Diagoon Houses

Created on 11-11-2022

The act of housing

The development of a space-time relationship was a revolution during the Modern Movement. How to incorporate the time variable into architecture became a fundamental matter throughout the twentieth century and became the focus of the Team 10’s research and practice. Following this concern, Herman Hertzberger tried to adapt to the change and growth of architecture by incorporating spatial polyvalency in his projects. During the post-war period, and as response to the fast and homogeneous urbanization developed using mass production technologies, John Habraken published “The three R’s for Housing” (1966) and “Supports: an Alternative to Mass Housing” (1961). He supported the idea that a dwelling should be an act as opposed to a product, and that the architect’s role should be to deliver a system through which the users could accommodate their ways of living. This means allowing personal expression in the way of inhabiting the space within the limits created by the building system. To do this, Habraken proposed differentiating between 2 spheres of control: the support which would represent all the communal decisions about housing, and the infill that would represent the individual decisions. The Diagoon Houses, built between 1967 and 1971, follow this warped and weft idea, where the warp establishes the main order of the fabric in such a way that then contrasts with the weft, giving each other meaning and purpose.

A flexible housing approach

Opposed to the standardization of mass-produced housing based on stereotypical patterns of life which cannot accommodate heterogeneous groups to models in which the form follows the function and the possibility of change is not considered, Hertzberger’s initial argument was that the design of a house should not constrain the form that a user inhabits the space, but it should allow for a set of different possibilities throughout time in an optimal way. He believed that what matters in the form is its intrinsic capability and potential as a vehicle of significance, allowing the user to create its own interpretations of the space. On the same line of thought, during their talk “Signs of Occupancy” (1979) in London, Alison and Peter Smithson highlighted the importance of creating spaces that can accommodate a variety of uses, allowing the user to discover and occupy the places that would best suit their different activities, based on patterns of light, seasons and other environmental conditions. They argued that what should stand out from a dwelling should be the style of its inhabitants, as opposed to the style of the architect. User participation has become one of the biggest achievements of social architecture, it is an approach by which many universal norms can be left aside to introduce the diversity of individuals and the aspirations of a plural society.

The Diagoon Houses, also known as the experimental carcase houses, were delivered as incomplete dwellings, an unfinished framework in which the users could define the location of the living room, bedroom, study, play, relaxing, dining etc., and adjust or enlarge the house if the composition of the family changed over time. The aim was to replace the widely spread collective labels of living patterns and allow a personal interpretation of communal life instead. This concept of delivering an unfinished product and allowing the user to complete it as a way to approach affordability has been further developed in research and practice as for example in the Incremental Housing of Alejandro Aravena.

