La Borda

Created on 04-06-2022 | Updated on 16-10-2024

La Borda is a housing cooperative, located in the neighbourhood of La Bordeta-Sants in Barcelona, a working-class neighbourhood with a long tradition of cooperatives. The plot is part of the former industrial estate of Can Batlló and was the outcome of a neighbourhood movement to reclaim the area and empower its social fabric. It is an experiment that emerged from local grassroots initiatives, to provide decent, non-speculative and long-term affordable housing with the active participation of the community, as well as to minimise environmental impact and energy consumption. Through a participatory process, the group worked together with local organisations, architects, and professionals to rethink the way they wanted to dwell, questioning the individualisation of living, and suggesting more communitarian forms. They produced new forms of coexistence, social bonds, and self-organization by promoting reciprocal relations and equality. The group aspired to create a scalable alternative in the social housing field by articulating a model of accessible housing for people with lower incomes. The property is characterised as social housing, as the group managed to achieve an agreement with the municipality, which owns the plot, for a 75-year leasehold. The legal framework under which the cooperative secures long-term affordability is called “grant of use”, prioritizing the use value instead of the exchange value, thus avoiding speculation.

Architect(s)

Lacol cooperativa

Location

Barcelona, Spain

Project (year)

2012-present

Construction (year)

2017-2018

Housing type

cooperative houisng

Urban context

part of an old industrial site

Construction system

first floor with concrete and the next six with CLT

Status

Built

Description

The housing crisis

After the crisis of 2008, it became obvious that the mainstream mechanisms for the provision of housing were failing to provide secure and affordable housing for many households, especially in the countries of the European south such as Spain. It is in this context that alternative forms emerged through social initiatives. La Borda is understood as an alternative form of housing provision and a tenancy form in the historical and geographical context of Catalonia. It follows mechanisms for the provision of housing that differ from predominant approaches, which have traditionally been the free market, with a for-profit and speculative role, and a very low percentage of public provision (Allen, 2006). It also constitutes a different tenure model, based on collective instead of private ownership, which is the prevailing form in southern Europe. As such, it encompasses the notions of community engagement, self-management, co-production and democratic decision-making at the core of the project.

Alternative forms of housing

In the context of Catalonia, housing cooperatives go back to the 1960s when they were promoted by the labour movement or by religious entities. During this period, housing cooperatives were mainly focused on promoting housing development, whether as private housing developers for their members or by facilitating the development of government-protected housing. In most cases, these cooperatives were dissolved once the promotion period ended, and the homes were sold.

Some of these still exist today, such as the “Cooperativa Obrera de Viviendas” in El Prat de Llobregat. However, this model of cooperativism is significantly different from the model of “grant of use”, as it was used mostly as an organizational form, with limited or non-existent involvement of the cooperative members.

It was only after the 2008 crisis, that new initiatives have arisen, that are linked to the grant-of-use model, such as co-housing or “masoveria urbana”. The cooperative model of grant-of-use means that all residents are members of the cooperative, which owns the building. As members, they are the ones to make decisions about how it operates, including organisational, communitarian, legislative, and economic issues as well as issues concerning the building and its use. The fact that the members are not owners offers protection and provides for non-speculative development, while actions such as sub-letting or transfer of use are not possible. In the case that someone decides to leave, the flat returns to the cooperative which then decides on the new resident. This is a model that promotes long-term affordability as it prevents housing from being privatized using a condominium scheme. The grant -of -use model has a strong element of community participation, which is not always found in the other two models. International experiences were used as reference points, such as the Andel model from Denmark and the FUCVAM from Uruguay, according to the group (La Borda, 2020). However, Parés et al. (2021) believe that it is closer to the Almen model from Scandinavia, which implies collective ownership and rental, while the Andel is a co-ownership model, where the majority of its apartments have been sold to its user, thus going again back to the free-market stock.

