Participatory Planning: Re-examining Community Consultation as a process that integrates the Urban Room method with a digital mapping tool

Created on 08-06-2022 | Updated on 04-07-2023

The design of new forms of democratic practices in planning and the application of new technologies to support decision making are two areas of urban planning that have been gaining momentum in recent years . Within the UK planning system, the practice of Community Consultation (CC), which is currently under review, is the main statutory method for involving citizens in local planning processes. This case study analyses the UK research project Community Consultation for Quality of Life (CCQoL) which aims to improve the process of CC by exploring ways to make civic participation in CC much more meaningful, inclusive and engaging. The combination of innovation in the physical space, using an Urban Room to conduct research and the digital tools that affect the quality of participants’ engagement are at the centre of the CCQoL project. This study provides an in-depth study of the potential of these two main methods to enhance participation and to expand and redefine the process within the framework of the Urban Living Lab.

At the time of writing, I am a participant and an observer in the University of Reading Urban Room named “Your Place Our Place”, which is taking place in March 2022. Therefore this case study analysis is part of an ongoing reflection. My role not only involves helping participants complete the mapping and participation survey, as other researchers are also doing in the field, but observing the research process from outside and conversing with the University of Reading researchers about their own observations.

Initiating entity

CCQoL project & University of Reading, UK

Objectives

Research project on the process of community consultation for planning (participatory planning research)

Educational/participatory methods

Urban Room, digital maps, survey

Context

UK planning policy, industry-driven

Place

One month in Reading - part of a wider project taking place in 4 cities in different countries within the UK

Period

Ongoing

Duration

Daily

Stakeholders

Four UK Universities, the Quality of Life Foundation (NFP organisation), Common place (a digital platform for community consultation), Urban Symbiotics (experts on inclusion) & The UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE)

Object of study

Building Event

Description

Public participation in planning is an enduring concern of scholars and practitioners regarding its practice; its inclusiveness and effectiveness. Participation can be a long-term relationship ‒ as in engagement ‒ or more short term in response to formal requirements ‒ as in consultation‒. New hands-on tools which involve innovative and experimental methods of engaging citizens are increasingly used in many countries to enhance citizen participation and collaboration in planning (AlWaer & Cooper, 2020; Rizzo et al., 2021; Scholl & Kemp, 2016). Hence, there is a growing interest in new forms of democratic practices in planning, which is fomenting the application of new technologies to support decision making.

Within the UK planning system, Community Consultation (CC) is the main statutory method for involving citizens in local planning processes. Typically, it takes place in “invited spaces” of participation that are state-led. However, some main drawbacks of the current CC processes have been pointed out (Lawson et al, 2022; Wargent & Parker, 2018); namely, under-resourced local councils, the dominance of technocratic processes that limit the scope of participation, consultation used for building consensus around new pro-growth initiatives to housing development and the uneven representation of disadvantaged groups. Recent research in the UK has revealed that CC leading to the development of a local area plan can be tokenistic, as decisions by powerful actors such as housing developers carry more weight, while input from communities comes at a time when many planning and housing design decisions have been already made (CaCHE, 2020). Official CC activities for citizen participation in the UK include the consultation on local development plans which takes place approximately every five years or the opportunity to comment on a specific planning application in a place. These processes are time consuming and demanding for community members, often involving consultation with a demographic group that is not representative. Therefore, the practice of CC is currently being reviewed in order to respond to these concerns.

Community Consultation for Quality of Life (CCQoL) is a UK-based research project that explores the ways in which civic participation in CC becomes much more meaningful, inclusive and engaging. This research project is part of four pilot projects being developed in England, Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland with the participation of community groups, academic researchers, industry partners and local authorities. One of the main methods used to investigate CC is the Urban Room concept. The Urban Room is located on the ground floor of Broad Street Mall in central Reading. Reading is a large town half an hour to the west of London by rail and is characterised by its diverse population and high density of creative industries.

The combination of innovation in the physical space, using an Urban Room for conducting research and the digital consultation tools are at the core of the CCQoL project. The key elements examined through my participation in this case study are the two foremost methods being used: (a) the establishment of an experimental Urban Room for community groups to have a platform for face-to-face participation and (b) a new method of social value mapping via a digital mapping interface available on smart phones, tablets as well as in the Urban Room and home computers. As the aim of the project is to improve planning consultation, the physical location is used for the research team to test the use of the Commonplace digital consultation platform in a real-life scenario. Commonplace is one of the leading consultation platforms in the UK. It is currently going through a period of review and will be relaunched as Commonplace 2.0 in the summer 2022.