Construction characteristics

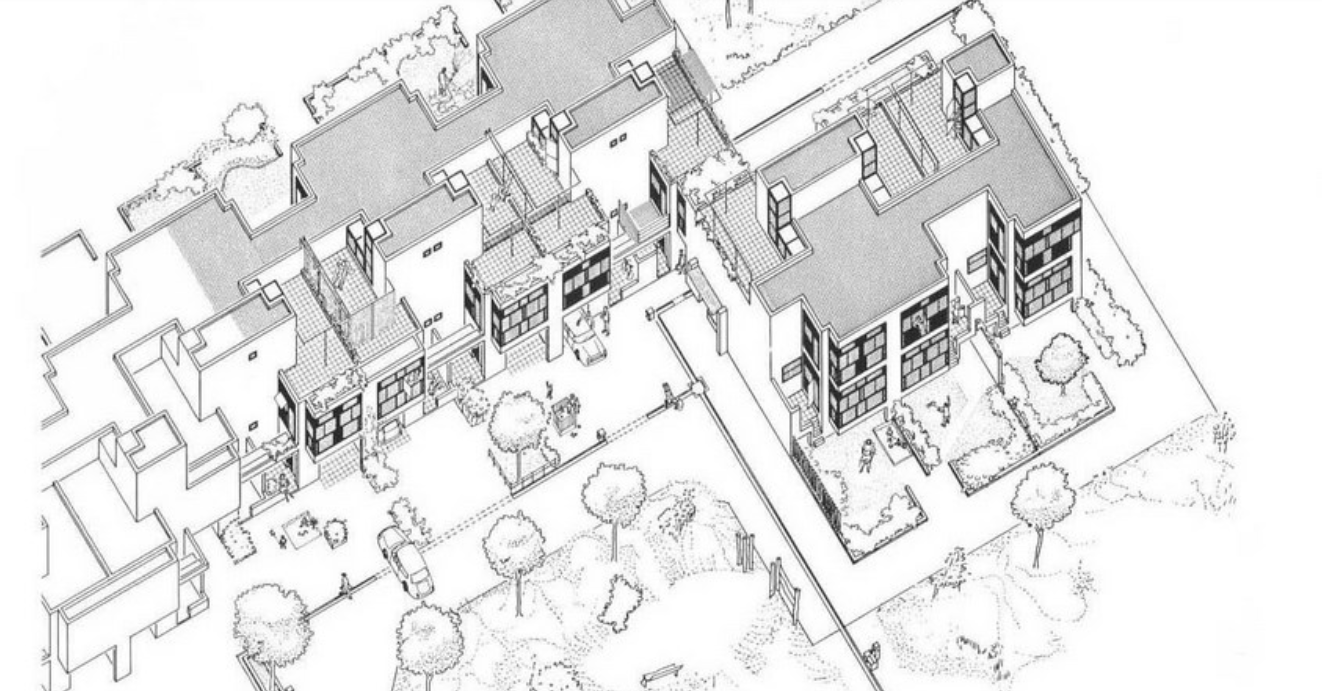

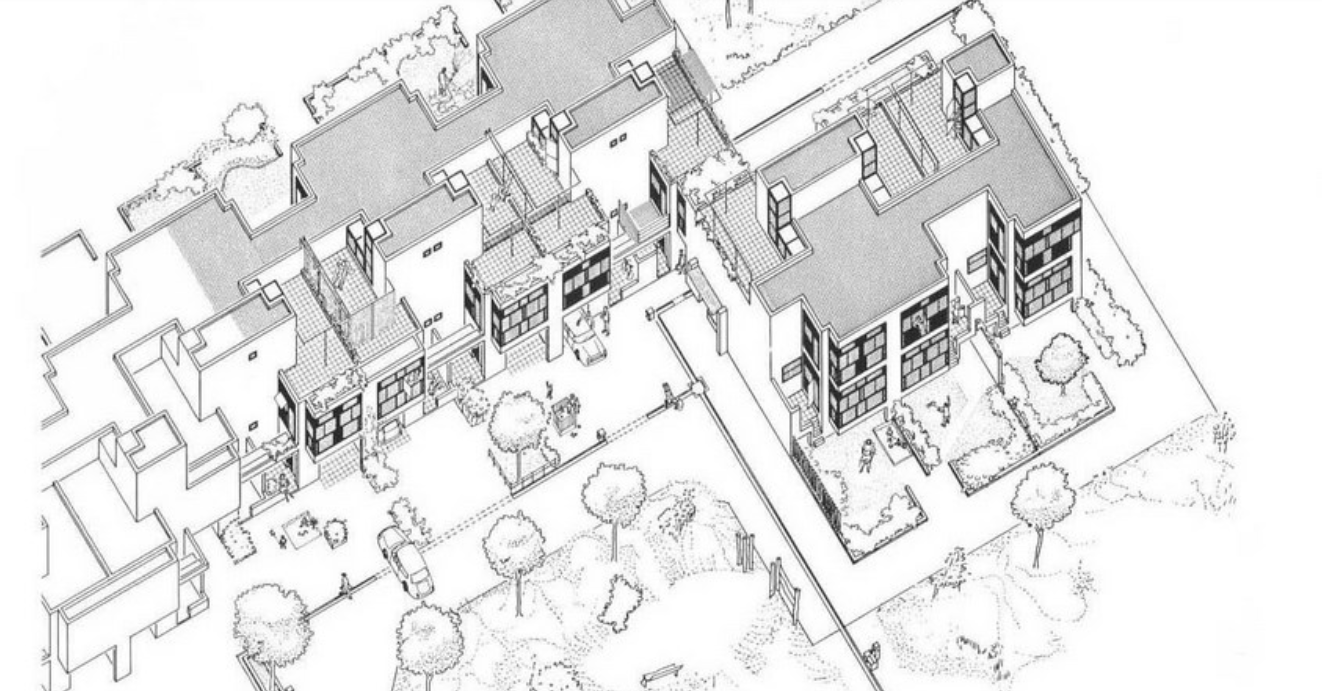

The Diagoon Houses consist of two intertwined volumes with two cores containing the staircase, toilet, kitchen and bathroom. The fact that the floors in each volume are separated only by half a storey creates a spatial articulation between the living units that allows for many optimal solutions. Hertzberger develops the support responding to the collective patterns of life, which are primary necessities to every human being. This enables the living units at each half floor to take on any function, given that the primary needs are covered by the main support. He demonstrates how the internal arrangements can be adapted to the inhabitants’ individual interpretations of the space by providing some potential distributions. Each living unit can incorporate an internal partition, leaving an interior balcony looking into the central living hall that runs the full height of the house, lighting up the space through a rooflight.

The construction system proposed by Herztberger is a combination of in-situ and mass-produced elements, maximising the use of prefabricated concrete blocks for the vertical elements to allow future modifications or additions. The Diagoon facades were designed as a framework that could easily incorporate different prefabricated infill panels that, previously selected to comply with the set regulations, would always result in a consistent façade composition. This allowance for variation at a minimal cost due to the use of prefabricated components and the design of open structures, sets the foundations of the mass customization paradigm.

User participation

While the internal interventions allow the users to covert the house to fit their individual needs, the external elements of the facade and garden could also be adapted, however in this case inhabitants must reach a mutual decision with the rest of the neighbours, reinforcing the dependency of people on one another and creating sense of community. The Diagoon Houses prove that true value of participation lies in the effects it creates in its participants. The same living spaces when seen from different eyes at different situations, resulted in unique arrangements and acquired different significance. User participation creates the emotional involvement of the inhabitant with the environment, the more the inhabitants adapt the space to their needs, the more they will be inclined to lavish care and value the things around them. In this case, the individual identity of each household lied in their unique way of interpreting a specific function, that depended on multiple factors as the place, time or circumstances. While some users felt that the house should be completed and subdivided to separate the living units, others thought that the visual connections between these spaces would reflect better their living patterns and playful arrangement between uses.

After inhabiting the house for several decades, the inhabitants of the Diagoon Houses were interviewed and all of them agreed that the house suggested the exploration of different distributions, experiencing it as “captivating, playful and challenging”1. There was general approval of the characteristic spatial and visual connection between the living units, although some users had placed internal partitions in order to achieve acoustic independence between rooms. One of the families that had been living there for more than 40 years indicated that they had made full use of the adaptability of space; the house had been subject to the changing needs of being a couple with two children, to present when the couple had already retired, and the children had left home. Another of the families that was interviewed had changed the stereotypical room naming based on functions (living room, office, dining room etc.) for floor levels (1-4), this could as well be considered a success from Hertzberger as it’s a way of liberating the space from permanent functions. Finally, there were divergent opinions with regards to the housing finishing, some thought that the house should be fitted-out, while others believed that it looked better if it was not conventionally perfect. This ability to integrate different possibilities has proven that Hertzberger’s experimental houses was a success, enhancing inclusivity and social cohesion. Despite fitting-out the inside of their homes, the exterior appearance has remained unchanged; neighbourly consideration and community identity have been realised in the design. The changes reflecting the individual identity do not disrupt the reading of the collective housing as a whole.

