Broadwater Farm Urban Design Framework

Created on 26-07-2024

The Broadwater Farm Estate

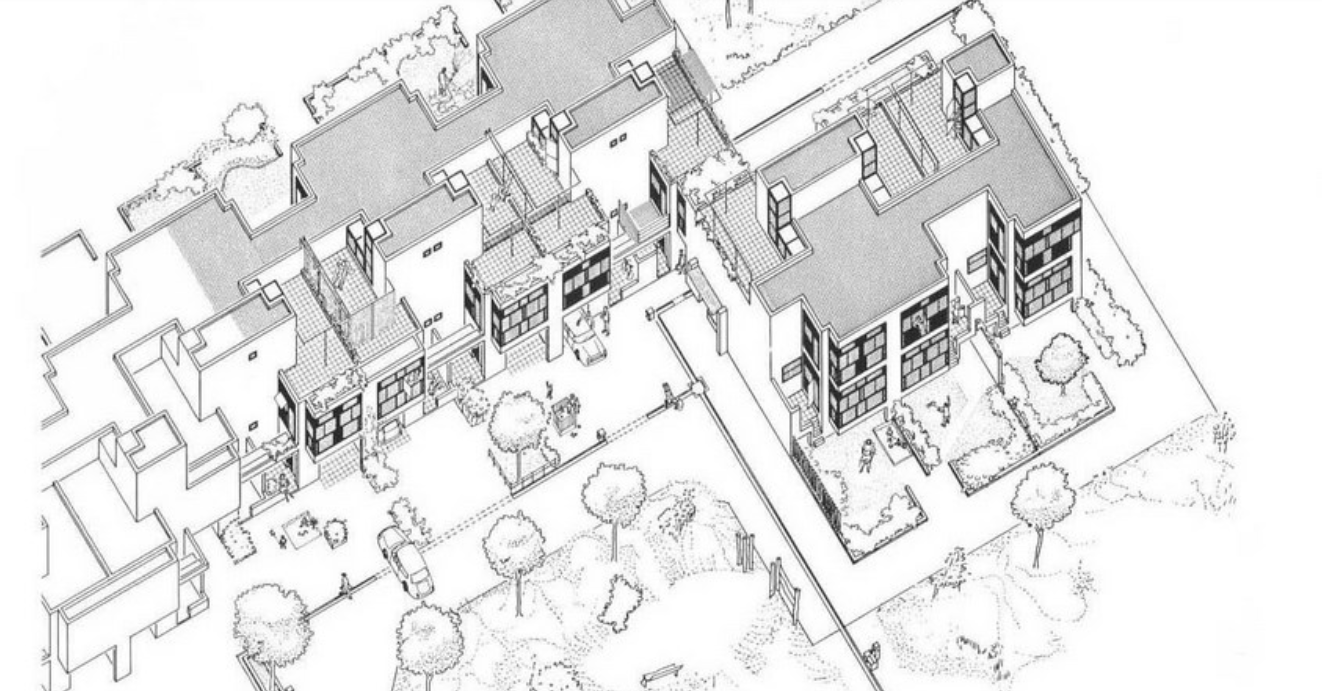

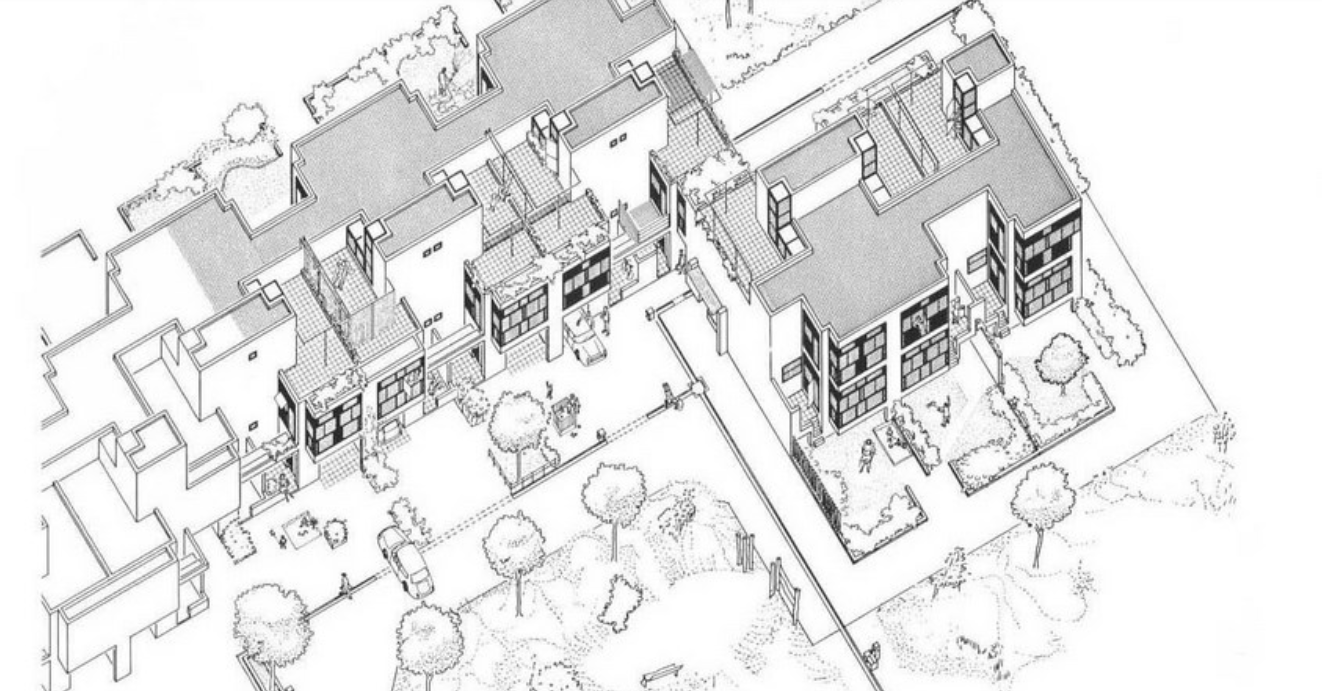

The estate, built in the full swing of modernism, is a paragon of the movement’s defining characteristics. The building density is notably high compared to the surrounding single-family terraced houses. There is a clear separation between vehicles and pedestrians, with platforms and deck accesses. The ensemble comprises twelve high-rise precast concrete blocks and towers, which extend over a public-owned site of 18 hectares, which is unusually large by today’s standards. Facilities were also provided for residents, offering them the essential amenities. Upon completion in the early 1970s, the estate comprised 1,063 flats and was home to between 3,000 and 4,000 residents.

As was the case with numerous other modernist housing estates across the country, Broadwater Farm was significantly affected by the seminal work of Alice Coleman, Utopia on Trial (1985) on the concept of “defensible space”. Proponents of this theory posited that design had a deterministic impact on crime rates and social malaise in low-income urban communities. Although Coleman's study faced harsh criticism from academics for its questionable methodology and oversimplification of complex social problems (Cozens & Hillier, 2012; Lees & Warwick, 2022), her recommendations led to the implementation of a multi-million-pound government-funded programme for remedial works in thousands of social housing blocks nationwide; known as the DICE (Design Improvement Controlled Experiment) project. Broadwater Farm was targeted by the programme after it attracted considerable attention following the serious riots that occurred at the estate in 1985 (Stoddard, 2011). A number of initiatives were undertaken with the objective of regenerating and improving the quality of the built environment, with the earliest works beginning in 1981. Under the DICE project, a significant number of the overpass decks that connected the estate on the first floor were demolished on the grounds that they were conducive to the formation of poorly lit and isolated areas that were facilitating criminal activity and anti-social behaviour (Severs, 2010).

In the wake of the Grenfell Tower tragedy, new fire safety regulations and inspections have been introduced, resulting in two blocks of flats being deemed unfit for habitation (BBC, 2022). The Large Panel System (LPS), which was commonly used in the 1960s, has been identified as the primary cause for the demolition of the Tangmere and Northolt blocks due to the significant risk of collapse in the event of a fire. These essential repairs will be part of the largest refurbishment project ever undertaken in the estate. It will comprise a combination of retrofitting, redevelopment and infill, resulting in an increase in the number of housing units and a significant enhancement of the urban layout and public spaces across its 83,000 sq. m.

The Urban Design Framework (UDF) is a comprehensive document that sets out a series of actionable and tangible improvements for the estate. Produced by Karakusevic Carson Architects (2022) and commissioned by the Haringey Borough Council, the UDF serves as a masterplan for the ongoing regeneration of the estate. This document is the result of an extensive stakeholder involvement process. It proposes a series of five urban strategies that, taken together, provide a blueprint for holistic regeneration. These strategies account for the short, medium and long-term development of both the estate and its community.

Given the substantial size of the complex, the scale of the surrounding neighbourhood, and the intricate web of relationships within it, long-term planning holds significant importance. These aspects were emphasised through the proposed interventions that enhance the connections between the dwellings and the urban context. The impact of the estate on the surrounding area and the need for a cohesive urban landscape are addressed through designs that integrate the estate into the city fabric, rather than isolating it. The improvement plan includes the construction of new residential units through the redevelopment of the blocks earmarked for demolition and the refurbishment of the remaining blocks. The architectural firm has developed a "bank of projects," a comprehensive repository of proposed interventions arising from engagement with the community as well as a site analysis, which is organised around five core principles: streets, open spaces, ground floors, character, and homes.

