officially registered there.

One of the main setbacks in the design of this particular policy is the eligibility criteria. In the first place, mortgage eligibility criteria are the same with or without a subsidy as credit institutions and banks require clients to satisfy their lending requirements prior to obtaining the subsidy. Secondly, subsidy eligibility is particularly lax on other dimensions as there in no income cap, the policy does not target first-time-buyers and includes older households up to the age of 45. During the discussions about the latest amendments to the Bill in 2020, the effect of this programme on the increase of housing prices were discussed, however, these concerns were ignored in the final bill. The government also rejected the suggestion to keep the measure applications open continuously throughout the year, and the suggestion that due to increased housing prices, the total loan amount would increase, along with the amount per square meter that can be subsidized.

A.Fernandez (ESR12)

Read more

->

ESG finance and social housing decarbonisation

Created on 05-02-2024

Over the last decades, ESG debt issuance, through green, social or sustainability-linked loans and bonds has become increasingly common. Financial markets have hailed the adoption of ESG indicators as a tool to align capital investments with environmental and social goals, such as the decarbonisation of the social housing stock. According to the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), the green debt market has experienced a 50% growth over the last five years (CBI, 2021). However, the lack of clearly established indicators and objectives has tainted the growth of green finance with a series of high-level scandals and accusations of green-washing, unjustified claims of a company’s green credentials. For example, a fraud investigation by German prosecutors into Deutsche Bank’s asset manager, DWS, has found that ESG factors were not taken into account in a large number of investments despite this being stated in the fund’s prospectus (Reuters, 2022).

To curb greenwashing and improve transparency and accountability in green investments, the EU has embarked on an ambitious legislative agenda. This includes the first classification of environmentally sustainable economic activities: the EU Green Taxonomy (Regulation 2020/852). The Taxonomy is directly linked to the European Commission’s decarbonisation strategy, the Renovation Wave (COM (2020) 662), which relies on a combination of private and public finance to secure the investment needed for the decarbonisation of social housing.

Energy efficiency targets have become increasingly stringent as the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) and its successive recasts (COM(2021)) have been incorporated into national legislation; see for example the French Loi Climate et Resilience (2021-1104, 2021). Consequently, capital expenses for SHOs are set to increase considerably. For example, in the Netherlands, according to a Housing Europe (2020) report, attaining the 2035 energy efficiency targets set by the Dutch government will cost €116bn.

Sustainable finance legislation constitutes an expansion of the financial measures implemented by the EU in recent decades to incentivise energy efficiency standards as well as renovations in the built environment. For more detail on prior EU policies, see Economidou et al. (2020) and Bertoldi et al. (2021). The increased connections between finance and energy performance raise specific questions regarding SHOs’ access to capital markets in light of the shift toward ESG.

The rapidly expanding finance literature on green bonds draws from econometric models to explore the links between investors’ preferences and yields (Fama & French, 2007). This body of literature on asset pricing relies on the introduction of non-pecuniary preferences in investors’ utility functions together with returns and risks to explain fluctuations in the equilibrium price of capital. Drawing from a comparison between green and conventional bonds, Hachenberg and Schiereck (2018) find evidence of the former being priced at a premium. Similarly, Zerbib (2019) also shows a low but significant negative yield premium for green bonds resulting from both investors’ environmental preferences and lower risk levels. The European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (Fatica & Panzica, 2021) documents the dependency of premiums on the issuer with significant estimates for supranational institutions and corporations, but not for financial institutions. While these econometric approaches offer relevant insight into the pricing of green bonds and the incentives for issuers and investors, they do not account for the institutional particularities of social housing, a highly regulated sector usually covered by varying forms of state guarantees and subsidisation (Lawson, 2013).

ESG-labelled debt instruments & Related Legislation

Throughout the last two decades, the term ESG finance has evolved to include a large number of financial vehicles of which green bonds have become the most popular (Cortellini & Panetta, 2021). In the social housing sector, ESG comprises a broad array of tools from sustainability-linked loans to less conventional forms of finance such as carbon credits. When it comes to bonds, there is a wide variation in the sustainability credentials among the different types. Broadly speaking, green and social bonds are issued under specific ‘use of proceeds’, which means the funds raised must be used to finance projects producing clear environmental or social benefits. The issuance of these types of bonds requires a sustainable finance framework, which is usually assessed by a third party emitting an opinion on its robustness.

Sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) are an alternative to ‘use of proceeds’. Funds raised in this manner are not earmarked for sustainable projects, but can be used for general purposes. SLBs are linked to the attainment of certain company-wide Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), for example an average Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of “C” in an SHO’s housing stock. These indicators and objectives usually result in a price premium for Sustainable Bonds, or a rebate in interest rates in the case of SLBs or sustainability-linked loans (SLLs) (Cortellini & Panetta, 2021).

While there are international standards for the categorisation of green projects such as the Green Bond Principle or the Climate Bonds Strategy, strict adherence is optional and there are few legally-binding requirements resulting in a large divergence in reporting practices and external auditing. To solve these issues and prevent greenwashing, the EU has been the first regulator to embark on the formulation of a legal framework for green finance through a series of acts targeting the labelling of economic activities, investors, corporations and financial vehicles.

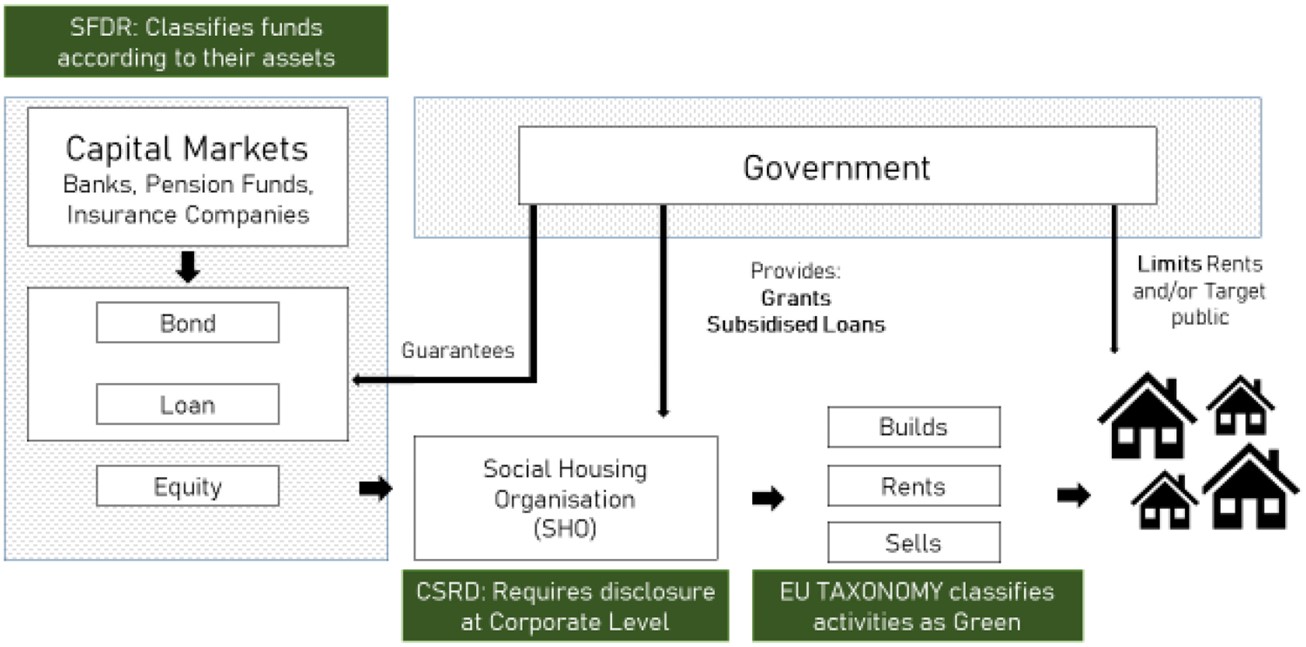

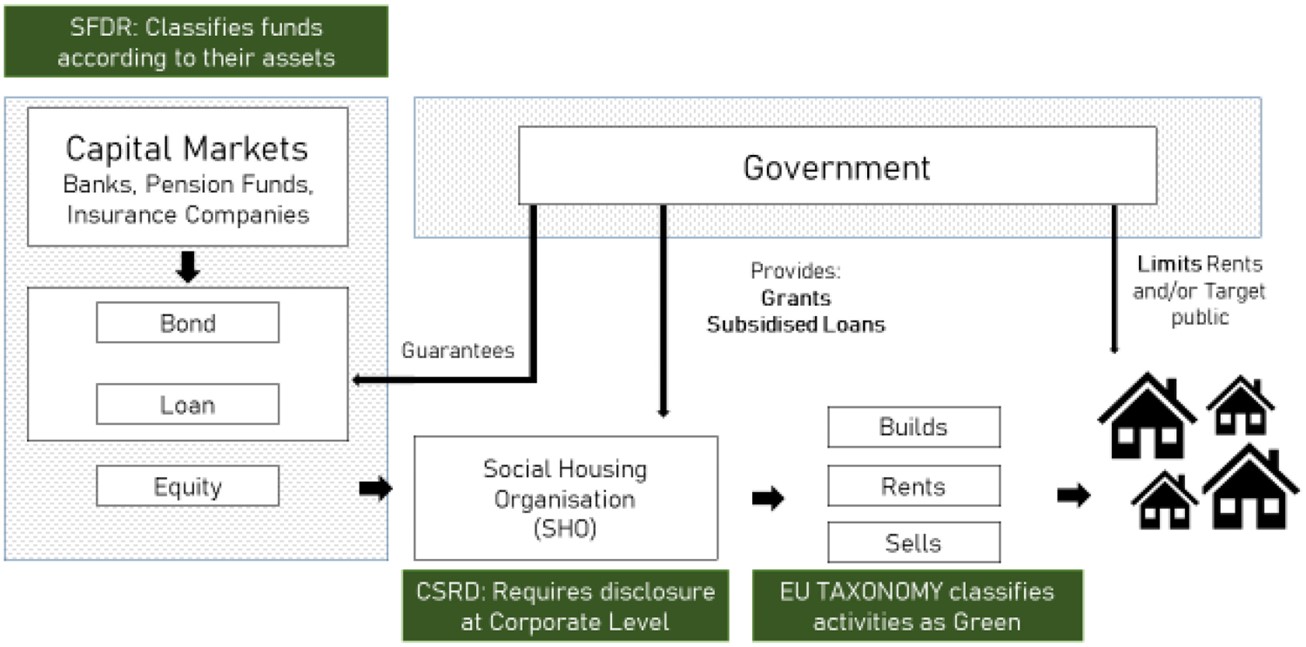

First, the EU Green Taxonomy (Regulation (EU) 2020/852) is the cornerstone of this new legislation since it classifies economic activities attending to their alignment with the objectives set in the European Green Deal (EGD). When it comes to housing, the EU Taxonomy requires specific energy efficiency levels for a project to be deemed ‘taxonomy aligned’. Second, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) (Regulation (EU) 2019/2088) mandates ESG reporting on funds, which tend to consist of exchange-traded collections of real assets, bonds or stocks. Funds are required to self-classify under article 6 with no sustainability scope, ‘light green’ article 8 which incorporates some sustainability elements, and article 9 ‘dark green’ for funds only investing in sustainability objectives. Under the SFDR, which came into effect in January 2023, fund managers are required to report the proportion of energy inefficient