In 2015, the city of Barcelona reached an agreement with La Borda and Princesa 49, allowing them to become the first two pilot projects to be constructed on public land with a 75-year leasehold. However, pioneering initiatives like Cal Cases (2004) and La Muralleta (1999) were launched earlier, even though they were located in peri-urban areas. The main difference is that in these cases the land was purchased by the cooperative, as there was no such legal framework at the time. This means that these projects are classified as Officially Protected Housing (Vivienda de Protección Oficial or VPO), and thus all the residents must comply with the criteria to be eligible for social housing, such as having a maximum income and not owning property. Also, since it is characterised as VPO there is a ceiling to the monthly fee to be charged for the use of the housing unit, thus keeping the housing accessible to groups with lower economic power. This makes this scheme a way to provide social housing with the active participation of the community, keeping the property public in the long term. After the agreed period, the plot will return to the municipality, or a new agreement should be signed with the cooperative.

The neighbourhood movement

In 2011, a group of neighbours occupied one of the abandoned industrial buildings in the old industrial state of Can Batlló in response to an urban renewal project, with the intention of preserving the site's memory (Can Batlló, 2020; Girbés-Peco et al., 2020). The neighbourhood movement known as "Recuperem Can Batlló" sought to explore alternative solutions to the housing crisis of the time. The project started in 2012, after a series of informal meetings with an initial group of 15 people who were already active in the neighbourhood, including members of the architectural cooperative Lacol, members of the labour cooperative La Ciutat Invisible, members of the association Sostre Civic and people from local civic associations. After a long process of public participation, where the potential uses of the site were discussed, they decided to begin a self-managed and self-promotion process to create La Borda. In 2014 they legally formed a residents’ cooperative and after a long process of negotiation with the city council, they obtained a lease for the use of the land for 75 years in exchange for an annual fee. At that time, the group expanded, and it went from 15 members to 45. After another two years of work, construction started in 2017 and the first residents moved in the following year.

The participatory process

The word “participation” is sometimes used as a buzzword, where it refers to processes of consultation or manipulation of participants to legitimise decisions, leading it to become an empty signifier. However, by identifying the hierarchies that such processes entail, we can identify higher levels of participation, that are based on horizontality, reciprocity, and mutual respect. In such processes, participants not only have equal status in decision-making, but are also able to take control and self-manage the whole process. This was the case with La Borda, a project that followed a democratic participation process, self-development, and self-management. An important element was also the transdisciplinary collaboration between the neighbours, the architects, the support entities and the professionals from the social economy sector who shared similar ideals and values.

According to Avilla-Royo et al. (2021), greater involvement and agency of dwellers throughout the lifetime of a project is a key characteristic of the cooperative housing movement in Barcelona. In that way, the group collectively discussed, imagined, and developed the housing environment that best covered their needs in typological, material, economic or managerial terms. The group of 45 people was divided into different working committees to discuss the diverse topics that were part of the housing scheme: architecture, cohabitation, economic model, legal policies, communication, and internal management. These committees formed the basis for a decision-making assembly. The committees would adapt to new needs as they arose throughout the process, for example, the “architectural” committee which was responsible for the building development, was converted into a “maintenance and self-building” committee once the building was inhabited. Apart from the specific committees, the general assembly is the place, where all the subgroups present and discuss their work. All adult members have to be part of a committee and meet every two weeks. The members’ involvement in the co-creation and management of the cooperative significantly reduced the costs and helped to create the social cohesion needed for such a project to succeed.