Resident engagement

The inhabitants were actively involved in the creation of the UDF. A series of community engagement events, held between 2020 and 2021, provided a platform to gather the voices of residents and enabled planners to better understand their aspirations and needs, identify the key improvements required, and initiate the design process that would incorporate their views into the masterplan. This process was complemented by the establishment of the Community Design Group (CDG), formed by residents and community members who not only expressed a desire, but also demonstrated the capacity, to assume a more active role in the design process. In addition, the council has set up a website that documents and displays the schedule, events, latest news and updates on the ongoing regeneration process. This website provides comprehensive information for residents, the general public, and any interested parties seeking to gain insight into the current status of Broadwater Farm.

Placemaking strategy

In contrast to pervasive narratives about the flawed design of council estates, the spatial qualities and existing sense of belonging within the community were identified as the starting points for the placemaking strategy. The original configuration of the estate was conceived around community facilities and courtyards, which have been retained, augmented, formalised, and linked by a circuit of pedestrian and cycle paths. The deficiencies of the original design, such as the anonymous and segregated ground floor, have been addressed by establishing a network of public spaces that prioritise human scale and facilitate movement throughout the estate. These new public spaces facilitate social interaction, providing areas of activity complemented by indoor amenities and spaces for local retailers. In this way, the ground level becomes an anchor for diverse activities aimed at enhancing the sense of security.

The masterplan revolves around five principles which in turn incorporate a series of strategies:

1. Safe and Healthy Streets: The improved design shifts away from 'streets in the sky' to enhance street accessibility. It promotes intermodal transport with a new bus route into the estate and the addition of cycle lanes. The road network within the estate has been simplified to be more efficient and encourage walking. A "green" street connects key community facilities and green spaces. Overall wayfinding is enhanced through better street lighting, improved block entrances, and designated car-free areas. Part and parcel of reactivating the ground floor is creating opportunities for new activities through a redesign aimed at more efficient parking solutions to meet current needs.

2. Welcoming + Inclusive Open Spaces: Although the estate features several courtyards and open areas, residents have expressed a feeling of being in a “concrete jungle”, as noted in the community brief. The proposed improvements focused on enhancing the existing courtyards to ensure accessibility and facilitate various activities. In addition, a new community park is planned at the heart of the estate as part of the redeveloped area, designed to be a versatile and welcoming space for current and future residents alike. A hierarchy of shared and public spaces has been redesigned to create a seamless transition into and out of the estate. This seamless and unified experience of the public realm is enabled by specific elements such as play areas and seating that allow people of all ages to socialise and interact in an informal yet purposeful manner.

Workshops were conducted with specific population groups, including young women and girls or older residents, to ensure that the future estate will be as inclusive as possible. Key topics such as perceived safety in the communal areas, activities and sports facilities, as well as overall design considerations, were discussed during these sessions.

3. Ground Floors with Activity: A significant design flaw in the existing estate was the poorly lit areas adjacent to the garages that dominated the ground floor of the blocks — a common design feature in residential architecture of the time. Residents involved in the process pointed out the importance of increasing the sense of security when moving around these areas. A street-based design that activates the ground floor by enabling a greater variety of activities was central to the strategy. Alongside a clearer street layout and improved block entrances, bike racks, bin storage, and opportunities for non-residential and community uses were proposed to benefit both residents and the wider community. By repurposing areas previously used mainly for car parking into active spaces and by enhancing frontages with residential, commercial or community spaces, clear thresholds and boundaries are created to promote permeability and smooth transitions. Community facilities and local businesses are strategically located at corners and key activity nodes, facilitating passive surveillance and overlooking the public realm. The choice of materials also contributes to opening up the ground level; glazed lobbies and entrances connect indoor communal areas with adjacent outdoor spaces visually. Similarly, secondary entrances to existing blocks will be used to balance their function and prevent the creation of hidden or less frequented areas. Improved public lighting, new signage and a control system complement these strategies.

4. Broadwater Character & Scale: The architectural style known as Brutalism played a significant role in popularising the 'problem estate' narrative in Britain. This style was embraced by many of the country's modernist architects, leading to its prevalence in the social housing built during that period. Characterised by the predominant use of concrete, this style was celebrated by critic and advocate Reyner Banham for its memorable image, a clear exhibition of structure and honest expression of the material (Boughton, 2018). The monumentality and stark aesthetics of Brutalism provided an ideal setting for experimentation in the vast estates that were built during the latter half of the 20th century. These characteristics are evident in the design of Broadwater Farm.

Broadwater’s design framework acknowledges the latent potential of the existing architecture while addressing issues of materiality, building height, the links and spatial relationships between the infilled and redeveloped areas and the connection between the estate and its surroundings. The boundaries of the estate were revised to address the issue of it being perceived as an isolated entity, which was a common problem with many modernist estates. This was due to the fact that they were often of a particular size and density, which set them apart from their neighbours. In order to create a seamless transition with the surroundings, clear entrances to the estate are proposed, new materials are used that better match those of the vicinity, and a massing strategy is employed to avoid abrupt transitions in building heights.

The character of the estate was approached in a manner reminiscent of Kevin Lynch’s (1964) five elements of the city —paths, edges, districts, nodes and landmarks—, with particular emphasis on their importance in establishing a sense of place and enhancing the legibility of the urban environment. The proposal has engaged in a meticulous study of the local context, re-signifying existing elements such as the Kenley Tower, which has been retained as the tallest mass in the ensemble, in order to maintain its landmark character.

5. Good Quality Homes: The new blocks, arranged in courtyards that reflect the existing pattern of the estate, will replace the Tangmere and Northolt blocks. They will occupy a privileged position at the heart of the estate and offer an opportunity to transform the overall look of the scheme. These new blocks, complemented by infill development on nearby sites, will result in the creation of 294 new residential units, representing a net increase of 85 homes. The new dwellings, comprising three and four-bedroom family homes, will be managed by the council and rented out at social rates. A significant proportion of residents who participated in the public consultation highlighted the necessity for larger and more spacious accommodation, particularly for large families. In response to these demands, the design of the new flats incorporates larger and more flexible spaces as a key feature. Those who previously resided in the demolished blocks will be given priority for the new homes.

Furthermore, the introduction of new parks, public spaces, workspaces and a new well-being hub, which will house a doctor's surgery and other services, will help create a more active and dynamic ground floor, with activities that enhance the sense of place and welcome pedestrians. The architects have conducted an analysis of potential infill solutions to activate the ground floor, including the addition of one-bedroom flats that fit into the structural grid of the existing blocks. This in turn addresses the need to create a community that includes people of all ages and family types.

Management & Maintenance

The UDF exemplifies how regeneration projects can address current needs while allowing for future adaptations. This people-centred project fosters a sense of ownership through participation, which is crucial for the sustainability of the intervention. Stewardship is key, especially for the new collective spaces being created. Instead of a deterministic design approach, the framework considers what types of spaces can enhance the overall quality of life. It integrates social, economic, and environmental aspects that define the living and working experience in the area. These considerations are captured in the “Strategy for a Sustainable Neighbourhood.”

The bank of projects is a repository of proposed interventions within the project, illustrating the considerable interest in the long-term effects of the regeneration project and the substantial potential for future development. This section of the framework underscores the necessity for the formulation of a phased, structured and comprehensive planning and delivery strategy that allows for flexibility and input from existing and future residents. Consequently, management and maintenance are regarded as integral aspects of the design, alongside other tangible elements of the built environment.

With an approach strongly focused on creating social value and reducing the disruptive effects of regeneration. The architects have worked with the community to develop a masterplan that emphasises the use of existing assets, minimises demolition and establishes a hierarchy of priorities to maximise the positive impact in the long term.

L.Ricaurte (ESR15)

Read more

->

85 Social Housing Units in Cornellà

Created on 26-07-2024

An economic, social and environmental challenge

The architects Marta Peris and José Manuel Toral (P+T) faced the task of developing a proposal for collective housing on a site with social, economic, and environmental challenges. This social housing building won through an architectural competition organised by IMPSOL, a public body responsible for providing affordable housing in the metropolitan area of Barcelona. The block, located in the working-class neighbourhood of Sant Ildefons in Cornellà del Llobregat where the income per capita is €11,550 per year, was constructed on the site of the old Cinema Pisa. Although the cinema had closed down in 2012, the area remained a pivotal point for the community, so the social impact of the new building on the urban fabric and the existing community was of paramount importance.

The competition was won in 2017 and the housing was constructed between 2018 and 2020. The building, comprised of 85 social housing dwellings, covers a surface of 10,000m2 distributed in five floors. Adhering to a stringent budget based on social housing standards, the building offers a variety of dwellings designed to accommodate different household compositions. Family structures are heterogeneous and constantly evolving, with new uses entering the home and intimacy becoming more fluid. In the past, intimacy was primarily associated with a bedroom and its objects, but the concept has become more ambiguous, and now privacy lies in our hands, our phones, and other devices. In response to these emerging lifestyles, the architects envisioned the dwelling as a place to be inhabited in a porous and permeable manner, accommodating these changing needs.