real estate assets as calculated by a specific formula taking into account the proportion of ‘nearly zero-energy building’, ‘primary energy demand’ and ‘energy performance certificate’ (Conrads, 2022). Third, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)(COM(2021) 189) increases disclosure requirements for corporations along Taxonomy lines. This legislation, which came into effect in 2023, will be progressively rolled out starting from larger and listed companies and expanding to a majority of companies this decade. Provisions have been made for charities and non-profits to be exempt. However, one of the key consequences of disclosure requirements over funds through the SFDR is its waterfall effect; that is the imposition of indirect reporting requirements as investors pass-on their reporting responsibilities to their borrowers. Fourth, the proposed EU Green Bonds Standards (EU-GBS) COM(2021) 391 aims to gear bond proceedings toward Taxonomy-aligned projects and increase transparency through detailed reporting and external reviewing by auditors certified by the European Security Markets Authorities (ESMA). The main objectives of these legislative changes is to create additionality, that is, steer new finance into green activities (see Figure 1).

While this new legislation is poised to increase accountability and transparency, it also aims to encourage a better management of environmental risks. According to a recent report on banking supervision by the European Central Bank (ECB), real estate is one of the major sources of risk exposure for the financial sector (ECB, 2022). This includes both physical risks, those resulting from flooding or drought and, more relevant in this case, transitional risks, that is those derived from changes in legislation such as the EPBD and transposing national legislation. The ECB points to the need for a better understanding of risk transmission channels from real estate portfolios into the financial sector through enhanced data collection and better assessments of energy efficiency, renovation costs and investing capacity. At its most extreme, non-compliance with EU regulations could result in premature devaluation and stranded assets (ECB, 2022).

