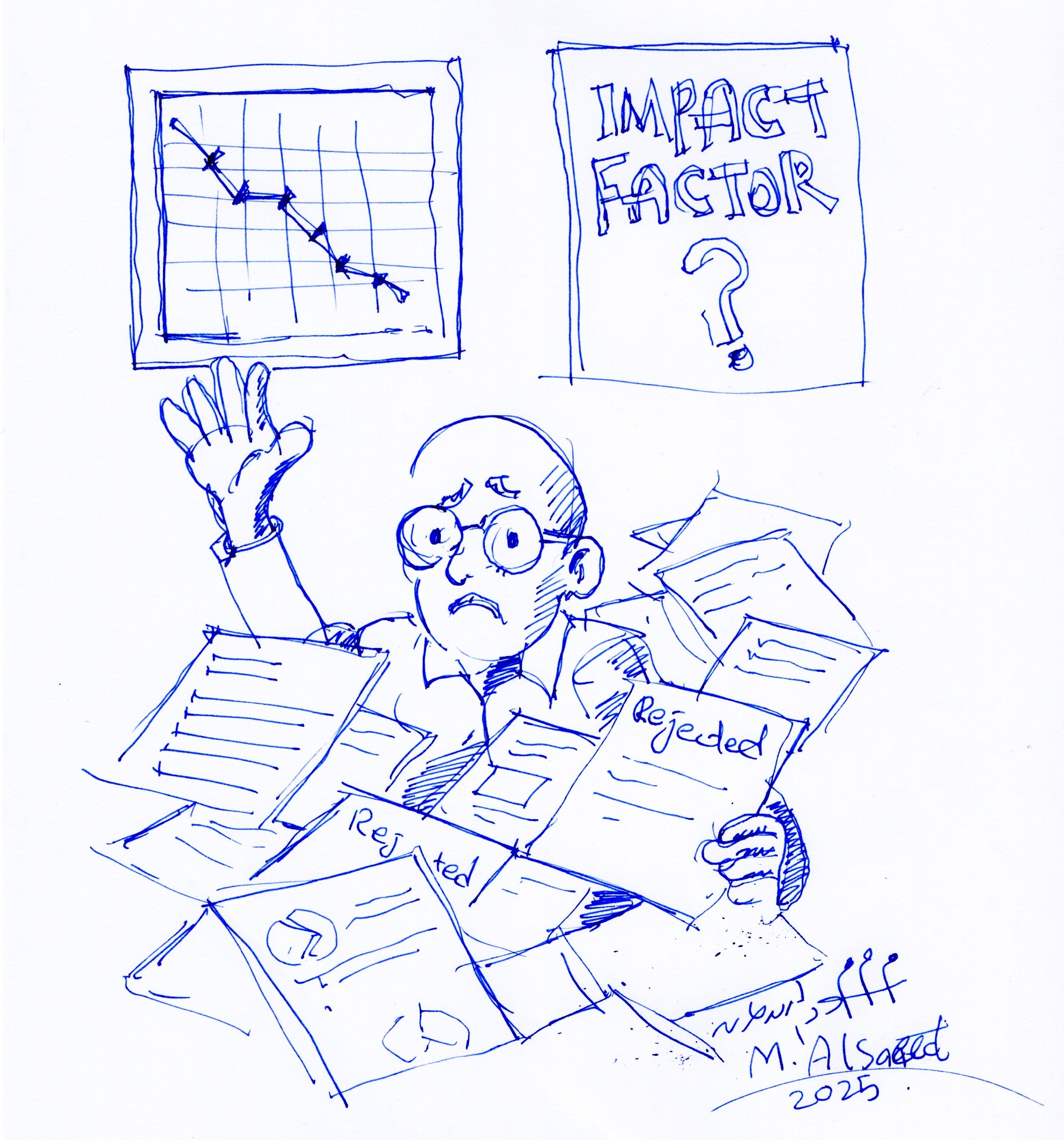

The Citation Conundrum

Posted on 19-04-2025

This post began as a five-minute conversation during a meeting last week. It was not on the agenda, spontaneous and it stuck with me. It revealed a small but telling glimpse into the more complicated, sometimes darker, side of academia and research assessment.

“I disagree, Mahmoud. I still believe citation counts are one of the most meaningful indicators we have for measuring research impact. They’re tangible and quantifiable, proof that your peers found your work relevant enough to reference.”

“I see your point, Elena” (not her real name), “but don’t you think citations only tell part of the story? Citation practices differ significantly across disciplines. For instance, citation rates in the natural sciences are far higher than those in the humanities, so comparisons become quickly misleading.”