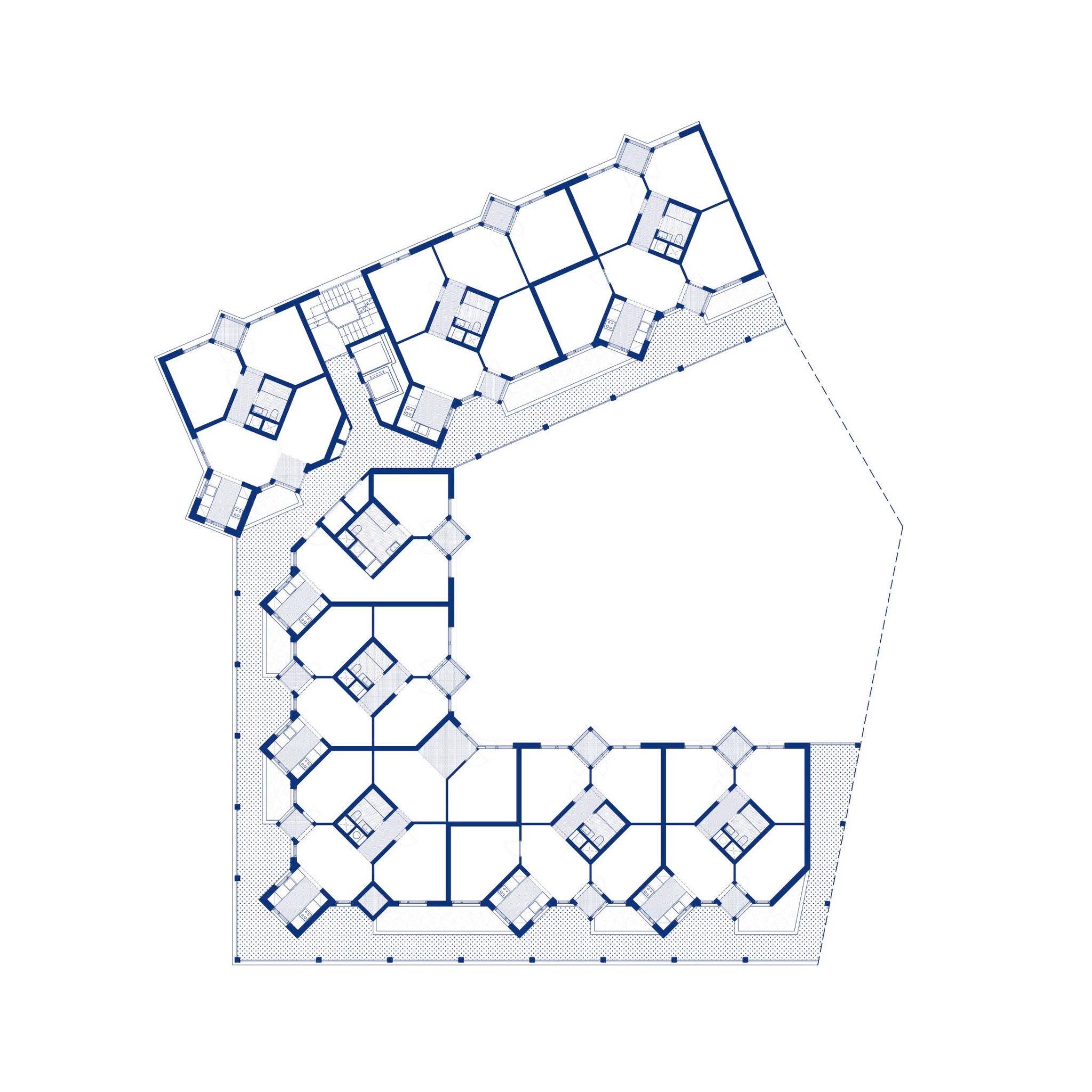

The building

After a series of workshops and discussions, the cooperative group together with architects and the rest of the team presented their conclusions on the needs of the dwellers and on the distribution of the private and communal spaces. A general strategy was to remove areas and functions from the private apartments and create bigger community spaces that could be enjoyed by everyone. As a result, 280 m2 of the total 2,950 m2 have been allocated for communal spaces, accounting for 10% of the entire built area. These spaces are placed around a central courtyard and include a community kitchen and dining room, a multipurpose room, a laundry room, a co-working space, two guest rooms, shared terraces, a small community garden, storage rooms, and bicycle parking. La Borda comprises 28 dwellings that are available in three different typologies of 40, 50 and 76 m2, catering to the needs of diverse households, including single adults, adult cohabitation, families, and single parents. The modular structure and grid system used in the construction of the dwellings offer the flexibility to modify their size in the future.

