Leonardo Ricaurte

ESR15

Host university

B10 - School of Built Environment, University of ReadingSupervising team

Flora Samuel (Supervisor) Lorraine Farrelly (Co-Supervisor) Jean-Cristophe Dissart (Co-Supervisor)Secondments

Clarion Housing Group, United Kingdom Institute for Sociology, Centre for Social Sciences, Hungarian Academy of Sciences Centre of Excellence, Hungary Pacte - Laboratoire de sciences sociales, Université Grenoble Alpes, FranceResearch project

ESR15 - Social Evaluation of RegenerationLeonardo holds a bachelor's degree in architecture from the National University of Colombia. He has experience in design, regulatory coordination and construction site supervision of housing projects in Bogotá. He also holds a joint Erasmus Mundus Master’s degree in International Cooperation in Urban Development and Planning between the Technical University of Darmstadt in Germany and the University of Grenoble Alpes in France. He has gained experience in participatory design activities and co-creation sessions with communities in Colombia and Germany, participating in collective projects on capacity building, urban upgrading and grassroots movements at the interface between academic and professional scenarios.

He has also gained research experience in sustainable and affordable housing projects promoting participatory practices, the Sustainable Development Goals and the New Urban Agenda through an internship at the CRAterre research laboratory in Grenoble. In 2020, he defended his Master's thesis entitled “Possibilities of participatory tools in the attainment of sustainable housing solutions: The case of Bogotá”, which was awarded a "mention très bien" by the jury. This research focused on the production of social housing in the context of international frameworks for sustainability and the impact of market-driven housing systems, urban inequality and gentrification in the development of comprehensive policies and strategies.

June, 01, 2024

September, 01, 2023

April, 01, 2022

September, 17, 2021

Design that Expands Capabilities: Assessing the Social Value of the Housing Block

This research aims to illuminate the social value of housing and its impact on people's lives, addressing an underexplored area in social value scholarship. Amid prevailing narratives that hastily attribute social issues to design flaws and equate housing estates with crime-ridden neighbourhoods and squalor, this study examines the implications of design and evaluates its effects from a human-centred perspective. By exploring the spatial dynamics of housing and the social consequences of space utilization or under-utilization, this thesis offers an alternative perspective to enrich the discourse on social value.

Contextualized within the introduction of social impact measurement policies and tools, such as the Social Value Act in England and Wales and the ESG criteria, this work focuses on the role of social housing providers and the impact they can create through procurement, design, management, and regeneration of housing stock. It proposes Amartya Sen’s capability approach as an overarching lens to guide this process, emphasizing the pivotal role of housing as a conversion factor that enables residents to live valued and flourishing lives.

Reference documents

Assessing residents' lived experiences through systematic POE can help housing associations build stronger tenant relationships and improve estate management.

ViewThis research project aims to contribute to the emerging field of measuring social value in the built environment. By focusing on housing and its design, the research project interrogates the conceptualisation of social value in the built environment, especially in the context of the Public Services (Social Value) Act in the UK. It addresses the theoretical gaps and offers a complementary approach underpinned by Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach and the pivotal role of housing as a conversion factor that enables residents to live lives they value and flourish in. To this end, the research focuses on analysing the spatial dimension of housing and the extent to which it enables a valuable state of affairs for its residents. It is therefore emphasised that a holistic assessment of social value carried out by housing providers should focus on the expansion of residents’ capabilities, in which notions of agency, control and choice, which are central factors in determining the trajectories of individual lives should be accounted for. A case study of a large housing association in the UK is used to illustrate how social value is defined, procured and measured, and the impact of current practices on residents' lives. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with residents of housing estates as well as with practitioners and housing association staff. The proposed methodology for identifying the relationship between space and wellbeing is a capability-based post-occupancy assessment, which helps to provide a fuller picture of the social value created by housing providers, architects and local authorities, particularly the more intangible and often overlooked long-term outcomes. The findings of this study are relevant to policymakers and practitioners in the field of social value and housing, along with housing providers, architects and designers who aim to better understand and evaluate the impact of design decisions on the quality of life of their tenants.