Spatial polivalency in contemporary housing

From a contemporary point of view, in which a housing project must be sustainable from an environmental, social and economic perspective, the strategies used for the Diagoon Houses could address some of the challenges of our time. A recent example of this would be the 85 social housing units in Cornellà by Peris+Toral Arquitectes, which exemplify how by designing polyvalent and non-hierarchical spaces and fixed wet areas, the support system has been able to accommodate different ways of appropriation by the users, embracing social sustainability and allowing future adaptations. As in Diagoon, in this new housing development the use of standardized, reusable, prefabricated elements have contributed to increasing the affordability and sustainability of the dwellings. Additionally, the use of wood as main material in the Cornellà dwellings has proved to have significant benefits for the building’s environmental impact. Nevertheless, while this matrix of equal room sizes, non-existing corridors and a centralised open kitchen has been acknowledged to avoid gender roles, some users have criticised the 13m² room size to be too restrictive for certain furniture distributions.

All in all, both the Diagoon houses and the Cornellà dwellings demonstrate that the meaning of architecture must be subject to how it contributes to improving the changing living conditions of society. Although different in terms of period, construction technologies and housing typology, these two residential buildings show strategies that allow for a reinterpretation of the domestic space, responding to the current needs of society.

C.Martín (ESR14)

Read more

->

La Borda

Created on 16-10-2024

The housing crisis

After the crisis of 2008, it became obvious that the mainstream mechanisms for the provision of housing were failing to provide secure and affordable housing for many households, especially in the countries of the European south such as Spain. It is in this context that alternative forms emerged through social initiatives. La Borda is understood as an alternative form of housing provision and a tenancy form in the historical and geographical context of Catalonia. It follows mechanisms for the provision of housing that differ from predominant approaches, which have traditionally been the free market, with a for-profit and speculative role, and a very low percentage of public provision (Allen, 2006). It also constitutes a different tenure model, based on collective instead of private ownership, which is the prevailing form in southern Europe. As such, it encompasses the notions of community engagement, self-management, co-production and democratic decision-making at the core of the project.

Alternative forms of housing

In the context of Catalonia, housing cooperatives go back to the 1960s when they were promoted by the labour movement or by religious entities. During this period, housing cooperatives were mainly focused on promoting housing development, whether as private housing developers for their members or by facilitating the development of government-protected housing. In most cases, these cooperatives were dissolved once the promotion period ended, and the homes were sold.

Some of these still exist today, such as the “Cooperativa Obrera de Viviendas” in El Prat de Llobregat. However, this model of cooperativism is significantly different from the model of “grant of use”, as it was used mostly as an organizational form, with limited or non-existent involvement of the cooperative members.

It was only after the 2008 crisis, that new initiatives have arisen, that are linked to the grant-of-use model, such as co-housing or “masoveria urbana”. The cooperative model of grant-of-use means that all residents are members of the cooperative, which owns the building. As members, they are the ones to make decisions about how it operates, including organisational, communitarian, legislative, and economic issues as well as issues concerning the building and its use. The fact that the members are not owners offers protection and provides for non-speculative development, while actions such as sub-letting or transfer of use are not possible. In the case that someone decides to leave, the flat returns to the cooperative which then decides on the new resident. This is a model that promotes long-term affordability as it prevents housing from being privatized using a condominium scheme. The grant -of -use model has a strong element of community participation, which is not always found in the other two models. International experiences were used as reference points, such as the Andel model from Denmark and the FUCVAM from Uruguay, according to the group (La Borda, 2020). However, Parés et al. (2021) believe that it is closer to the Almen model from Scandinavia, which implies collective ownership and rental, while the Andel is a co-ownership model, where the majority of its apartments have been sold to its user, thus going again back to the free-market stock.

In 2015, the city of Barcelona reached an agreement with La Borda and Princesa 49, allowing them to become the first two pilot projects to be constructed on public land with a 75-year leasehold. However, pioneering initiatives like Cal Cases (2004) and La Muralleta (1999) were launched earlier, even though they were located in peri-urban areas. The main difference is that in these cases the land was purchased by the cooperative, as there was no such legal framework at the time. This means that these projects are classified as Officially Protected Housing (Vivienda de Protección Oficial or VPO), and thus all the residents must comply with the criteria to be eligible for social housing, such as having a maximum income and not owning property. Also, since it is characterised as VPO there is a ceiling to the monthly fee to be charged for the use of the housing unit, thus keeping the housing accessible to groups with lower economic power. This makes this scheme a way to provide social housing with the active participation of the community, keeping the property public in the long term. After the agreed period, the plot will return to the municipality, or a new agreement should be signed with the cooperative.