“But Mahmoud, that’s why metrics like the h-index are useful. They balance productivity and impact, at least within the same field.”

“Okay, perhaps. But even the h-index doesn’t explain the why behind a citation. Some papers get cited not because they’re brilliant, but because they’re flawed or controversial. So in my view, citation counts often reflect visibility, not necessarily scholarly value.”

Then... silence. The conversation moved on, but I couldn’t shake it.

Over the following days, I revisited a few articles to better understand what citations actually mean. And that’s where this post comes in. It is a personal attempt to unpack the ongoing debate around the role of citation counts in academic evaluation.

So, What is a Citation Anyway?

Citations have long been used as a key indicator of academic impact. They serve as a measurable way to assess how often a piece of research is referenced in other scholarly work. At first glance, they offer clarity: the more cited a publication is, the more influential it appears to be – this is the argument I used also in my PhD about using specific article! Bornmann and Daniel (2008), in their study on citation behaviours, found that a high citation count often suggests a work has significantly contributed to its field, shaping discussions and future research. Hirsch (2005) added to this by proposing the h-index, a metric aimed at capturing both the productivity and the citation impact of a researcher’s publications.

On a personal level, I’ve found citations can act as motivation. Knowing that your work might be cited can encourage higher standards of rigour and relevance. And in many cases, highly cited papers do represent foundational or groundbreaking contributions. They help orient new scholars and identify key literature within a field.

But It’s Not That Simple

The more I reflected, the more I realised how fragile this metric can be, especially when we consider where a publication appears and in what language. English-language journals, particularly those indexed by platforms like Web of Science and Scopus, dominate the global citation landscape. As van Leeuwen et al. (2001) highlighted, this creates a systemic bias. Research written in other languages (no matter how insightful or locally impactful) is often overlooked in citation databases. This bias doesn’t just marginalise non-English research; it also sidelines entire regions, particularly in Latin America, the Middle East, Africa, and parts of Asia.

But the issue goes deeper than language, it’s geopolitical. Top-tier journals are largely situated in the Global North and embedded within Western academic networks. As a result, work that addresses region-specific challenges, employs local epistemologies, or centres non-Western knowledge systems can be left out of mainstream discourse, not because it lacks quality, but because it’s outside the dominant structures of visibility and access.

Then there’s the question of disciplinary variation. Comparing a highly cited paper on stem cell research with one exploring the subjectivity of feeling makes little sense, not because one is more important than the other, but because their fields function differently. The very nature of citation behaviour is context-dependent.

Let’s not forget questionable practices either. Fong and Wilhite (2017) exposed how self-citation, coercive citation, and citation rings can distort citation counts, undermining their credibility. And as Bornmann (2013) argues, citation metrics primarily capture academic influence, they often ignore broader contributions to society, policy, or practice.

So... What Should We Do?

Despite these limitations, citation counts aren’t without value. They can offer a snapshot, one way of looking at research influence. But they shouldn’t be treated as the sole measure of scholarly worth.

That’s where alternative metrics (or altmetrics) come into play. These consider mentions in media, social platforms, policy documents, and public discourse. They help broaden the understanding of what impact looks like in practice. Ultimately, combining quantitative tools (like citation counts and h-indexes) with qualitative assessments (like peer reviews and real-world case studies) offers a richer, fairer, and more accurate picture of academic contribution.

That five-minute conversation reminded me how much we often rely on numbers to validate our work, and how easily those numbers can mislead us. Citations matter, but so does context. So does equity. So does real-world relevance. If we’re serious about rethinking research impact, we must be willing to look beyond what’s easily counted and start valuing what’s harder to measure.

References

Bornmann, L. (2013). What is societal impact of research and how can it be assessed? A literature survey. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(2), 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22803

Bornmann, L., & Daniel, H.-D. (2008). What do citation counts measure? A review of studies on citing behaviour. Journal of Documentation, 64(1), 45–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410810844150

Hirsch, J. E. (2005). An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(46), 16569–16572. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0507655102

Van Leeuwen, T. N., Moed, H. F., Tijssen, R. J., Visser, M. S., & van Raan, A. F. (2001). Language biases in the coverage of the Science Citation Index and its consequences for international comparisons of national research performance. Scientometrics, 51(1), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010549719484

Fong, E. A., & Wilhite, A. W. (2017). Authorship and citation manipulation in academic research. PLOS ONE, 12(12), e0187394. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187394

Author:

M.Alsaeed

(ESR5)