This collective housing is organised around a courtyard. The housing units are conceived as a matrix of connected rooms of equal size, 13 m², totalling 114 rooms per floor and 543 rooms in the entire building. Dwellings are formed by the addition of 5 or 6 rooms, resulting in 18 dwellings per floor, which benefit from cross ventilation and the absence of internal corridors.

While the use of mass timber as an element of the construction was not a requisite of the competition, the architects opted to incorporate this material to enhance the building's degree of industrialisation. A wooden structure supports the building, made of 8,300 m² of timber from the Basque Country. The use of timber would improve construction quality and precision, reduce execution times, and significantly lower CO2 emissions.

De-hierarchisation of housing layouts

The project is conceived from the inside out, emphasising the development of rooms over the aggregation of dwellings. Inspired by the Japanese room of eight tatamis and its underlying philosophy, the architects aimed for adaptability through neutrality. In the Japanese house, rooms are not named by their specific use but by the tatami count, which is related to the human scale (90 x 180 cm). These polyvalent rooms are often connected on all four sides, creating great porosity and a fluidity of movement between them. The Japanese term ma has a similar meaning to room, but it transcends space by incorporating time as well. This concept highlights the neutrality of the Japanese room, which can accommodate different activities at specific times and can be transformed by such uses.

Contrary to traditional typologies of social housing in Spain, which often follow the minimum room sizes for a bedroom of 6, 8, and 10 m2 stipulated in building codes, this building adopted more generous room sizes by reducing living room space and omitting corridors. P+T anticipated that new forms of dwelling would decrease the importance of a large living room and room specialisation. For many decades, watching TV together has been a social activity within families. Increasingly, new devices and technologies are transforming screens into individual sources of entertainment. The architects determined that the minimum size of a room to facilitate ambiguity of use was 3.60 x 3.60m. Moreover, the multiple connections between spaces promote circulation patterns in which the user can wander through the dwelling endlessly. In this way, the rigid grid of the floor plan is transformed into an adaptable layout, allowing for various spatial arrangements and an ‘enfilade’ of rooms that make the space appear larger. Nevertheless, the location of the bathroom and kitchen spaces suggests, rather than imposes, the location of certain uses in their proximities. The open kitchen is located in the central room, acting as a distribution space that replaces the corridors while simultaneously making domestic work visible and challenging gender roles.

By undermining the hierarchical relation between primary and secondary rooms and eradicating the hegemony of the living room, the room distribution facilitates adaptability over time through its ambiguity of use. In this case, flexibility is achieved not by movable walls but by generous rooms that can be appropriated in multiple ways, connected or separated, achieving spatial polyvalency.

Degrees of porosity to enhance social sustainability

The architects believed that to enhance social sustainability, the building should become a support (in the sense of Open Building and Habraken’s theories) that fosters human relations and encounters between neighbours and household members. In this case there was no existing community, so to encourage the creation of such, the inner courtyard becomes the in-between space linking the public and the private realms, and the place from which the residents access to their dwellings. The gabion walls of the courtyard improve the acoustic performance of this semi-private space. P+T promote the idea of a privacy gradient between communal and the private spaces in their projects. In the case of Cornellà, the access to most dwellings from the terraces creates a connection between the communal and the private, suggesting that dwelling entrances act as filters rather than borders. Connecting this terrace to two of the rooms in a dwelling also provides the option for dual access, allowing the independent use of these rooms while favouring long-term adaptability. Inside the dwelling, the omission of corridors and the proliferation of connecting doors between spaces encourage human relationships and makes them indeterminate. This degree of connectedness between spaces and household members is defined by the degree of porosity chosen by the residents. At the same time, the porosity impacts the freedom to appropriate the space, giving greater importance to the furnishing of fixed areas within a space, such as the corners.

Reduction as an environmental strategy

The short distances defined by the non-hierarchical grid facilitated an optimal structural span for a timber structure. Although, the architects had initially proposed a wall-bearing CLT system, the design was optimised for economic viability by collaborating with timber manufacturers once construction started. This allowed the design team to assess the amount of timber and to research how it could be left visible, seeking to take advantage of all its hygrothermal benefits in the dwellings. It is evident that the greater the distance between structural supports, the more flexible the building is. But the greater this distance, the more material is needed for each structural component, and therefore the greater the environmental footprint. As a result of this collaborative optimisation process, two interior supporting rings were incorporated to the post and beam strategy, which significantly increased the adaptability of the building in the long term as well as halving the amount of timber needed. The façade and stair core continued to use wall-bearing CLT components, bracing the structure against wind and reducing the width of the pillars of the interior structure.

The building features galvanised steel connections between columns and girders, ensuring their continuity and facilitating the installation of services through open joints. Additionally, the high degree of industrialisation of the timber components, achieved through computer numerical control (CNC), optimised and ensured precise assembly. This mechanical connection between components permits the future disassembly if necessary, thereby contributing to a circular economy. To meet acoustic and fire safety requirements, a layer of sand and rockwool was placed on top of the CLT slabs of the flooring, between the timber and the screed, separating the dry and the humid works.

The environmental approach focuses on reducing building layers, drawing inspiration from vernacular architecture. However, unlike traditional building techniques which rely on manual labour, P+T employed prefabricated components to leverage the industry’s precision and reduce work, optimising the use of materials. This reductionist strategy enables them to maximise resources, cut costs, and lower emissions. As a result, the amount of timber actually used in the construction was half the amount proposed in the competition. Moreover, they minimised the number of elements and materials used. For example, an efficient use of folds and geometry eliminated the need for handrails, significantly reducing iron usage and lowering the building's overall carbon footprint.

The dwellings in Cornellà have garnered significant interest, receiving 25 awards from national and international organisations since 2021. Frequent visits from industry professionals, developers, architects, tourists and locals, demonstrate how this exemplary building, promoted by a public institution, may lead the way to more public and private developments that push the boundaries of innovation in future housing solutions.

C.Martín (ESR14)

Read more

->

Knight’s Walk (Lambeth's Homes)

Created on 26-07-2024

The review of this case study is structured to address aspects of architectural design, construction approach, and sustainability integration. The analysis draws on a range of data sources, including project design and access statements, sustainability statements, design drawings, planning applications, associated communications and archival records obtained from the planners, public records and the London Borough of Lambeth planning portal.

1. Design statement

The project site stretches to approximately 0.86 hectares, 84 residential units at a density of 215 dwellings per hectare are planned to be housed on the site. The surrounding areas are characterised by the prevalence of historic conservation areas. The site is located on the western side of the Cotton Garden Estate and is known for its public park and distinctive 22-storey Ebenezer, Hurley and Fairford towers. To the north is the Walcot Road Conservation Area with its three-storey terraced houses. To the east is Renfrew Roadside, which contains several listed buildings, including the Magistrates Court, the former Lambeth Fire Station and Workhouse (later converted to Lambeth Hospital) and what is now The Cinema Museum (Mae, 2017). Figure 1 illustrates the location of the project within the urban fabric of London.

In response to the unique characteristics and features of the site, the design team developed a comprehensive strategy to integrate the development. Firstly, the scale and massing have been carefully balanced in order to harmonize with the surrounding area. This is achieved through the use of graduated massing and a deliberate emphasis on the incorporation of open spaces and parks (Mae, 2017). Secondly, the existing transport and vehicular access has been maintained to avoid creating new routes. Thirdly, a car-free zone has been established, with the number of parking spaces on the site limited to eight, exclusively for residential units. Additionally, a number of bicycle parking bays have been installed to provide secure and convenient storage for cyclists. Fourthly, the "The Walk" concept has been implemented, offering a pedestrian route designed with human needs in mind, in an aim to promote connectivity between the site, parks, buildings, and existing public areas. This includes creating gateways and landmarks to enhance the sense of procession along the footpaths. Moreover, a balanced integration of soft and hard landscape elements was pursued to foster a sense of cohesive connectivity while preserving the site's architectural heritage (Mae, 2017). Figure 2 provides a comparative visual representation of the former site against the proposed design. Figure 2 provides a comparative visual representation of the former site against the proposed design for Knight’s Walk.

From a typological perspective, a total of 84 units have been developed, ranging in size from 54 square metres for the smallest units to 90 square metres for the largest. Phase one comprises 16 flats, including 10 one-bedroom flats, three two-bedroom flats and three three-bedroom flats. In contrast, phase two offers a broader choice with 15 one-bedroom flats, 38 two-bedroom flats and 15 three-bedroom flats.

With regard to architectural design, three key design considerations were identified as being of particular importance (HDA, 2022; Mae, 2017). The primary concern was the accessibility of the site for its residents, with particular attention paid to the needs of senior citizens and those with special requirements. This emphasis is particularly pronounced in Phase One, where the majority of units have been designed to meet both the Building Regulations Part M (which provides guidance on access to and use of buildings, including facilities for disabled occupants and easy movement through a building), and the prescribed national standards for accessible spaces (Mae, 2017). Secondly, the efficient use of space was prioritised, with the use of simple and clean architectural lines to optimise the functionality within each unit and the circulation areas. Thirdly, the well-being of residents was a significant consideration, with each unit featuring a terrace overlooking the surrounding green spaces and parks. The overall distribution of flats in both phases is shown in Figure 3.