The neighbourhood movement

In 2011, a group of neighbours occupied one of the abandoned industrial buildings in the old industrial state of Can Batlló in response to an urban renewal project, with the intention of preserving the site's memory (Can Batlló, 2020; Girbés-Peco et al., 2020). The neighbourhood movement known as "Recuperem Can Batlló" sought to explore alternative solutions to the housing crisis of the time. The project started in 2012, after a series of informal meetings with an initial group of 15 people who were already active in the neighbourhood, including members of the architectural cooperative Lacol, members of the labour cooperative La Ciutat Invisible, members of the association Sostre Civic and people from local civic associations. After a long process of public participation, where the potential uses of the site were discussed, they decided to begin a self-managed and self-promotion process to create La Borda. In 2014 they legally formed a residents’ cooperative and after a long process of negotiation with the city council, they obtained a lease for the use of the land for 75 years in exchange for an annual fee. At that time, the group expanded, and it went from 15 members to 45. After another two years of work, construction started in 2017 and the first residents moved in the following year.

The participatory process

The word “participation” is sometimes used as a buzzword, where it refers to processes of consultation or manipulation of participants to legitimise decisions, leading it to become an empty signifier. However, by identifying the hierarchies that such processes entail, we can identify higher levels of participation, that are based on horizontality, reciprocity, and mutual respect. In such processes, participants not only have equal status in decision-making, but are also able to take control and self-manage the whole process. This was the case with La Borda, a project that followed a democratic participation process, self-development, and self-management. An important element was also the transdisciplinary collaboration between the neighbours, the architects, the support entities and the professionals from the social economy sector who shared similar ideals and values.

According to Avilla-Royo et al. (2021), greater involvement and agency of dwellers throughout the lifetime of a project is a key characteristic of the cooperative housing movement in Barcelona. In that way, the group collectively discussed, imagined, and developed the housing environment that best covered their needs in typological, material, economic or managerial terms. The group of 45 people was divided into different working committees to discuss the diverse topics that were part of the housing scheme: architecture, cohabitation, economic model, legal policies, communication, and internal management. These committees formed the basis for a decision-making assembly. The committees would adapt to new needs as they arose throughout the process, for example, the “architectural” committee which was responsible for the building development, was converted into a “maintenance and self-building” committee once the building was inhabited. Apart from the specific committees, the general assembly is the place, where all the subgroups present and discuss their work. All adult members have to be part of a committee and meet every two weeks. The members’ involvement in the co-creation and management of the cooperative significantly reduced the costs and helped to create the social cohesion needed for such a project to succeed.