The construction of La Borda prioritized environmental sustainability and minimized embedded carbon. To achieve this, the foundation was laid as close to the surface as possible, with suspended flooring placed a meter above the ground to aid in insulation. Additionally, the building's structure utilized cross-laminated timber (CLT) from the second to the seventh floors, after the ground floor made of concrete. This choice of material had the advantage of being lightweight and low carbon. CLT was used for both the flooring and the foundation The construction prioritized the optimization of building solutions through the use of fewer materials to achieve the same purpose, while also incorporating recycled and recyclable materials and reusing waste. Furthermore, the cooperative used industrialized elements and applied waste management, separation, and monitoring. According to the members of the cooperative (LaCol, 2020b), an important element for minimizing the construction cost was the substitution of the underground parking, which was mandatory from the local legislation when you exceed a certain number of housing units, with overground parking for bicycles. La Borda was the first development that succeeded not only in being exempt from this legal requirement but also in convincing the municipality of Barcelona to change the legal framework so that new cooperative or social housing developments can obtain an “A” energy ranking without having to construct underground parking.

Energy performance goals focused on reducing energy demands through prioritizing passive strategies. This was pursued with the bioclimatic design of the building with the covered courtyard as an element that plays a central role, as it offers cross ventilation during the warm months and acts as a greenhouse during the cold months. Another passive strategy was enhanced insulation which exceeds the proposed regulation level. According to data that the cooperative published, the average energy consumption of electricity, DHW, and heating per square meter of La Borda’s dwellings is 20.25 kWh/m², which is 68% less, compared to a block of similar characteristics in the Mediterranean area, which is 62.61 kWh/m² (LaCol, 2020a). According to interviews with the residents, the building’s performance during the winter months is even better than what was predicted. Most of the apartments do not use the heating system, especially the ones that are facing south. However, the energy demands during the summer months are greater, as the passive cooling system is not very efficient due to the very high temperatures. Therefore, the group is now considering the installation of fans, air-conditioning, or an aerothermal installation that could provide a common solution for the whole building. Finally, the cooperative has recently installed solar panels to generate renewable energy.

Social impact and scalability

According to Cabré & Andrés (2018), La Borda was created in response to three contextual factors. Firstly, it was a reaction to the housing crisis which was particularly severe in Barcelona. Secondly, the emergence of cooperative movements focusing on affordable housing and social economies at that time drew attention to their importance in housing provision, both among citizens and policy-makers. Finally, the moment coincided with a strong neighbourhood movement around the urban renewal of the industrial site of Can Batlló. La Borda, as a bottom-up, self-initiated project, is not just an affordable housing cooperative but also an example of social innovation with multiple objectives beyond providing housing.

The group’s premise of a long-term leasehold was regarded as a novel way to tackle the housing crisis in Barcelona as well as a form of social innovation. The process that followed was innovative as the group had to co-create the project, which included the co-design and self-construction, the negotiation of the cession of land with the municipality, and the development of financial models for the project. Rather than being a niche project, the aim of La Borda is to promote integration with the neighbourhood. The creation of a committee to disseminate news and developments and the open days and lectures exemplify this mission. At the same time, they are actively aiming to scale up the model, offering support and knowledge to other groups. An example of this would be the two new cooperative housing projects set up by people that were on the waiting list for la Borda. Such actions lead to the creation of a strong network, where experiences and knowledge are shared, as well as resources.

The interest in alternative forms of access to housing has multiplied in recent years in Catalonia and as it is a relatively new phenomenon it is still in a process of experimentation. There are several support entities in the form of networks for the articulation of initiatives, intermediary organizations, or advisory platforms such as the cooperative Sostre Civic, the foundation La Dinamo, or initiatives such as the cooperative Ateneos, which were recently promoted by the government of Catalonia. These are also aimed at distributing knowledge and fostering a more inclusive and democratic cooperative housing movement. In the end, by fostering the community’s understanding of housing issues, and urban governance, and by seeking sustainable solutions, learning to resolve conflicts, negotiate and self-manage as well as developing mutual support networks and peer learning, these types of projects appear as both outcomes and as drivers of social transformation.