2. Construction

In terms of construction methods, the project adopts a fabric-first approach that focuses on improving the properties of the building fabric, with the objective of optimising thermal performance, airtightness and moisture management. This approach is intended to reduce the necessity for additional mechanical or technical solutions, thereby achieving enhanced energy efficiency and comfort (Eyre et al., 2023). In addition, project planners have incorporated supplementary measures to improve construction processes (Mae, 2017). These include using a reinforced concrete structure in locations prone to thermal bridging, while avoiding cores as the primary structural support system. Furthermore, a strategy to rationalise the building’s "form factor" ensures a coherent visual progression of the building mass whilst mitigating thermal impacts such as overheating on the overall building envelope. Secondly, a balanced glazing ratio has been implemented to reduce direct thermal impacts, with the additional benefit of providing resistance to thermal mass. The use of light-coloured materials also serves to reduce the heat island effect and thermal conductivity between the exterior and interior of the building. Finally, the use of a cantilevered method, particularly in building extensions, reduces thermal bridging while improving the overall aesthetics of the structures.

3. Sustainability and energy

Several methods to promote sustainability have been integrated into the building’s envelope. The project follows the three-point model known as the "energy hierarchy", which is based on the principles of "Be Lean", "Be Clean", and "Be Green". “Be Lean” emphasizes the planning and construction of buildings that consume less energy. "Be Clean" focuses on efficiently providing and consuming energy, while "Be Green" aims to meet energy needs through renewable sources (Muralidharan, 2021).

3.1. Energy and carbon strategy

In line with energy hierarchy models, the project's energy strategy focuses on the building envelope and incorporates high-performance standards recommended by Passivhaus to optimise building mass and thermal boundaries. In addition, provisions have been made to future-proof the buildings by providing provisional spaces for future connection to planned district and central heating systems. Efforts to reduce carbon emissions centre on establishing accurate baseline emissions using the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP), implementing passive measures such as natural ventilation and high-efficiency appliances, and reducing reliance on fossil fuels for electricity generation through the use of photovoltaic cells as a secondary energy source. As a result, the buildings have achieved a 35 per cent reduction in carbon emissions compared to local regulations and similar developments (Mae, 2017; TGA, 2017).

3.2. Overheating strategy

Managing the risk of overheating has become an essential consideration in the design and construction of housing in the UK (Sameni et al., 2015). The quality of the indoor environment in any dwelling, particularly in summer, is vulnerable to excessive solar heat gain which is accentuated by the lack of rapid ventilation measures. To mitigate these challenges, the project's overheating strategy minimises internal heat generation through energy-efficient design and reduces heat gain through careful orientation, shading, windows, and insulation. Passive ventilation measures, such as natural cross-ventilation and fixed external shading, are also utilised. In addition, primary heating pipework is carefully planned to minimise losses, particularly when installed within the dwellings (TGA, 2017).

3.3. Policy and standards

The project has been developed in accordance with a complex network of interrelated policies and standards at the national, regional and local levels, in addition to mandatory national sustainability guidelines. Notably, Building Regulations Part L, which sets out specific requirements for insulation, heating systems, ventilation and fuel use, and aim to reduce carbon emissions by 31 per cent compared to those of previous regulations. Knight's Walk introduced a new layer of mandatory requirements, designated as "regional" guidelines. These guidelines are specific to the Greater London area and serve as a reference for all developments. In addition to fulfilling the national and regional regulations, the project had to comply with the requirements set forth by the local councils. Furthermore, the developer's requirements, known as Lambeth's Housing Design Standards function as a clarifying framework, outlining the pertinent policies at the national and regional levels.

As a result, the project has comfortably achieved an energy rating of B (based on the Standards Assessment Procedure calculations), with the potential to progress to an A rating. The project has developed a multi-level sustainability strategy and architectural language that considers climate, environment, and local needs, focusing on energy and carbon reduction. These strategies include encouraging active travel, increasing biodiversity and implementing adaptations to mitigate the effects of climate change through a drainage strategy and incorporating SuDS and tree planting. In addition, each flat has been fitted with mechanical ventilation with heat recovery, providing a constant supply of fresh, filtered air even when the windows are closed. All apartments are also equipped with energy-saving electrification systems to minimise electricity consumption (HDA, 2022).

4. Reflections

The section highlights both the successful aspects and the potential areas for improvement identified in the previous sections by addressing the following questions:

What methodologies were deployed within Knight’s Walk that can be classified as exemplifying ‘good’ practise?

The comprehensive assessments conducted by the designers, covering a wide range of intervention areas, facilitated the formulation of a responsible phasing strategy that mitigated the social, economic, and environmental risks associated with large-scale development projects. The early provision of alternative, well-built housing for tenants who were displaced has fostered robust collaboration between developers, designers, and local communities.

The project was developed in accordance with widely recognised accessibility standards, including compliance with Building Regulations Part M. A comprehensive assessment framework was employed to measure the quality of outcomes in line with national, regional, and local policies. In order to facilitate the adoption of improved energy efficiency strategies, consultation was undertaken with specialists versed in Passivhaus design standards. As a result of this consultation, it was determined that no additional standards were required. These strategies included the implementation of passive measures, such as massing, orientation, and material selection, complemented by high-efficiency mechanical ventilation systems, photovoltaic cells, energy-efficient appliances and well-insulated façade designs. As a result, the project achieved a Class B environmental performance during the operational phase and a diminished average national CO₂ emission for residential buildings by 80 per cent. The project's carbon production averaged 0.7 tonnes of CO₂ per year, with primary energy consumption ranging from 42 to 58 kilowatt hours per square metre (kWh/m2) (DLUHC, 2021).

What are the potential weaknesses inherent to Knight’s Walk?

Notwithstanding the robust practices that were put in place, several risks were identified, particularly in relation to the design approach that was selected. Although the fabric-first approach is regarded as a fundamental tenet of sustainable construction, it has not been without its detractors. A significant concern is the long-term variability in the performance of fabric-first buildings, which is contingent upon factors such as maintenance practices, occupant behaviour and climate fluctuations. Inadequate construction quality or maintenance practices can result in the deterioration of energy efficiency gains over time, underscoring the need for continuous monitoring and maintenance (Eyre et al., 2023). This could consequently result in a considerable increase in operational costs, thereby jeopardising the objective of housing affordability over the long term. Furthermore, buildings with high insulation using the fabric-first approach may be susceptible to overheating during the warmer seasons in certain climates, particularly if passive cooling strategies are inadequately integrated into the design (Eyre et al., 2023). This can lead to additional energy consumption for cooling purposes and counteract efforts to achieve highly efficient energy.

M.Alsaeed (ESR5)

Read more

->

The Sutton Estate Regeneration, Chelsea

Created on 03-07-2024

Innovative aspects of the housing design/building

The Deep Energy Retrofit (DER) involves four blocks with new lifts, ground floor apartments made wheelchair accessible, 81 one-to-four-bedroom flats, double glazed windows with aluminium frames and trickle vents, and re-opening closed balconies as private outdoor spaces for residents. A ground source heat pump acts as a collective heater via 200m deep piping in 25 boreholes distributing heat to each home through individual Kensa ‘shoeboxes’. The ventilation, heating, and thermal performance were designed together to allow each strategy to complement the other: insulation depth was limited, the ground source heat pump has a certain performance, and walls were made airtight.

The landscaping includes a new communal garden, natural stone hard landscaping, and soft landscaping that directs rainwater to the garden. A play trail will wind through the estate, transforming the spaces between building entrances into inviting, people-friendly areas. These will feature new trees, attractive landscaping, and enhanced facilities for bin and bike storage. The sunken garden has been updated and is a focal point for communal activity and respite. New cycle infrastructure also aims to encourage an increase in cycling as transportation. The estate office boasts a sedum roof and will be used by maintenance staff and whenever housing officers require offices on site.

Construction characteristics, materials and processes

The DER occurred while the four buildings were unoccupied. Floor plans were amended to accommodate new lifts and a greater household mix. The construction system adds the following to existing brick masonry walls: 50mm wood fibre internal insulation; 5mm reinforced lime plaster coat; double glazed windows with timber frames, aluminium fascia, and trickle vents. Where closed balconies existed, these were opened to provide some private outdoor space. Where they did not exist, prefabricated external metal balconies were fixed to the façade.

The maintenance regeneration was retrofitted with residents in situ with external façades designed to look identical to the DER. While it was preferable not to move, this was a challenge because residents have had to live with scaffolding for almost 2 years, impacting natural light and noise. During particularly disruptive periods or vulnerabilities, residents could temporarily move into vacant apartments on site. A phased approach was taken, largely block by block, where replacement of kitchens, bathrooms, boilers, and electrics occurred simultaneously on a property-by-property basis. This may mean more tenant disruption but minimises the duration of inconvenience to each home. Window replacements are being undertaken in conjunction with the external works to each block, including roof replacement, lightning conductors, pointing and brickworks repairs, and pest control measures. This maximises utilisation of the scaffold to the block, which represents a significant part of the costs, helping to achieve better value for money overall. Improvements were also made to the communal areas, door entry systems and lifts. The phasing of the 11 occupied blocks was developed to enable the scaffold to be removed in time for the landscaping works to be carried out.