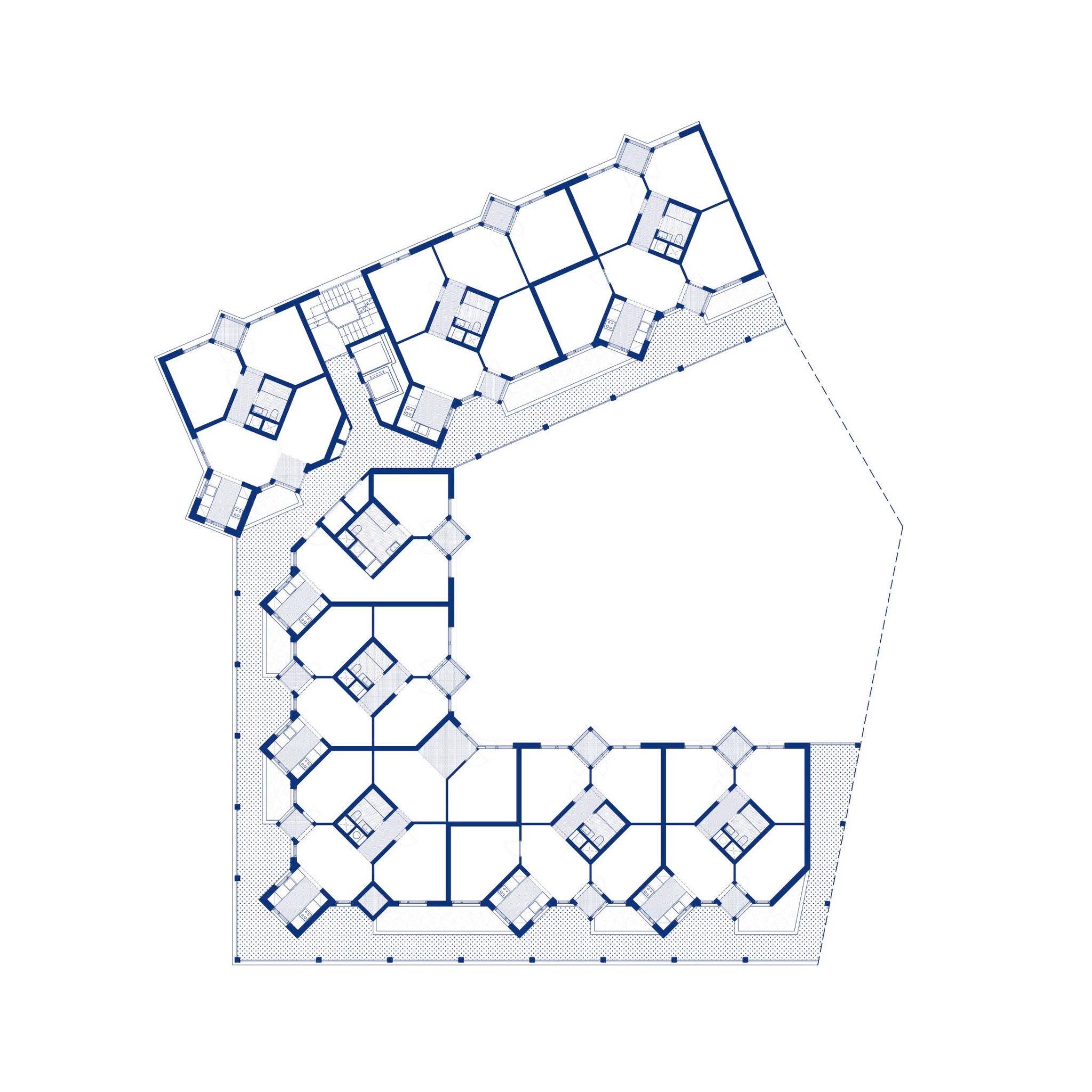

The building

After a series of workshops and discussions, the cooperative group together with architects and the rest of the team presented their conclusions on the needs of the dwellers and on the distribution of the private and communal spaces. A general strategy was to remove areas and functions from the private apartments and create bigger community spaces that could be enjoyed by everyone. As a result, 280 m2 of the total 2,950 m2 have been allocated for communal spaces, accounting for 10% of the entire built area. These spaces are placed around a central courtyard and include a community kitchen and dining room, a multipurpose room, a laundry room, a co-working space, two guest rooms, shared terraces, a small community garden, storage rooms, and bicycle parking. La Borda comprises 28 dwellings that are available in three different typologies of 40, 50 and 76 m2, catering to the needs of diverse households, including single adults, adult cohabitation, families, and single parents. The modular structure and grid system used in the construction of the dwellings offer the flexibility to modify their size in the future.

The construction of La Borda prioritized environmental sustainability and minimized embedded carbon. To achieve this, the foundation was laid as close to the surface as possible, with suspended flooring placed a meter above the ground to aid in insulation. Additionally, the building's structure utilized cross-laminated timber (CLT) from the second to the seventh floors, after the ground floor made of concrete. This choice of material had the advantage of being lightweight and low carbon. CLT was used for both the flooring and the foundation The construction prioritized the optimization of building solutions through the use of fewer materials to achieve the same purpose, while also incorporating recycled and recyclable materials and reusing waste. Furthermore, the cooperative used industrialized elements and applied waste management, separation, and monitoring. According to the members of the cooperative (LaCol, 2020b), an important element for minimizing the construction cost was the substitution of the underground parking, which was mandatory from the local legislation when you exceed a certain number of housing units, with overground parking for bicycles. La Borda was the first development that succeeded not only in being exempt from this legal requirement but also in convincing the municipality of Barcelona to change the legal framework so that new cooperative or social housing developments can obtain an “A” energy ranking without having to construct underground parking.

Energy performance goals focused on reducing energy demands through prioritizing passive strategies. This was pursued with the bioclimatic design of the building with the covered courtyard as an element that plays a central role, as it offers cross ventilation during the warm months and acts as a greenhouse during the cold months. Another passive strategy was enhanced insulation which exceeds the proposed regulation level. According to data that the cooperative published, the average energy consumption of electricity, DHW, and heating per square meter of La Borda’s dwellings is 20.25 kWh/m², which is 68% less, compared to a block of similar characteristics in the Mediterranean area, which is 62.61 kWh/m² (LaCol, 2020a). According to interviews with the residents, the building’s performance during the winter months is even better than what was predicted. Most of the apartments do not use the heating system, especially the ones that are facing south. However, the energy demands during the summer months are greater, as the passive cooling system is not very efficient due to the very high temperatures. Therefore, the group is now considering the installation of fans, air-conditioning, or an aerothermal installation that could provide a common solution for the whole building. Finally, the cooperative has recently installed solar panels to generate renewable energy.

Social impact and scalability

According to Cabré & Andrés (2018), La Borda was created in response to three contextual factors. Firstly, it was a reaction to the housing crisis which was particularly severe in Barcelona. Secondly, the emergence of cooperative movements focusing on affordable housing and social economies at that time drew attention to their importance in housing provision, both among citizens and policy-makers. Finally, the moment coincided with a strong neighbourhood movement around the urban renewal of the industrial site of Can Batlló. La Borda, as a bottom-up, self-initiated project, is not just an affordable housing cooperative but also an example of social innovation with multiple objectives beyond providing housing.

The group’s premise of a long-term leasehold was regarded as a novel way to tackle the housing crisis in Barcelona as well as a form of social innovation. The process that followed was innovative as the group had to co-create the project, which included the co-design and self-construction, the negotiation of the cession of land with the municipality, and the development of financial models for the project. Rather than being a niche project, the aim of La Borda is to promote integration with the neighbourhood. The creation of a committee to disseminate news and developments and the open days and lectures exemplify this mission. At the same time, they are actively aiming to scale up the model, offering support and knowledge to other groups. An example of this would be the two new cooperative housing projects set up by people that were on the waiting list for la Borda. Such actions lead to the creation of a strong network, where experiences and knowledge are shared, as well as resources.

The interest in alternative forms of access to housing has multiplied in recent years in Catalonia and as it is a relatively new phenomenon it is still in a process of experimentation. There are several support entities in the form of networks for the articulation of initiatives, intermediary organizations, or advisory platforms such as the cooperative Sostre Civic, the foundation La Dinamo, or initiatives such as the cooperative Ateneos, which were recently promoted by the government of Catalonia. These are also aimed at distributing knowledge and fostering a more inclusive and democratic cooperative housing movement. In the end, by fostering the community’s understanding of housing issues, and urban governance, and by seeking sustainable solutions, learning to resolve conflicts, negotiate and self-manage as well as developing mutual support networks and peer learning, these types of projects appear as both outcomes and as drivers of social transformation.

Z.Tzika (ESR10)

Read more

->

Flexwoningen Oosterdreef

Created on 09-02-2024

Background

The soaring housing shortage in the Netherlands has prompted national and local governments to come up with innovative solutions to cater for the ever-increasing demand. The Flexwonen model is a response to the need to provide homes quickly and to foster circularity and innovation in the construction sector. The model is crafted to meet the housing needs of people who cannot simply wait for the lengthy process of conventional housing developments or cannot afford to remain on the endless waiting list to be allocated a home.