Reference documents

Capturing the social value of design in housing regeneration projects: The potential of POE and learning loops in the built environment

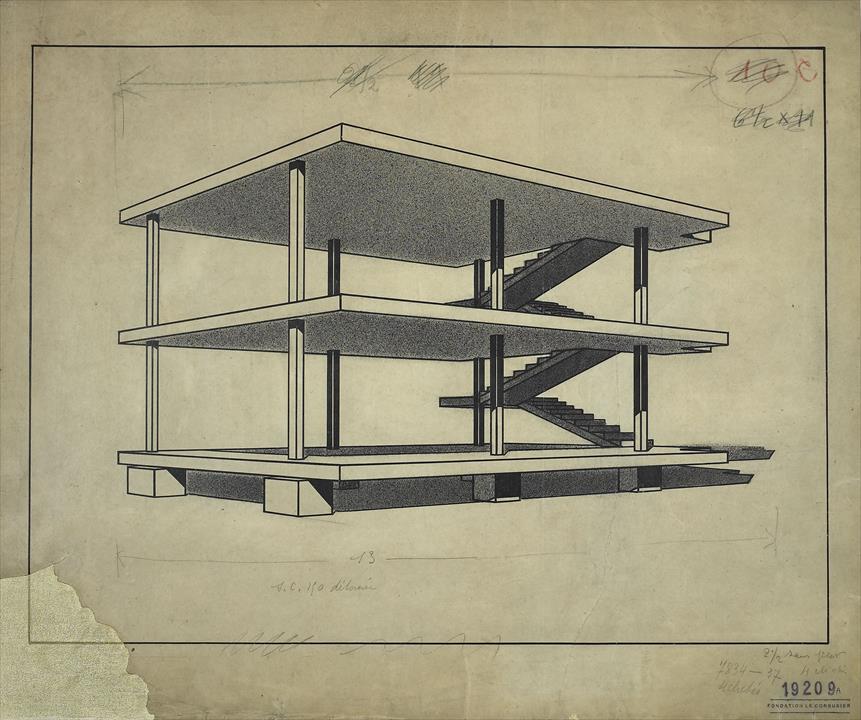

The aim of this project is to develop a framework for capturing the social value of housing at a building scale in collaboration with the housing association Clarion. Post-occupancy evaluation (POE) is a promising methodology to gauge a project’s capacity to meet social impact aims, comply with building regulations, and deliver improved sustainability and affordability (RIBA, 2020). It is subtly different to Building Performance Evaluation (BPE), whose scope tends to be limited to environmental impacts, performance benchmarks, and energy efficiency (Hay et al., 2017; Stevenson, 2019). POE has the potential to show what works in a building and what needs to be improved from the inhabitants’ point of view. When it comes to housing, a decision on the height of a bench in a common space, the position of windows in relation to a playground or the size of a stairwell can impact the social value of a project. Although architects such as Herman Hertzberger speculate about these impacts they have not been subject to systematic study or brought into line with contemporary debates about the social value of housing. This thesis seeks to align the potential of the ‘Capability approach’ of Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum with debates on social value at the scale of a housing block.

The consideration of social value as an integral aspect of POE has been advocated by several publications in recent years (Behar et al., 2017; Samuel, 2020; Watson et al., 2016; Watson & Whitley, 2017). Social Value is understood as an umbrella term that encompasses the wider economic, social and environmental effects of any given activity; it is a concept that has become very prominent, especially in the UK after the advent of the Social Value Act in 2012 (UKGBC, 2020, 2021). Since then a great deal of progress has been made in incorporating the idea of measuring quantitatively the impact of projects in communities and in general in society. Nevertheless, when it comes to the establishment of the role of the construction field in its implementation, the transition has been sluggish (Samuel & Hatleskog, 2020). The social value of design is the focus of this thesis. This research aims to complement the body of knowledge devoted to understanding how buildings work, but bringing forward the human scale and the inhabitants' interaction with and behaviour in the space. In the end, architecture should be first about people and then about buildings; or in the words of Jan Gehl: “First life, then spaces, then buildings. The other way around never works”.

Keywords: Post-Occupancy Evaluation; wellbeing assessment; housing regeneration; affordability by design; social value of design

References:

Behar, C., Bradshaw, F., Bowles, L., Croxford, B., Chen, D., Davies, J., Heaslip, M., Helliwell, T., Holgate, P., & Keeling, T. (2017). Building Knowledge: Pathways to Post Occupancy Evaluation.

Clapham, D., Foye, C., & Blyth, R. (2019). How should we evaluate housing outcomes?