In short, the introduction of reporting and oversight mechanisms connects legislation on housing’s built fabric, namely the EPBD, to financial circuits. On the one hand, the EU has been strengthening its requirements vis-à-vis energy efficiency over the last decades. The Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) suggested the introduction of Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) by Member States (Economidou et al., 2020), a rationale followed by France and the Netherlands for certain segments of the housing stock. Currently, policy-makers are debating on whether the EPBD’s recast (COM/2021/802) should incorporate MEPS and make decarbonisation an obligation for SHOs across the EU. On the other hand, legislation on green finance aims to produce incentives and oversight over investments in energy efficient renovation and new build, mobilising the private sector to cater to green projects (Renovation Wave (COM(2020) 662)).

A.Fernandez (ESR12)

Read more

->

Housing retrofit subsidies in the Netherlands

Created on 20-11-2024

In Europe, the push for energy-efficient housing has led to widespread use of financial incentives such as grants, loans, and tax rebates to encourage homeowners to undertake retrofits. These measures aim to reduce energy consumption and improve the environmental performance of residential buildings. Governments across the continent have adopted various programs to support these efforts, offering significant financial aid to make energy-saving improvements more accessible to homeowners. In addition to subsidies, some countries implement energy taxes to further promote efficiency and fund sustainability initiatives. At the European Union level, comprehensive strategies are being developed to enhance the energy efficiency of buildings, including proposals for new regulatory frameworks and financial incentives. This multi-faceted approach reflects a growing recognition of the importance of sustainable housing in achieving broader environmental and economic goals.

Subsidisation of housing retrofit, through grants and loans, as well as tax rebates are commonly used across Europe to incentivise the energy-efficient retrofit of the housing stock (Castellazzi et al., 2019). Following this trend, the Dutch government has put in place a series of grants and subsidised loans to incentivise retrofit. First, the “Subsidie Energiebesparing Eigen Huis” is a grant programme covering up to 50% of retrofit costs when at least two energy-saving measures improving EPC levels have been implemented. Dutch homeowners can also apply for the Investment Grant for Sustainable Energy Savings (ISDE) in the case of single measures such as solar boilers or heat pumps (Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy, 2019). Since 2022, 0% interest loans are also available to low-income households from the National Heat Fund.

On the stick side of retrofit incentivation, the Netherlands implements a regressive form of carbon taxation on individual households (Maier & Ricci, 2024). Research by the Dutch National Bank has also alluded to the strong impact of energy taxation on lower incomes and the inelasticity of energy consumption. Havlinova et al. (2022) have found that the introduction of stronger forms of energy taxation in heated energy markets can impinge on lower incomes resulting in regressive distributional impacts. At the EU level, the Renovation Wave is actively promoting this approach to housing retrofit through its proposal to include buildings in the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) together with the implementation of retrofit subsidies(2003/87/EC). As a result, while owner-occupied housing is undertaxed, the tax burden on energy consumption at the household level is poised to increase.

Retrofit subsidies usually come to join fiscal systems favouring owner occupation. These forms of direct subsidisation of housing retrofit coalesce with increases in the fiscal burden on energy consumption. According to Haffner & Heylen (2011), the housing taxation structure favours owner-occupation with a mortgage through large deductions in income tax. In the Netherlands, imputed rent, the main form of housing taxation is calculated on the basis of a notional rent value and then added onto box 1 which comprises labour income. All other income from investments is taxed under box 3 at a different rate. Haffner & Heylen (2011) have analysed the lack of tax neutrality in this system and propose to include the taxation of housing assets under box 3 as a tax-neutral benchmark. In the context of housing retrofit, the favourable fiscal treatment of homeownership comes to join generous subsidies for owner-occupied housing retrofit with no maximum income threshold offered by the Dutch government. A green tax is a viable alternative to incentivise retrofit in a more progressive manner.

The Dutch approach to incentivising housing retrofits exemplifies a broader European commitment to enhancing energy efficiency through a combination of financial incentives and regulatory measures. While generous subsidies and tax incentives significantly benefit homeowners, particularly those with mortgages, the regressive nature of energy taxation presents challenges for lower-income households.

Research indicates that increased energy taxation disproportionately impacts these households, underscoring the need for more progressive solutions. The EU’s Retrofit Wave, along with the proposed inclusion of buildings in the ETS, reflects an ongoing effort to balance these measures. In the context of housing retrofits, a shift towards green taxes could provide a more equitable framework, ensuring that the financial burden and benefits of energy-efficient improvements are more evenly distributed across different income groups.

(This text is an excerpt from : Fernández, A., Haffner, M. & Elsinga, M. Subsidies or green taxes? Evaluating the distributional effects of housing renovation policies among Dutch households. J Hous and the Built Environ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-024-10118-5 )

M.Elsinga (Supervisor), M.Haffner (Supervisor), A.Fernandez (ESR12)

Read more

->