Flexibility is its main characteristic. This is reflected not only in the design and construction features of the housing buildings, but also in the regulatory frameworks that make them possible. The faster the units are built and delivered, the greater the impact on people’s lives. This dynamic approach, which adapts to existing and evolving circumstances of homebuilding, relies on collaboration between stakeholders in the sector to streamline the procurement and building process. All of this is accompanied by an integrated approach to placemaking, exemplified by the partnership with a local social organisation, the involvement of a community builder, the provision of spaces for residents to interact and get to know each other, the project's target groups and the beneficiary selection process.

Flexwonen can have a significant impact on municipalities and regions that are severely affected by housing shortages, especially those lacking sufficient land and time to develop traditional housing projects. Due to its temporary nature, homes can be built on land that is not suitable for permanent housing. This streamlines the building process and allows the development of areas that are not currently suitable for housing, both in urban and peri-urban zones. After the initial site permit expires, the homes can be moved to another site and permanently placed there.

Recent developments in construction techniques and materials contribute to raising the aesthetic and quality standards of these projects to a level equivalent to that of permanent housing, as the case of Oosterdreef in Nieuw-Vennep demonstrates. Nevertheless, this model, propelled by the government in 2019 with the publication of the guide ‘Get started with flex-housing!’ and the ‘Temporary Housing Acceleration taskforce’ in 2022 (Druta & Fatemidokhtcharook, 2023), is still at an embryonic stage of development. The success of the initiative and its real impact, especially in the long term, remain to be seen.

Analogous housing projects have been carried out in other European countries, such as Germany, Italy, and France among others (See references section). Although their objectives and innovative aspects resonate with the ones of Flexwonen in the Netherlands, the nationwide scope of this model, sustained by the commitment and collaboration between national and local governments, social housing providers and contractors, is taking the effects of policy, building and design innovation to another level.

Involvement of stakeholders

The national government's aim to establish a more dynamic housing supply system, capable of adapting to local, regional or national demand trends in the short-term, has prompted municipalities like Haarlemmermeer to join forces with housing corporations. Together, they venture into the production of housing that can leverage site constraints while contributing to bridging the gap between supply and demand in the region.

Thanks to its innovative, flexible and collaborative nature, the Oosterdreef project was completed in less than a year after the first module was placed on the site. The land, which is owned by the municipality, is subject to environmental restrictions due to the noise pollution caused by its proximity to Schiphol airport, meaning that the construction of permanent housing was not feasible in the short term. Nevertheless, the pressing challenge of providing housing, especially for young people in the region, priced out by the private market, has led the municipality to collaborate with a housing corporation and an architecture firm. Together, they have developed a ‘Kavelpaspoort’ (plot passport), a document that significantly expedites the building process.

The plot passport is a comprehensive framework that summarises a series of requirements, restrictions, guidelines and details in a single document, developed in consultation with the various stakeholders involved. Its main purpose is to expedite the construction process. Its various benefits include helping to shorten the time it takes for the project to be approved by the relevant authorities, facilitating the selection of a suitable developer and contractors, and avoiding unforeseen issues during construction. The document is also an effective means of incorporating the voices of relevant stakeholders, including local residents before any work begins on the site. This ensures transparency and participatory decision-making. In Oosterdreef, Ymere, the housing corporation that manages the units, and FARO, the architecture firm commissioned with the design, played pivotal roles in drafting the document in collaboration with the municipality of Haarlemmermeer. Their main objective was to swiftly build houses using innovative construction techniques and to provide much-needed housing on a site that was underused due to land restrictions.

Project’s target groups and selection process

Perhaps one of the most compelling aspects of the model is the diverse group of people it intends to benefit. The target groups of Flexwonen vary according to context and needs, as the municipalities are in charge of establishing their priorities. In the case of Oosterdreef, Ymere and Haarlemmermeer aim for a social mix that not only contributes to solving the housing shortage in the region, but also supports the integration process of the status holders. The selection of status holders, i.e. asylum seekers who have received a residence permit and therefore cannot continue living in the reception centres, who would benefit from the scheme, was carried out in collaboration with the municipality and the housing corporation. As most of these residents did not previously live in the local area, as the central government determines the number of status holders that each municipality must accommodate, the social mix is attained by also including local residents. In this case, they were allocated a flat in the project based on a specific profile, as the flats were designed for single people. The project, which comprises 60 dwellings, is therefore deliberately divided to accommodate 30 of the above-mentioned status holders and 30 locals.

In addition, the group of locals was completed with emergency seekers (‘Spoed- zoekers’) and starters. The emphasis that the project's focus on this population swathe emphasises its social function. Emergency seekers are people who are unable to continue living in their homes due to severe hardship, including circumstances that severely affect their physical or mental well-being, and who are otherwise likely to be at risk of homelessness. This includes, for example, victims of domestic violence and eviction, but also people going through a life-changing situation such as divorce. On the other hand, starters, in this project between the ages of 23 and 28, refer to people who long to start on the housing ladder, e.g., recent graduates, young professionals, migrant workers and people who are unable to move from their parental home to independent living due to financial constraints.

Finally, local residents interested in the project were asked to submit a letter of motivation explaining how they would contribute to making Oosterdreef a thriving community, in addition to the usual documentation required as part of the process. Thus, a stated willingness to participate in the project was deemed more important than, for example, a place on the waiting list, demonstrating the commitment of the housing corporation and local authorities to creating a community and placemaking.