Hay, R., Samuel, F., Watson, K. J., & Bradbury, S. (2017). Post-occupancy evaluation in architecture: experiences and perspectives from UK practice. Building Research & Information, 46(6), 698–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2017.1314692

RIBA. (2020). Post Occupancy Evaluation An essential tool to improve the built environment.

Samuel, F. (2020). RIBA social value toolkit for architecture. Royal Institute of British Architects.

Samuel, F., & Hatleskog, E. (2020). Why Social Value? Architectural Design, 90(4), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/AD.2584

Stevenson, F. (2019). Housing fit for purpose: Performance, feedback and learning. Routledge.

UKGBC. (2020). A guide to measuring the social value of buildings and places. https://www.ukgbc.org/ukgbc-work/delivering-social-value-measurement/

UKGBC. (2021). Framework for Defining Social Value. https://www.ukgbc.org/ukgbc-work/framework-for-defining-social-value/

Watson, K. J., Evans, J., Karvonen, A., & Whitley, T. (2016). Re-conceiving building design quality: A review of building users in their social context. Indoor + Built Environment : The Journal of the International Society of the Built Environment, 25(3), 509–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/1420326X14557550

Watson, K. J., & Whitley, T. (2017). Applying Social Return on Investment (SROI) to the built environment., 45(8), 875–891. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2016.1223486

Reference documents

Housing regeneration in Europe: Possibilities for social value creation in the context of the Renovation Wave

In the framework of integrated plans such as the Renovation Wave and the European Green Deal, several urban renewal projects are to be implemented in cities across the continent in the coming years. This depicts a remarkable opportunity to channel expertise, decision-making and funds towards better practices and trigger a paradigm shift in city-making. Accordingly, the research question that will steer the development of this study is: How can the social value and wellbeing generated by housing projects be better captured and capitalized in the context of major urban regeneration schemes?

Housing projects that envision creating more cohesive and inclusive communities will be targeted in a series of data collection activities, planned to offer the possibility of experimenting with different methods, and considering all the actors involved. The methodology to be used is a mix of quantitative and qualitative data collection processes, incorporating methods like participatory action research, and selected from the array of existing Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) frameworks and social value toolkits for architecture, selected through a systematic literature review. The feedback acquired will be instrumental in informing the development of an own tailor-made social evaluating framework. The intention is to demonstrate the benefits of conducting POE and showcasing projects that reconcile affordability and sustainability. And ultimately inspire decision-makers, private developers, academia, and civil society to get on board.

The secondments that complement this research are fundamental for the creation of tangible and productive links between academia and industry. In this aspect, the findings obtained will potentially contribute to the institutions’ own activities. Counting on Clarion’s expertise in regeneration projects for carrying out data collection activities. Consequently, England and France are subjects of a comprehensive analysis, yet other countries participants of the RE-DWELL network remain considered possible sources of input that resonates with the research aims. This study emphasizes the great potential that resides in incorporating practices such as POE, wellbeing and quality of life and social value assessment when developing housing regeneration schemes. Hence, by leveraging on the experiences and momentum, the generation of new projects could be attained.

Keywords: Post-Occupancy Evaluation; social value; Renovation Wave; quality of life; housing regeneration; affordability by design; collaborative housing

Reference documents

Architecture enables, not dictates ways of life. Good design doesn’t have to come with a hefty price tag

Posted on 02-11-2023

Secondments, Reflections

Read more ->

The “regeneration wave”, hopefully not another missed opportunity to create social value

Posted on 15-07-2023

Summer schools, Reflections

Read more ->

Creating impact through transdisciplinary housing research

Posted on 17-05-2023

Secondments, Reflections

Read more ->

'we shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us'

Posted on 07-02-2023

Secondments

Read more ->

Decoding 'new' housing paradigms

Posted on 13-01-2022

Reflections

Read more ->

Chega de Saudade, see you next time!

Posted on 29-09-2021

Workshops

Read more ->

New beginnings: paving the way towards sustainable and affordable housing for all

Posted on 19-07-2021

Workshops

Read more ->

Marmalade Lane

Created on 08-06-2022

Flexwoningen Oosterdreef

Created on 09-02-2024

Broadwater Farm Urban Design Framework

Created on 26-07-2024

Affordability

Deliberative Democracy

Participatory Approaches

Post-occupancy Evaluation

Social Value

Third place

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 03-06-2022

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 19-06-2024

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 17-02-2022

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 22-10-2023

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 16-11-2023

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 20-06-2024

Read more ->