Residents in all buildings were able to choose between materials and finishes: white or grey kitchen finishes, two different laminate workshops, and two vinyl floor choices. All bathrooms are finished in a white standard tile to ease maintenance.

To meet Secure by Design (SBD) requirements front doors to each block will have a metal core and timber facades. Existing windowsills are at a height of 990mm. Bars at a height of 1,100mm are, therefore, added to the window internals to adhere to modern building regulations. The fence around the sunken garden will be replaced by a metal fence at a 1,100mm height.

Energy performance characteristics

The energy performance characteristics of the DER aim to improve energy performance from a baseline of 208 kWh/m²/year to the predicted results of 111 kWh/m²/year, a 38% reduction. The following measures have been taken to improve thermal performance: airtightness; 50mm wood fibre internal insulation; 5mm reinforced lime plaster coat; double glazed windows with timber frames, aluminium fascia, and trickle vents. A new ground source heat pump with individual ‘shoeboxes’ in each apartment facilitates low and constant heat through large, low service temperature radiators. After 6 years unoccupied, the DER buildings will become occupied in late 2024. Therefore, the actual improved performance is currently unknown.

The maintenance strategy improved energy performance through the following improvements: triple glazed windows with timber frames, aluminium fascia, and trickle vents; brickwork repairs to improve airtightness; adding loft insulation; and replacing boilers with new hybrid boilers.

Involvement of users and other stakeholders

The DER turned 159 flats, mostly studios and 1-2 bedrooms, into a mix of 81 one-to-four-bedroom flats accessible by lift. This new mix was chosen to meet the demographic needs of existing residents.

Residents are integral to the Sutton Estate. Clarion’s regular printed Sutton Estate newsletter, the ‘Chelsea Chat’ was distributed to all homes across the estate in the initial stages of the project and continued until 2021. All back issues are still available online. Through the pre-application design evolution process, two Design Update leaflets, plus a questionnaire, were produced to provide residents with the opportunity to engage. Six interactive events were held throughout the pre-application process, consisting of regular online residents’ workshop, a stakeholder walkabout and a public exhibition. A design steering group was generated from within the residents to discuss designs, gain feedback, and is now used to update on construction and share concerns. For example, there was concern over many households simultaneously cooking and showering at the same time, therefore the strategy was stress tested.

Communal events are also a key component to the estate’s philosophy. These include: a resident gardening club; monthly senior lunches; trips to the seaside, pantomime, and other estates; various training events, such as media and chairing meetings; and outdoor events in the sunken garden, such a fish and chip van. Apprenticeship schemes have been implemented for gardeners, adding further social value.

Relationship to Urban Environment

The Sutton Estate, Chelsea was funded by philanthropist William Richard Sutton, who bequeathed his fortune to the creation of The Sutton Model Dwellings Trust (now Clarion Housing Group) in 1900. Due to the industrial revolution and mass migration into inner cities, the working classes in the UK were living in extreme slum conditions. According to The Chelsea Society, “in 1902 a quarter of Chelsea’s community officially lived in poverty, and 14% [sic] lived in overcrowded accommodation”, bringing sanitation issues and the “potential of a health related pandemic”, to an otherwise affluent area. Sutton left instructions to set up a trust that would build and lease social housing for “use and occupation by the poor…[in] populous places in England” (Booth, 2015; SaveOurSutton, 2018). The Sutton Estate was built between 1912-1914 on a previously dense urban site. It was the third of four social housing estates erected in Chelsea by philanthropic institutions: (1) Peabody Trust Estate, Lawrence Street, 1870; (2) Guinness Trust Estate, Kings Road, 1891; (3) Sutton Dwellings Trust Estate, Cale Street, 1912-1914; (4) Samuel Lewis Trust Estate, Ixworth Place, 1915, directly opposite the Sutton Estate (Best, 2014). By the 21st century, however, the Sutton Estate dwellings had fallen into disrepair and in desperate need of refurbishment.

The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (RBKC) is now the second most expensive borough in the UK, after Westminster, and as such The Sutton Estate sits in prime real estate location. In 2018, the RBKC rejected a planning application, in part due to a resident orchestrated campaign “Save our Sutton”, which proposed to demolish the estate and rebuild, with part of the site sold for private ownership to fund new social housing. Plans to refurbish, retrofit, and regenerate began in 2019 and were accepted in 2021.

Two of the street-facing blocks rent their ground floor to commercial shops and cafés. The residents have been historically integrated into the wider neighbourhood through shared amenities such as laundrettes, and a Tenants Association that previously organised neighbourhood fêtes. With rising costs, however, replacing affordable services with new amenities, the integration of Sutton Estate residents within the wider neighbourhood is diminishing (personal communication, 2024).

S.Furman (ESR2)

Read more

->

Flexwoningen Oosterdreef

Created on 09-02-2024

Background

The soaring housing shortage in the Netherlands has prompted national and local governments to come up with innovative solutions to cater for the ever-increasing demand. The Flexwonen model is a response to the need to provide homes quickly and to foster circularity and innovation in the construction sector. The model is crafted to meet the housing needs of people who cannot simply wait for the lengthy process of conventional housing developments or cannot afford to remain on the endless waiting list to be allocated a home.

Flexibility is its main characteristic. This is reflected not only in the design and construction features of the housing buildings, but also in the regulatory frameworks that make them possible. The faster the units are built and delivered, the greater the impact on people’s lives. This dynamic approach, which adapts to existing and evolving circumstances of homebuilding, relies on collaboration between stakeholders in the sector to streamline the procurement and building process. All of this is accompanied by an integrated approach to placemaking, exemplified by the partnership with a local social organisation, the involvement of a community builder, the provision of spaces for residents to interact and get to know each other, the project's target groups and the beneficiary selection process.

Flexwonen can have a significant impact on municipalities and regions that are severely affected by housing shortages, especially those lacking sufficient land and time to develop traditional housing projects. Due to its temporary nature, homes can be built on land that is not suitable for permanent housing. This streamlines the building process and allows the development of areas that are not currently suitable for housing, both in urban and peri-urban zones. After the initial site permit expires, the homes can be moved to another site and permanently placed there.

Recent developments in construction techniques and materials contribute to raising the aesthetic and quality standards of these projects to a level equivalent to that of permanent housing, as the case of Oosterdreef in Nieuw-Vennep demonstrates. Nevertheless, this model, propelled by the government in 2019 with the publication of the guide ‘Get started with flex-housing!’ and the ‘Temporary Housing Acceleration taskforce’ in 2022 (Druta & Fatemidokhtcharook, 2023), is still at an embryonic stage of development. The success of the initiative and its real impact, especially in the long term, remain to be seen.

Analogous housing projects have been carried out in other European countries, such as Germany, Italy, and France among others (See references section). Although their objectives and innovative aspects resonate with the ones of Flexwonen in the Netherlands, the nationwide scope of this model, sustained by the commitment and collaboration between national and local governments, social housing providers and contractors, is taking the effects of policy, building and design innovation to another level.

Involvement of stakeholders

The national government's aim to establish a more dynamic housing supply system, capable of adapting to local, regional or national demand trends in the short-term, has prompted municipalities like Haarlemmermeer to join forces with housing corporations. Together, they venture into the production of housing that can leverage site constraints while contributing to bridging the gap between supply and demand in the region.

Thanks to its innovative, flexible and collaborative nature, the Oosterdreef project was completed in less than a year after the first module was placed on the site. The land, which is owned by the municipality, is subject to environmental restrictions due to the noise pollution caused by its proximity to Schiphol airport, meaning that the construction of permanent housing was not feasible in the short term. Nevertheless, the pressing challenge of providing housing, especially for young people in the region, priced out by the private market, has led the municipality to collaborate with a housing corporation and an architecture firm. Together, they have developed a ‘Kavelpaspoort’ (plot passport), a document that significantly expedites the building process.

The plot passport is a comprehensive framework that summarises a series of requirements, restrictions, guidelines and details in a single document, developed in consultation with the various stakeholders involved. Its main purpose is to expedite the construction process. Its various benefits include helping to shorten the time it takes for the project to be approved by the relevant authorities, facilitating the selection of a suitable developer and contractors, and avoiding unforeseen issues during construction. The document is also an effective means of incorporating the voices of relevant stakeholders, including local residents before any work begins on the site. This ensures transparency and participatory decision-making. In Oosterdreef, Ymere, the housing corporation that manages the units, and FARO, the architecture firm commissioned with the design, played pivotal roles in drafting the document in collaboration with the municipality of Haarlemmermeer. Their main objective was to swiftly build houses using innovative construction techniques and to provide much-needed housing on a site that was underused due to land restrictions.

Project’s target groups and selection process

Perhaps one of the most compelling aspects of the model is the diverse group of people it intends to benefit. The target groups of Flexwonen vary according to context and needs, as the municipalities are in charge of establishing their priorities. In the case of Oosterdreef, Ymere and Haarlemmermeer aim for a social mix that not only contributes to solving the housing shortage in the region, but also supports the integration process of the status holders. The selection of status holders, i.e. asylum seekers who have received a residence permit and therefore cannot continue living in the reception centres, who would benefit from the scheme, was carried out in collaboration with the municipality and the housing corporation. As most of these residents did not previously live in the local area, as the central government determines the number of status holders that each municipality must accommodate, the social mix is attained by also including local residents. In this case, they were allocated a flat in the project based on a specific profile, as the flats were designed for single people. The project, which comprises 60 dwellings, is therefore deliberately divided to accommodate 30 of the above-mentioned status holders and 30 locals.