Alignment with project research areas

The project is relevant to RE-DWELL as it follows an innovative approach in relation to each of the three research areas: 1) Design, planning, and building, 2) Community participation and 3) Policy and financing.

In relation to “Design, planning and building”, one of the group's objectives was to promote a sustainable building model. The construction was designed in order to have a low environmental impact and to promote energy efficiency. The dwellers were involved in the decision-making of the building's energy performance, by evaluating their actions and living patterns. The building is understood as a totality made up of interrelated dwellings and households which demonstrates the importance of a more holistic vision, encompassing issues of social, environmental, and economic sustainability.

In relation to “Community participation", the project followed a robust participatory process throughout all the phases, from its initiation and research activities to decisions regarding the legal model, co-design of the building, final construction and management and maintenance. The project’s initiators used open assemblies as spaces for participation, where neighbours and local organisations could meet, exchange information, and make decisions together. Furthermore, the project fosters a community-oriented type of living, with common spaces, shared facilities, and a schedule for distributing everyday activities. The collectivisation of facilities and services fosters social values, such as mutual support. For example, residents share the tasks of childcare, preparing shared meals, gardening, cleaning of the common areas, and laundry equally among themselves. This creates a sense of community and encourages mutual aid and cooperation among the residents.

Finally, with regard to "Policy and Financing", the project developed an innovative housing plan for the provision of affordable housing, which led to legislative change and pushed for new policies. The "grant of use" model was used to separate the use-value from the exchange value of the property, thus preventing speculation and advocating for different types of ownership that are secure and affordable in the long-term. Following the success of La Borda, the municipality of Barcelona implemented the same model on seven other plots, extrapolating the experiment. The project also developed a unique funding model, demonstrating an innovative approach by securing funding from the credit cooperative Coop57, which offered an alternative solution and overcame the traditional barriers and downgrades of obtaining funding from mainstream banking systems. However, as the credit cooperative was only able to lend a limited amount, the remaining cost was covered by alternative sources of funding, such as participatory bonds and voluntary contributions to the "social capital fund," which is the share capital fund of the cooperative.

* This diagram is for illustrative purposes only based on the author’s interpretation of the above case study

Alignment with SDGs

La Borda seems to be aligned with the following sustainable development goals (UN, 2020):

Goal 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.

It has been manifested that there is a link between living in decent housing conditions and mental health and well-being. Intergenerational and communitarian housing schemes offer mutual support to their members, facilitating their everyday lives.

Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls

La Borda contributes to achieving this goal by recognizing and valuing the gender perspective and the work performed by women in the domestic space. The project aims to redistribute and collectivize everyday household activities, such as childcare, cooking, laundry, and others, which have traditionally been carried out by women. As a result, these activities are becoming more visible, taking place outside of private spaces, and being shared among all residents, providing opportunities for social interaction and community building.

Goal 7: Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all

One of the goals of La Borda was to follow a sustainable development model, prioritizing renewable energy sources, and thus minimizing carbon emissions. To pursue a more energy-efficient solution in the housing sector, La Borda cooperative initially attempted to retrofit an existing vacant building in Can Batlló. However, this plan was abandoned as it required more time for its realization and at that point, quicker solutions were needed. Energy efficiency was achieved, firstly, by lowering the demand for energy consumption through passive strategies (the use of the covered courtyard as a micro-climate element, enhanced insulation, etc.) and secondly by combining renewable energy resources, such as solar panels, with non-renewable ones. The choice of the building materials also took the carbon footprint into consideration and natural and low-energy materials such as wood, and recycled and recyclable products were prioritized.

Goal 10: Reduced inequality within and among countries

One of the principles of La Borda was to provide equal opportunities for accessing the cooperative to diverse individuals with varying needs that do not necessarily fit into traditional household typologies centered around the nuclear family structure. This was manifested in two ways. Firstly, by creating different typologies of housing units that can accommodate the needs of different household configurations. Secondly, a flexible modular structure was employed to offer the possibility of future modifications in case the needs of the inhabitants or the number of people change.