Innovative aspects of the housing design

Although this model has been applied to a range of buildings and contexts, from the temporary use of office space to the retrofitting of vacant residential buildings and the use of containers in its early stages of development (which has had a significant bearing on the stigmatisation of the model), one of the most notable features of the government's current approach to scaling up and accelerating the model is its support for the development of innovative construction techniques. The use of factory-built production methods such as prefabricated construction in the form of modules that are later transported to the site to be assembled could help to establish the model as a fully-fledged segment of the housing sector. An example of this is Homes Factory, a 3D module factory based in Breda, which was chosen as the contractor. Prefab construction not only significantly reduces the construction phases, but also makes it easier to relocate the houses when the licence expires after 15 years, which contributes to its flexibility.

The architecture firm FARO played a crucial role in shaping the plot passport, which incorporated details on the design and layout of the scheme. The objective was to encourage social interaction through shared indoor and outdoor spaces, organized around two courtyards. These courtyards are partially enclosed by two- and three-storey blocks, featuring deck access with wider-than-usual galleries with benches that offer additional space for the inhabitants to linger. Additionally, facilities such as letterboxes, entrance areas, waste collection points, and covered bicycle parking spaces were strategically placed to foster spontaneous encounters between neighbours. Some spaces, such as the courtyards, were intentionally left unfinished to encourage and enable residents to determine the function that best suits them. This provides an opportunity for residents to get to know each other, integrate, and cultivate a sense of belonging.

Within the blocks, the prefab modules consist of two different housing typologies of 32 m2 and 37 m2. One of these units on the ground floor was left unoccupied to be used as a common indoor space. The ‘Huiskamer’ or living room according to its English translation, is strategically located at the heart of the scheme, adjacent to the mailboxes and bicycle parking space. Besides serving as a place for everyone to meet and hold events, it is the place where a community builder interacts and works with the residents on-site.

Construction and energy performance characteristics

The environmental sustainability of the building was at the top of the project's priorities. Off-site construction methods offer several advantages over traditional techniques, including reduced waste due to precise manufacturing at the factory, efficient material transport, less on-site disruption, shorter construction times and the reusability and circularity of the materials and the units themselves. The choice of bamboo for the façades also contributes to the project's sustainability. Bamboo is a highly renewable and fast-growing material compared to traditional timber, with a low carbon footprint as it absorbs CO2 during growth (linked to embodied carbon). It also has energy-efficient properties, such as good thermal regulation, which leads to lower energy consumption (operational carbon). This is complemented by a heat pump system and solar panels on the roofs of the buildings.

“The only thing that is not permanent is the site”

This sentiment was shared by many, if not all, individuals involved in the project whom I had the opportunity to interview for this case study. The design qualities of the project meet the standards expected for permanent housing. One of the main challenges faced by projects of this type is the perception, increasingly erroneous, that their temporary nature implies lower quality compared to permanent housing.

In this case, the houses were designed and conceived as permanent dwellings, the temporary aspect is only linked to the site. When the 15-year licence expires, the homes will be relocated to another location where they can potentially become permanent. They can also be reassembled in a different configuration if required, a possibility granted by the modular design of the dwellings.

Integration with the community

The residents were selected with the expectation that they would contribute to building a community and support the permit-holders to better adapt and integrate into the local community and surroundings. Ymere, together with a local social organisation, helps new residents in this process of integration. During the first two years following the completion of the construction phase, concurrent with tenants moving into their new homes, an on-site community builder works with residents to help them forge the social ties that will enable the development of a cohesive and thriving community. The community builder has organised a range of social activities and initiatives in collaboration with the residents in the shared spaces. These include piano lessons, communal meals, sporting activities and ‘de Weggeefkast’, or the giveaway cupboard, a communal pantry aimed at fostering a sense of neighbourly sharing and cooperation.

L.Ricaurte (ESR15)

Read more

->

85 Social Housing Units in Cornellà

Created on 26-07-2024

An economic, social and environmental challenge

The architects Marta Peris and José Manuel Toral (P+T) faced the task of developing a proposal for collective housing on a site with social, economic, and environmental challenges. This social housing building won through an architectural competition organised by IMPSOL, a public body responsible for providing affordable housing in the metropolitan area of Barcelona. The block, located in the working-class neighbourhood of Sant Ildefons in Cornellà del Llobregat where the income per capita is €11,550 per year, was constructed on the site of the old Cinema Pisa. Although the cinema had closed down in 2012, the area remained a pivotal point for the community, so the social impact of the new building on the urban fabric and the existing community was of paramount importance.

The competition was won in 2017 and the housing was constructed between 2018 and 2020. The building, comprised of 85 social housing dwellings, covers a surface of 10,000m2 distributed in five floors. Adhering to a stringent budget based on social housing standards, the building offers a variety of dwellings designed to accommodate different household compositions. Family structures are heterogeneous and constantly evolving, with new uses entering the home and intimacy becoming more fluid. In the past, intimacy was primarily associated with a bedroom and its objects, but the concept has become more ambiguous, and now privacy lies in our hands, our phones, and other devices. In response to these emerging lifestyles, the architects envisioned the dwelling as a place to be inhabited in a porous and permeable manner, accommodating these changing needs.

This collective housing is organised around a courtyard. The housing units are conceived as a matrix of connected rooms of equal size, 13 m², totalling 114 rooms per floor and 543 rooms in the entire building. Dwellings are formed by the addition of 5 or 6 rooms, resulting in 18 dwellings per floor, which benefit from cross ventilation and the absence of internal corridors.