The Urban Room

As defined by the Urban Rooms Network facilitated by the Place Alliance, the purpose of an Urban Room is:

“to foster meaningful connections between people and place, using creative methods of engagement to encourage active participation in the future of our buildings, streets and neighbourhoods”. (Urban Room Network, 2022)

Running in parallel to the activities of the Urban Room at Reading, there is a website as a platform for online participation which clearly and concisely sets out: “We need your help to develop the Quality of Life maps of Reading. These will tell us about what you value in your place and help us create a wide-ranging resource of local knowledge” (CCQoL Reading, 2022). In the physical space of the Urban Room, posters provide more information regarding the community groups and other partners involved.

The Urban Room is in a shopping centre located at the end of a very busy, pedestrianised shopping street. This space was provided free of charge by the mall’s management company, Moorgarth. There are two ways in which people usually access the room: they can either casually drop in as they pass by or attend a scheduled event. The Urban Room was organised very quickly, over four months, with a minimal budget of roughly £3,000. Most of its equipment was borrowed from the school of architecture. Great efforts have been made to promote the Urban Room through social media. As a result, the initiative has received a lot of attention from local community groups. Over the course of five weeks in March 2022, a large number of events were planned, with many community groups convened by the project’s Community Partnerships Manager. Each week had its own theme: Introduction and Business Community, Health and Wellbeing, Culture and Heritage, Climate Change and The Future of Reading. The events were planned with the dual function of providing a platform for underrepresented groups to exhibit their community actions and discuss issues that affect them and as a way of attracting people to the space.

One of the most important benefits of the Urban Room events was the opportunity for community representatives of different organisations to learn about each other’s activities and discuss about common concerns face-to-face. This makes the Urban Room a space of learning, not only about the city but about the participants. However, the establishment of an Urban Room as an experimental setting for engaging people in the creation of place-based knowledge has already presented various challenges. The fact that it is “tucked away” in a shopping centre has made it less visible to the public, making it hard to attract a diverse demographic. Also, as a quasi-public space, it has not been clear how to manage who is allowed in the room or not and at which times. Furthermore, some comments by participants indicate that there is too much information on display, especially for those on the autism spectrum, Finally, researchers have pointed out that the 60 or so workshops and activities might have been too many.

Social Value Mapping

During the activities of the Urban Room, in which as a university researcher I was a participant observer, one of the key activities that community members participated in was the use of a digital mapping tool. The main benefit of a digital consultation platform is that it can reach more people. In addition, it can be blended with physical learning.