In addition, the group of locals was completed with emergency seekers (‘Spoed- zoekers’) and starters. The emphasis that the project's focus on this population swathe emphasises its social function. Emergency seekers are people who are unable to continue living in their homes due to severe hardship, including circumstances that severely affect their physical or mental well-being, and who are otherwise likely to be at risk of homelessness. This includes, for example, victims of domestic violence and eviction, but also people going through a life-changing situation such as divorce. On the other hand, starters, in this project between the ages of 23 and 28, refer to people who long to start on the housing ladder, e.g., recent graduates, young professionals, migrant workers and people who are unable to move from their parental home to independent living due to financial constraints.

Finally, local residents interested in the project were asked to submit a letter of motivation explaining how they would contribute to making Oosterdreef a thriving community, in addition to the usual documentation required as part of the process. Thus, a stated willingness to participate in the project was deemed more important than, for example, a place on the waiting list, demonstrating the commitment of the housing corporation and local authorities to creating a community and placemaking.

Innovative aspects of the housing design

Although this model has been applied to a range of buildings and contexts, from the temporary use of office space to the retrofitting of vacant residential buildings and the use of containers in its early stages of development (which has had a significant bearing on the stigmatisation of the model), one of the most notable features of the government's current approach to scaling up and accelerating the model is its support for the development of innovative construction techniques. The use of factory-built production methods such as prefabricated construction in the form of modules that are later transported to the site to be assembled could help to establish the model as a fully-fledged segment of the housing sector. An example of this is Homes Factory, a 3D module factory based in Breda, which was chosen as the contractor. Prefab construction not only significantly reduces the construction phases, but also makes it easier to relocate the houses when the licence expires after 15 years, which contributes to its flexibility.

The architecture firm FARO played a crucial role in shaping the plot passport, which incorporated details on the design and layout of the scheme. The objective was to encourage social interaction through shared indoor and outdoor spaces, organized around two courtyards. These courtyards are partially enclosed by two- and three-storey blocks, featuring deck access with wider-than-usual galleries with benches that offer additional space for the inhabitants to linger. Additionally, facilities such as letterboxes, entrance areas, waste collection points, and covered bicycle parking spaces were strategically placed to foster spontaneous encounters between neighbours. Some spaces, such as the courtyards, were intentionally left unfinished to encourage and enable residents to determine the function that best suits them. This provides an opportunity for residents to get to know each other, integrate, and cultivate a sense of belonging.

Within the blocks, the prefab modules consist of two different housing typologies of 32 m2 and 37 m2. One of these units on the ground floor was left unoccupied to be used as a common indoor space. The ‘Huiskamer’ or living room according to its English translation, is strategically located at the heart of the scheme, adjacent to the mailboxes and bicycle parking space. Besides serving as a place for everyone to meet and hold events, it is the place where a community builder interacts and works with the residents on-site.

Construction and energy performance characteristics

The environmental sustainability of the building was at the top of the project's priorities. Off-site construction methods offer several advantages over traditional techniques, including reduced waste due to precise manufacturing at the factory, efficient material transport, less on-site disruption, shorter construction times and the reusability and circularity of the materials and the units themselves. The choice of bamboo for the façades also contributes to the project's sustainability. Bamboo is a highly renewable and fast-growing material compared to traditional timber, with a low carbon footprint as it absorbs CO2 during growth (linked to embodied carbon). It also has energy-efficient properties, such as good thermal regulation, which leads to lower energy consumption (operational carbon). This is complemented by a heat pump system and solar panels on the roofs of the buildings.

“The only thing that is not permanent is the site”

This sentiment was shared by many, if not all, individuals involved in the project whom I had the opportunity to interview for this case study. The design qualities of the project meet the standards expected for permanent housing. One of the main challenges faced by projects of this type is the perception, increasingly erroneous, that their temporary nature implies lower quality compared to permanent housing.

In this case, the houses were designed and conceived as permanent dwellings, the temporary aspect is only linked to the site. When the 15-year licence expires, the homes will be relocated to another location where they can potentially become permanent. They can also be reassembled in a different configuration if required, a possibility granted by the modular design of the dwellings.

Integration with the community

The residents were selected with the expectation that they would contribute to building a community and support the permit-holders to better adapt and integrate into the local community and surroundings. Ymere, together with a local social organisation, helps new residents in this process of integration. During the first two years following the completion of the construction phase, concurrent with tenants moving into their new homes, an on-site community builder works with residents to help them forge the social ties that will enable the development of a cohesive and thriving community. The community builder has organised a range of social activities and initiatives in collaboration with the residents in the shared spaces. These include piano lessons, communal meals, sporting activities and ‘de Weggeefkast’, or the giveaway cupboard, a communal pantry aimed at fostering a sense of neighbourly sharing and cooperation.

L.Ricaurte (ESR15)

Read more

->

ESG finance and social housing decarbonisation

Created on 05-02-2024

Over the last decades, ESG debt issuance, through green, social or sustainability-linked loans and bonds has become increasingly common. Financial markets have hailed the adoption of ESG indicators as a tool to align capital investments with environmental and social goals, such as the decarbonisation of the social housing stock. According to the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), the green debt market has experienced a 50% growth over the last five years (CBI, 2021). However, the lack of clearly established indicators and objectives has tainted the growth of green finance with a series of high-level scandals and accusations of green-washing, unjustified claims of a company’s green credentials. For example, a fraud investigation by German prosecutors into Deutsche Bank’s asset manager, DWS, has found that ESG factors were not taken into account in a large number of investments despite this being stated in the fund’s prospectus (Reuters, 2022).

To curb greenwashing and improve transparency and accountability in green investments, the EU has embarked on an ambitious legislative agenda. This includes the first classification of environmentally sustainable economic activities: the EU Green Taxonomy (Regulation 2020/852). The Taxonomy is directly linked to the European Commission’s decarbonisation strategy, the Renovation Wave (COM (2020) 662), which relies on a combination of private and public finance to secure the investment needed for the decarbonisation of social housing.

Energy efficiency targets have become increasingly stringent as the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) and its successive recasts (COM(2021)) have been incorporated into national legislation; see for example the French Loi Climate et Resilience (2021-1104, 2021). Consequently, capital expenses for SHOs are set to increase considerably. For example, in the Netherlands, according to a Housing Europe (2020) report, attaining the 2035 energy efficiency targets set by the Dutch government will cost €116bn.

Sustainable finance legislation constitutes an expansion of the financial measures implemented by the EU in recent decades to incentivise energy efficiency standards as well as renovations in the built environment. For more detail on prior EU policies, see Economidou et al. (2020) and Bertoldi et al. (2021). The increased connections between finance and energy performance raise specific questions regarding SHOs’ access to capital markets in light of the shift toward ESG.

The rapidly expanding finance literature on green bonds draws from econometric models to explore the links between investors’ preferences and yields (Fama & French, 2007). This body of literature on asset pricing relies on the introduction of non-pecuniary preferences in investors’ utility functions together with returns and risks to explain fluctuations in the equilibrium price of capital. Drawing from a comparison between green and conventional bonds, Hachenberg and Schiereck (2018) find evidence of the former being priced at a premium. Similarly, Zerbib (2019) also shows a low but significant negative yield premium for green bonds resulting from both investors’ environmental preferences and lower risk levels. The European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (Fatica & Panzica, 2021) documents the dependency of premiums on the issuer with significant estimates for supranational institutions and corporations, but not for financial institutions. While these econometric approaches offer relevant insight into the pricing of green bonds and the incentives for issuers and investors, they do not account for the institutional particularities of social housing, a highly regulated sector usually covered by varying forms of state guarantees and subsidisation (Lawson, 2013).

ESG-labelled debt instruments & Related Legislation

Throughout the last two decades, the term ESG finance has evolved to include a large number of financial vehicles of which green bonds have become the most popular (Cortellini & Panetta, 2021). In the social housing sector, ESG comprises a broad array of tools from sustainability-linked loans to less conventional forms of finance such as carbon credits. When it comes to bonds, there is a wide variation in the sustainability credentials among the different types. Broadly speaking, green and social bonds are issued under specific ‘use of proceeds’, which means the funds raised must be used to finance projects producing clear environmental or social benefits. The issuance of these types of bonds requires a sustainable finance framework, which is usually assessed by a third party emitting an opinion on its robustness.

Sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) are an alternative to ‘use of proceeds’. Funds raised in this manner are not earmarked for sustainable projects, but can be used for general purposes. SLBs are linked to the attainment of certain company-wide Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), for example an average Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of “C” in an SHO’s housing stock. These indicators and objectives usually result in a price premium for Sustainable Bonds, or a rebate in interest rates in the case of SLBs or sustainability-linked loans (SLLs) (Cortellini & Panetta, 2021).

While there are international standards for the categorisation of green projects such as the Green Bond Principle or the Climate Bonds Strategy, strict adherence is optional and there are few legally-binding requirements resulting in a large divergence in reporting practices and external auditing. To solve these issues and prevent greenwashing, the EU has been the first regulator to embark on the formulation of a legal framework for green finance through a series of acts targeting the labelling of economic activities, investors, corporations and financial vehicles.