While the use of mass timber as an element of the construction was not a requisite of the competition, the architects opted to incorporate this material to enhance the building's degree of industrialisation. A wooden structure supports the building, made of 8,300 m² of timber from the Basque Country. The use of timber would improve construction quality and precision, reduce execution times, and significantly lower CO2 emissions.

De-hierarchisation of housing layouts

The project is conceived from the inside out, emphasising the development of rooms over the aggregation of dwellings. Inspired by the Japanese room of eight tatamis and its underlying philosophy, the architects aimed for adaptability through neutrality. In the Japanese house, rooms are not named by their specific use but by the tatami count, which is related to the human scale (90 x 180 cm). These polyvalent rooms are often connected on all four sides, creating great porosity and a fluidity of movement between them. The Japanese term ma has a similar meaning to room, but it transcends space by incorporating time as well. This concept highlights the neutrality of the Japanese room, which can accommodate different activities at specific times and can be transformed by such uses.

Contrary to traditional typologies of social housing in Spain, which often follow the minimum room sizes for a bedroom of 6, 8, and 10 m2 stipulated in building codes, this building adopted more generous room sizes by reducing living room space and omitting corridors. P+T anticipated that new forms of dwelling would decrease the importance of a large living room and room specialisation. For many decades, watching TV together has been a social activity within families. Increasingly, new devices and technologies are transforming screens into individual sources of entertainment. The architects determined that the minimum size of a room to facilitate ambiguity of use was 3.60 x 3.60m. Moreover, the multiple connections between spaces promote circulation patterns in which the user can wander through the dwelling endlessly. In this way, the rigid grid of the floor plan is transformed into an adaptable layout, allowing for various spatial arrangements and an ‘enfilade’ of rooms that make the space appear larger. Nevertheless, the location of the bathroom and kitchen spaces suggests, rather than imposes, the location of certain uses in their proximities. The open kitchen is located in the central room, acting as a distribution space that replaces the corridors while simultaneously making domestic work visible and challenging gender roles.

By undermining the hierarchical relation between primary and secondary rooms and eradicating the hegemony of the living room, the room distribution facilitates adaptability over time through its ambiguity of use. In this case, flexibility is achieved not by movable walls but by generous rooms that can be appropriated in multiple ways, connected or separated, achieving spatial polyvalency.

Degrees of porosity to enhance social sustainability

The architects believed that to enhance social sustainability, the building should become a support (in the sense of Open Building and Habraken’s theories) that fosters human relations and encounters between neighbours and household members. In this case there was no existing community, so to encourage the creation of such, the inner courtyard becomes the in-between space linking the public and the private realms, and the place from which the residents access to their dwellings. The gabion walls of the courtyard improve the acoustic performance of this semi-private space. P+T promote the idea of a privacy gradient between communal and the private spaces in their projects. In the case of Cornellà, the access to most dwellings from the terraces creates a connection between the communal and the private, suggesting that dwelling entrances act as filters rather than borders. Connecting this terrace to two of the rooms in a dwelling also provides the option for dual access, allowing the independent use of these rooms while favouring long-term adaptability. Inside the dwelling, the omission of corridors and the proliferation of connecting doors between spaces encourage human relationships and makes them indeterminate. This degree of connectedness between spaces and household members is defined by the degree of porosity chosen by the residents. At the same time, the porosity impacts the freedom to appropriate the space, giving greater importance to the furnishing of fixed areas within a space, such as the corners.

Reduction as an environmental strategy

The short distances defined by the non-hierarchical grid facilitated an optimal structural span for a timber structure. Although, the architects had initially proposed a wall-bearing CLT system, the design was optimised for economic viability by collaborating with timber manufacturers once construction started. This allowed the design team to assess the amount of timber and to research how it could be left visible, seeking to take advantage of all its hygrothermal benefits in the dwellings. It is evident that the greater the distance between structural supports, the more flexible the building is. But the greater this distance, the more material is needed for each structural component, and therefore the greater the environmental footprint. As a result of this collaborative optimisation process, two interior supporting rings were incorporated to the post and beam strategy, which significantly increased the adaptability of the building in the long term as well as halving the amount of timber needed. The façade and stair core continued to use wall-bearing CLT components, bracing the structure against wind and reducing the width of the pillars of the interior structure.

The building features galvanised steel connections between columns and girders, ensuring their continuity and facilitating the installation of services through open joints. Additionally, the high degree of industrialisation of the timber components, achieved through computer numerical control (CNC), optimised and ensured precise assembly. This mechanical connection between components permits the future disassembly if necessary, thereby contributing to a circular economy. To meet acoustic and fire safety requirements, a layer of sand and rockwool was placed on top of the CLT slabs of the flooring, between the timber and the screed, separating the dry and the humid works.

The environmental approach focuses on reducing building layers, drawing inspiration from vernacular architecture. However, unlike traditional building techniques which rely on manual labour, P+T employed prefabricated components to leverage the industry’s precision and reduce work, optimising the use of materials. This reductionist strategy enables them to maximise resources, cut costs, and lower emissions. As a result, the amount of timber actually used in the construction was half the amount proposed in the competition. Moreover, they minimised the number of elements and materials used. For example, an efficient use of folds and geometry eliminated the need for handrails, significantly reducing iron usage and lowering the building's overall carbon footprint.

The dwellings in Cornellà have garnered significant interest, receiving 25 awards from national and international organisations since 2021. Frequent visits from industry professionals, developers, architects, tourists and locals, demonstrate how this exemplary building, promoted by a public institution, may lead the way to more public and private developments that push the boundaries of innovation in future housing solutions.

C.Martín (ESR14)

Read more

->