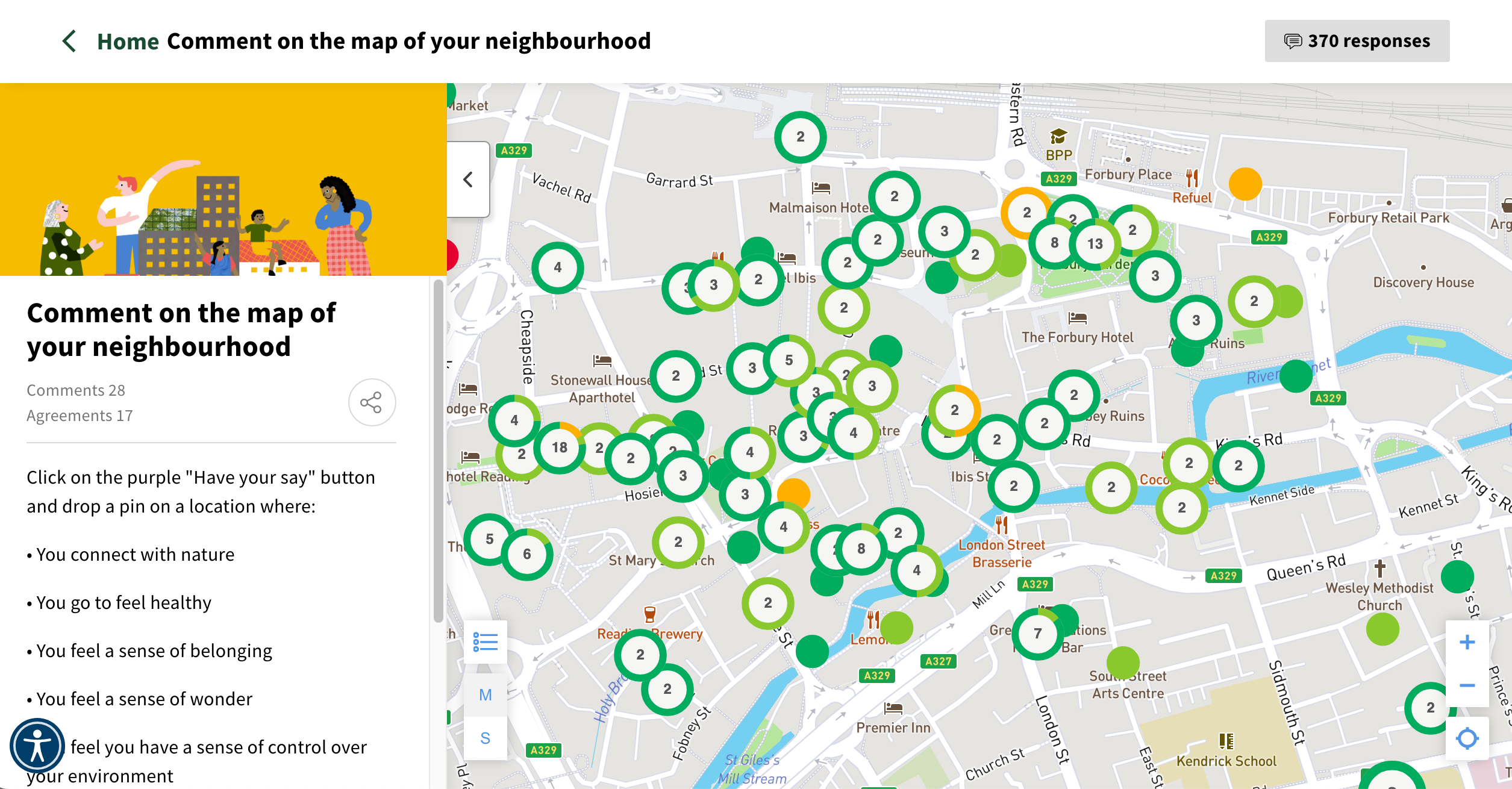

In the Commonplace platform within the Urban Room there is a map of Reading on which participants can drop a pin to locate where they (a) connect with nature; (b) feel healthy; (c) feel a sense of belonging; (d) feel a sense of wonder; (e) feel a sense of control over their environment and; (f) find it easy to get around their area. These categories are based on the Quality of Life Framework (Quality of Life Foundation, 2021) and provide the opportunity for residents of Reading to reveal qualitative data that will be then visualised in the form of a map that captures social value (Samuel & Hatleskog, 2020). Participants often show interest in the contributions that others place on the map, indicating that the tool can function as a way to establish connections and ‒ I would argue ‒ also to create social capital.

However, from the initial examination of the findings, the ability to only map the existing, positive characteristics of spaces does not allow participants to raise concerns about places they would like to see improved. The project’s research team have made an ethical decision to focus on the positive attributes of the place as the inclusion of negative impacts on publicly available maps can have a long-term negative impact on identity. Therefore, in the use of the digital mapping tool, citizens’ degree of influence and level of decision-making power remains limited. After speaking to the research team about this, I realised that consultations always need to clarify the limit of their influence. Since the research project is not an official CC linked to a real development plan, there would be a problem in addressing the participants’ concerns. Interestingly, this is a problem particularly observed in official CC processes by local governments that do not respond to the issues raised during the consultation so that community concerns are often disregarded as not being “a material consideration in a planning sense” (Lawson et al, 2022).

Therefore, contested issues and oppositional views present the difficulty of how to respond to them. However, regarding the mapping of positive characteristics, when maps are made available to the community they can provide transparency and accountability of the planning process regarding the spatial interpretation of social value.