Goal 11: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable

La Borda aims to provide access to affordable, adequate, and secure housing with basic services through the active participation of the community. A way to evaluate the success of this goal could be to measure the proportion of households that left inadequate/ poorly served housing by moving into the housing cooperative.

Goal 12. Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns

To assess the achievement of this goal, one way could be to measure the reduction in energy consumption from non-renewable sources as a result of La Borda's sustainable design practices and use of low-emission materials.

Goal 16: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels

La Borda was a social experiment that achieved the promotion and legitimization of a novel framework for housing provision in the city of Barcelona. This framework led to a revision of municipal policies concerning building permissions and obligations.

References

Allen, J. (2006). Welfare regimes, welfare systems and housing in southern Europe. European Journal of Housing Policy, 6(3), 251–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616710600973102

Avilla-Royo, R., Jacoby, S., & Bilbao, I. (2021). The building as a home: Housing cooperatives in Barcelona. Buildings, 11(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/BUILDINGS11040137

Cabré, E., & Andrés, A. (2018). La Borda: a case study on the implementation of cooperative housing in Catalonia. International Journal of Housing Policy, 18(3), 412–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2017.1331591

Can Batlló. (2020). Can Batlló. https://canbatllo.org/can-batllo/

Girbés-Peco, S., Foraster, M. J., Mara, L. C., & Morlà-Folch, T. (2020). The role of the democratic organization in the La borda housing cooperative in Spain. Habitat International, 102. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HABITATINT.2020.102208

la Borda. (2020). Cesión de uso. http://www.laborda.coop/es/proyecto/cesion-de-uso/

LaCol. (2020a). Com de sostenible realment és la Borda? http://www.lacol.coop/actualitat/sostenible-realment-borda/

LaCol. (2020b). La Borda: visita arquitectònica. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YQYTrgeT7jY&ab_channel=Lacolarquitecturacooperativa

Parés, M., Ferreri, M., & Cabré, E. (2021). La coproducció d’habitatge a Catalunya: orientacions per al món local.

Related vocabulary

Affordability

Co-creation

Community Empowerment

Community-led Housing

Financial Wellbeing

Flexibility

Grant-of-use Cooperative Housing

Participatory Approaches

Social Sustainability

Spatial Agency

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 03-06-2022

Read more ->Area: Policy and financing

Created on 21-04-2023

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 16-02-2022

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 03-06-2022

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 05-10-2023

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 14-10-2024

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 19-06-2024

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 14-10-2024

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 17-02-2022

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 03-06-2022

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 30-01-2024

Read more ->Related publications

Tzika, Z., & Sentieri, C. (2022, February). Understanding co-creation in the transdisciplinary research of sustainable and affordable housing. Reinventing the City, Scientific conference AMS Institute, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Posted on 22-02-2026

Conference

Read more ->Tzika, Z., & Sentieri, C. (2023, June). Understanding community participation in cooperative housing using the capabilities approach. In European Network for Housing Research (ENHR) Conference 2023, Lodz, Poland.

Posted on 22-02-2026

Conference

Read more ->Tzika, Z., & Sentieri, C. (2023). Towards collective forms of dwelling: Analysis of the characteristics of the emerging grant-of-use housing cooperatives in Catalonia [Poster Presentation]. In 2nd Conference on Participatory Design. Transforming the City: Public Space & Environment, Inequalities & Democracy. Athens, Greece.

Posted on 22-02-2026

Conference

Read more ->Blogposts

Exploring the Panorama of Barcelona's Urban Commons and the Dynamic State Relationships

Posted on 22-01-2024

Secondments

Read more ->

Towards flexible and industrialised housing solutions

Posted on 24-02-2023

Secondments

Read more ->

Cooperative housing in Barcelona

Posted on 01-02-2023

Secondments

Read more ->

The discussion for the right to housing. ENHR, Barcelona 2022

Posted on 12-09-2022

Conferences, Reflections

Read more ->