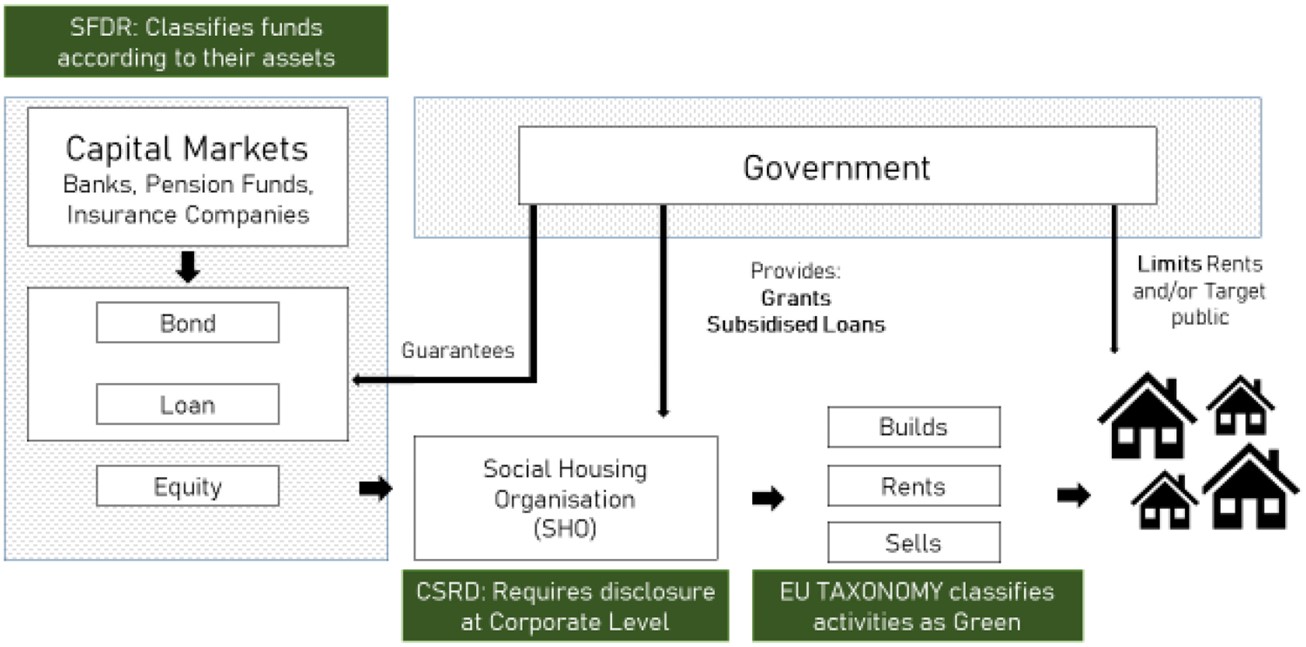

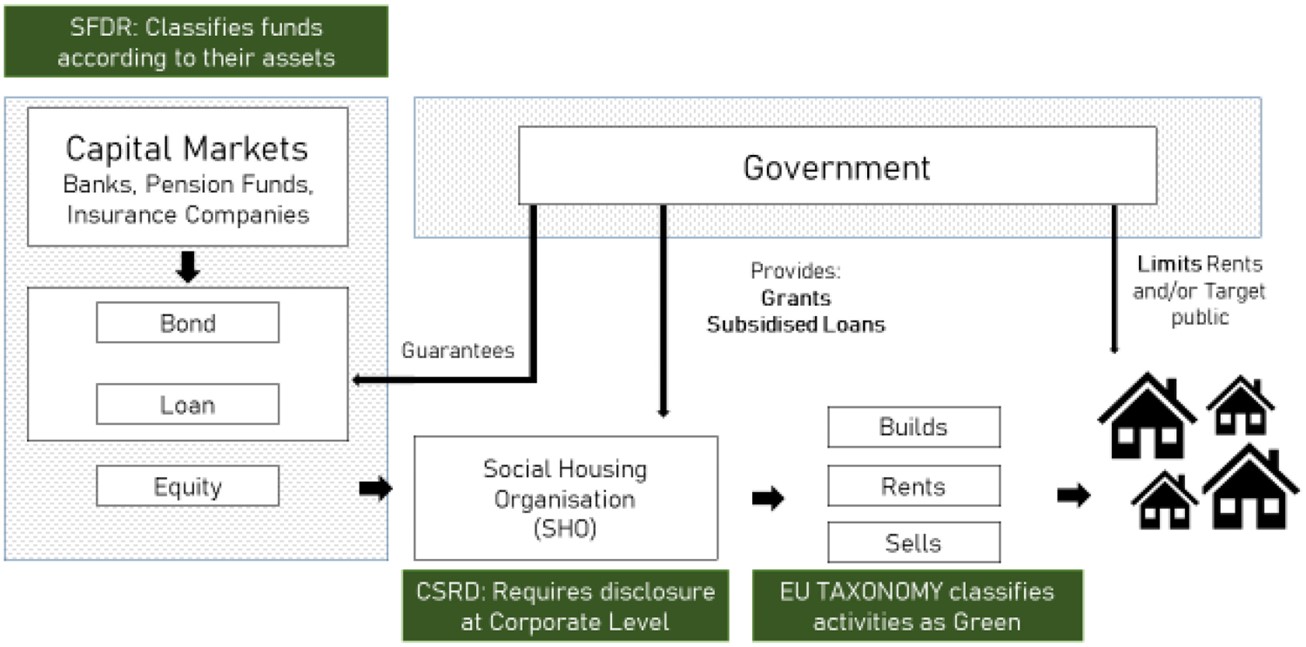

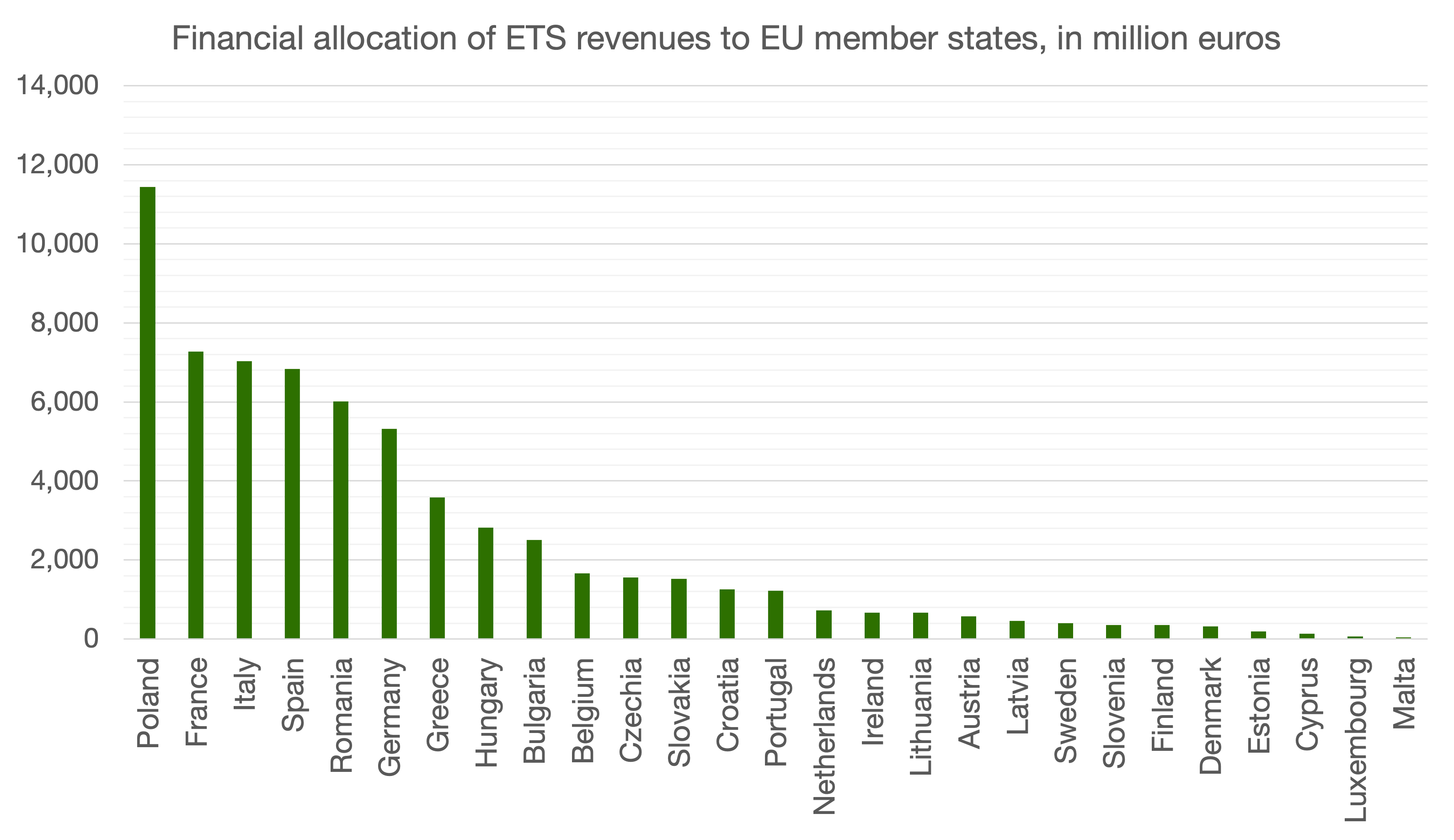

First, the EU Green Taxonomy (Regulation (EU) 2020/852) is the cornerstone of this new legislation since it classifies economic activities attending to their alignment with the objectives set in the European Green Deal (EGD). When it comes to housing, the EU Taxonomy requires specific energy efficiency levels for a project to be deemed ‘taxonomy aligned’. Second, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) (Regulation (EU) 2019/2088) mandates ESG reporting on funds, which tend to consist of exchange-traded collections of real assets, bonds or stocks. Funds are required to self-classify under article 6 with no sustainability scope, ‘light green’ article 8 which incorporates some sustainability elements, and article 9 ‘dark green’ for funds only investing in sustainability objectives. Under the SFDR, which came into effect in January 2023, fund managers are required to report the proportion of energy inefficient real estate assets as calculated by a specific formula taking into account the proportion of ‘nearly zero-energy building’, ‘primary energy demand’ and ‘energy performance certificate’ (Conrads, 2022). Third, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)(COM(2021) 189) increases disclosure requirements for corporations along Taxonomy lines. This legislation, which came into effect in 2023, will be progressively rolled out starting from larger and listed companies and expanding to a majority of companies this decade. Provisions have been made for charities and non-profits to be exempt. However, one of the key consequences of disclosure requirements over funds through the SFDR is its waterfall effect; that is the imposition of indirect reporting requirements as investors pass-on their reporting responsibilities to their borrowers. Fourth, the proposed EU Green Bonds Standards (EU-GBS) COM(2021) 391 aims to gear bond proceedings toward Taxonomy-aligned projects and increase transparency through detailed reporting and external reviewing by auditors certified by the European Security Markets Authorities (ESMA). The main objectives of these legislative changes is to create additionality, that is, steer new finance into green activities (see Figure 1).

While this new legislation is poised to increase accountability and transparency, it also aims to encourage a better management of environmental risks. According to a recent report on banking supervision by the European Central Bank (ECB), real estate is one of the major sources of risk exposure for the financial sector (ECB, 2022). This includes both physical risks, those resulting from flooding or drought and, more relevant in this case, transitional risks, that is those derived from changes in legislation such as the EPBD and transposing national legislation. The ECB points to the need for a better understanding of risk transmission channels from real estate portfolios into the financial sector through enhanced data collection and better assessments of energy efficiency, renovation costs and investing capacity. At its most extreme, non-compliance with EU regulations could result in premature devaluation and stranded assets (ECB, 2022).

In short, the introduction of reporting and oversight mechanisms connects legislation on housing’s built fabric, namely the EPBD, to financial circuits. On the one hand, the EU has been strengthening its requirements vis-à-vis energy efficiency over the last decades. The Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) suggested the introduction of Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) by Member States (Economidou et al., 2020), a rationale followed by France and the Netherlands for certain segments of the housing stock. Currently, policy-makers are debating on whether the EPBD’s recast (COM/2021/802) should incorporate MEPS and make decarbonisation an obligation for SHOs across the EU. On the other hand, legislation on green finance aims to produce incentives and oversight over investments in energy efficient renovation and new build, mobilising the private sector to cater to green projects (Renovation Wave (COM(2020) 662)).

A.Fernandez (ESR12)

Read more

->

Rural Studio

Created on 16-01-2024

“Theory and practice are not only interwoven with one’s culture but with the responsibility of shaping the environment, of breaking up social complacency, and challenging the power of the status quo.”

– Sambo Mockbee

Overview – The (Hi)Story of Rural Studio

Rural Studio is an off-campus, client-driven, design & build & place-based research studio located in the town of Newbern in Hale County in rural Alabama, and part of the curriculum of the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture of Auburn University. It was first conceptualised by Samuel “Sambo” Mockbee and D.K. Ruth as both an answer to the lack of ethical backbone in architectural education and a critique on the separation of theory and practice illustrated through the curriculum (Freear et al., 2013; Jones & Card, 2011). Both of these reasons mirrored and reinforced the way architecture was practised in the professional world in the early 1990s when, following the dominance of post-modernism, US architects were more preoccupied with matters of aesthetics and style, rather than the social and environmental aspects of their work (Oppenheimer Dean, 2002). Mockbee and Ruth aspired to create a learning environment and shape a pedagogy where students would be introduced to a real-world setting, combining theory with hands-on work and at the same time inscribing incremental, positive change on the Hale County underserved communities.

This incremental change is enabled by three main factors: (1) Auburn University’s commitment to providing stable financial support to the studio, paired with the various sponsorships that the studio receives from individual benefactors, (2) the broad network of collaborations that have been established over the years including local governing officials, external professional experts and consultants, non-profit organisations, schools, and community groups, among others, and (3) the studio’s permanent presence -and the subsequent accountability this presence fosters- in Hale County.