Reflection & discussion

It can be argued that an Urban Room is similar to an Urban Living Lab (ULL) in the sense that they combine an environment and a methodology with a focus on real-life interventions by urban experimentation and collaboration between different stakeholders which has become popular in Europe (McCormick & Hartmann, 2017; Steen & van Bueren, 2017). An ULL almost always involves the goal of innovation in the face of contemporary urban challenges. Importantly, emphasis is placed on citizen-centred approaches to co-design and social innovation. However, an ULL for planning is typically used in sites for experimentation and often in a context where an intervention for alternative urban governance arrangements and sustainability transitions is taking place. Urban Rooms, on the other hand, seem to be placing more emphasis on enhancing the ties between groups of people, to provide a forum for discussion and for building awareness of local issues (Urban Room Network, 2022). Another important distinction is that an ULL places more emphasis on co-creation by involving citizens in the development of services and planning experiments (Höflehner & Zimmermann, 2016; Scholl & de Kraker, 2021; Scholl & Kemp, 2016). At the same time, co-production between local governments and citizens in collaborative planning processes is observed in design-led planning events such as charrettes (AlWaer & Cooper, 2020). Therefore, there seems to be an opportunity to redefine the Urban Room as an ULL and integrate it in planning charrettes in order to give importance to the decision-making power of participation in planning. Furthermore, despite some technical difficulties and limitations, a digital mapping tool can be a useful method of legitimising citizens’ views in planning policy, especially if it is improved to incorporate more nuanced and critical inputs.

Alignment with project research areas

The most obvious connection of the project with RE-DWELL research areas is with “Community Participation”, with community planning and vulnerable groups being the most targeted research topics. In particular, there is a focus on community planning as a process that needs to become more meaningful, inclusive and transparent.

With regard to “Design, planning and building” the CCQoL research project is involved in updating the processes leading to sustainable planning and urban regeneration by prioritising the views of under-represented groups. This becomes particularly relevant in the UK when investigating public participation in planning by the prevalent process of communication consultation.

* This diagram is for illustrative purposes only based on the author’s interpretation of the above case study

Alignment with SDGs

Particular alignment is observed with the targets:

- 11.3 “by 2030, enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management in all countries”

- 11.3.2 “proportion of cities with a direct participation structure of civil society in urban planning and management that operate regularly and democratically”

The CCQoL case study is an investigation of participation in planning which aims to determine the level of civic participation processes. Emphasis is placed on empowering marginalised groups that are regularly not given a voice in the city planning and management.

References

AlWaer, H., & Cooper, I. (2020). Changing the focus: Viewing design-led events within collaborative planning. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(8). https://doi.org/10.3390/SU12083365

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224.

CaCHE. (2020). Delivering Design Value: The housing design quality conundrum.

CCQoL Reading. (2022, March 14). Tell us about Reading and how the town affects your quality of life!, https://ccqolreading.commonplace.is

Commonplace (2022, June, 20). https://ccqolreading.commonplace.is/map/neighbourhood

Höflehner, T., & Zimmermann, F. M. (2016). An Innovation in Urban Governance : Implementing Living Labs and City Labs through Transnational Knowledge and Experience Exchange. Regional Studies Association Annual Conference, Graz, Austria, April 3-6, 2016, 1–17.

Lawson, V., Purohit, R., Samuel, F., Brennan, J., Farrelly, L.,Golden, S., & McVicair, M. (2022). Unpublished manuscript.

McCormick, K., & Hartmann, C. (2017). The emerging landscape of urban living labs: Characteristics, practices and examples. GUST- Governance of Urban Sustainability Transitions, 1–20. www.urbanlivinglabs.net

Quality of Life Foundation. (2021). The Quality of Life Framework. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.1982.tb06029.x

Rizzo, A., Habibipour, A., & Ståhlbröst, A. (2021). Transformative thinking and urban living labs in planning practice: a critical review and ongoing case studies in Europe. European Planning Studies, 0(0), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2021.1911955

Samuel, F., & Hatleskog, E. (2020). Why Social Value? In Architectural Design (Vol. 90, pp. 6–13). https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.2584

Scholl, C., & de Kraker, J. (2021). The practice of urban experimentation in Dutch city labs. Urban Planning, 6(1), 161–170. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v6i1.3626

Scholl, C., & Kemp, R. (2016). City labs as vehicles for innovation in urban planning processes. Urban Planning, 1(4), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v1i4.749

Steen, K., & van Bueren, E. (2017). The Defining Characteristics of Urban Living Labs. Technology Innovation Management Review, 7(7), 21–33. https://timreview.ca/article/1088

Urban Room Network (2022, March 16). https://urbanroomsnetwork.wordpress.com/

Wargent, M., & Parker, G. (2018). Re-imagining neighbourhood governance: the future of neighbourhood planning in England. Town Planning Review, 89(4), 379–402.

Related vocabulary

Spatial Agency

Area: Community participation

Created on 30-01-2024

Read more ->