Unlike most design-and-build activities and programmes that adopt a “live” approach (i.e. work with/alongside real stakeholders, in real settings), Rural Studio has continuously implemented various types of projects ranging from housing and parks to community activities (e.g. farming and cooking), with five completed projects per year in Newbern and the broader Hale County area since its launching in 1993 (Freear et al., 2013; Stagg & McGlohn, 2022).

Studio structure and learning objectives

Within the Rural Studio, there are two distinct design-and-build programmes addressing third-year and fifth-year undergraduate students. As currently designed, the third-year programme primarily focuses on sharpening technical skills and exploring the process of transitioning from paper to the building site. In contrast, the fifth-year programme places greater emphasis on the social and organizational aspects of a project. Students may opt to join the Rural Studio activities either once during their third of fifth year, or twice, after spending their first two years on campus and having acquired a solid foundation in the basic skills of an architect.

Third-year programme

The third-year programme accommodates up to 16 students per semester, inviting them to reside and work in Newbern on the construction of a wooden house using platform frame construction. Until 2009, the fall semester focused on design, from conception to technical details, while the spring semester concentrated on construction, culminating in the handover of the completed project to clients or future users. However, several issues called for a profound restructuring, such as the uneven distribution of skills (with students specializing in either design or construction, rarely both), a lack of a continuous knowledge transfer from past to current projects, and students’ limited experience in collaborating with larger teams.

In its current iteration, the third-year programme is dedicated to refining technical skills – such as understanding the structural and natural properties of wood- by implementing an already designed project in phases, while complementing this process with parallel modules on building a knowledge base(Freear et al., 2013; Rural Studio, n.d.).

Seminar in aspects of design – students delve deeper in the history of the built environment of the local context, as well as the international history of wooden buildings.

“Dessein” – in this furniture-making course, students focus heavily on sharpening their wood-working skills by recreating chairs designed by well-known modernist architects.

Fifth-year programme

The fifth-year programme consists of up to 12 students, organized into teams of four, who dedicate a full academic year on a community-focused design-and-build project. These projects, collaboratively chosen by the Rural Studio teaching team and local community representatives, ensure alignment with residents’ needs and programmatic suitability for future users. The programme is student-led, requiring participants to engage in client negotiations, manage financial and material resources, and navigate the local socio-political landscape, among other tasks. Projects can be either set up to be concluded within the nine-month academic year or compartmentalized into several phases, spanning several years. In case of the latter, students are invited to stay a second year, overseeing project progress or completion, if they wish, and become mentors to the next group of fifth-year students.

Curriculum and learning Outcomes

In the Rural studio, “students learn by researching, exploring, observing, questioning, drawing, critiquing, designing, and making” In the Rural studio, “students learn by researching, exploring, observing, questioning, drawing, critiquing, designing, and making” (Freear et al., 2013, p. 34). The annual schedules, or “drumbeats,” as they are called, serve to organise and frame the activities throughout each semester. These activities are designed to enhance the skills and knowledge of students, encompassing technical and practical aspects (such as workshops on building codes, structural engineering, graphic design, and woodworking), theoretical understanding (including lectures and idea exchange sessions with invited experts), and communication skills (involving community presentations and midterm reviews). These activities are conducted in a manner that fosters a team-building approach, with creative elements like the Halloween review conducted in fancy dress, and using food as a unifying element.

In terms of learning outcomes, there are four main categories identified*:

Analysis & Synthesis (researching, exploring, observing, questioning). Students learn how to identify, analyse and navigate the parameters that can influence a design-and-build process and lay out a course of action taking everything they have identified into account.

Design & Construction (drawing, designing, making). Students learn how to navigate a project from conception to construction, and develop a deep understanding of construction technologies, environmental and structural systems, as well as the necessary technical skills to perform relevant tasks.

Teamwork & Management (exploring, questioning, critiquing, designing, making). Students learn how to work in large teams, prioritise and allocate tasks, voice their opinion, negotiate, and manage human and material resources.

Ethos & Responsibility (observing, questioning, critiquing). Through place-based immersion in the local community over the span of 4 to 9 months, students get a deeper understanding of their own role and responsibility as architects within the local sustainable development, especially in contexts of crises, and learn how to trace and assess the socio-political, financial and environmental factors that influence a project’s lifespan.

*author’s own assessment and categorisation, based on relevant readings

Context of operations: Hale County, AL