The Social Climate Fund: Materialising Just Transition Principles?

Created on 22-05-2023 | Updated on 11-07-2023

The EU's Social Climate Fund (SCF) is a part of the Green Deal initiative and aims to mitigate the financial impact of increased energy costs and gasoline prices resulting from extending the Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) to buildings and transport. The SCF will provide resources to assist vulnerable households, micro-enterprises, and transport users. It will operate from 2026 to 2032 and will be funded through revenues generated by the new ETS, with a maximum allocation of 65 billion euros, supplemented by national contributions. Many NGOs commend the SCF for incorporating a social dimension into EU climate policies and striving to ‘materialise’ the just transition. Nevertheless, concerns remain regarding the fund's size, tight timeframe, and limited stakeholder participation outlined in the proposed regulation.

Instrument

Fund

Issued (year)

2023

Application period (years)

2026-2032

Scope

European

Target group

European households at risk of energy and/or transport poverty

Housing tenure

Mixed

Discipline

Public policy

Object of study

Instrument

Description

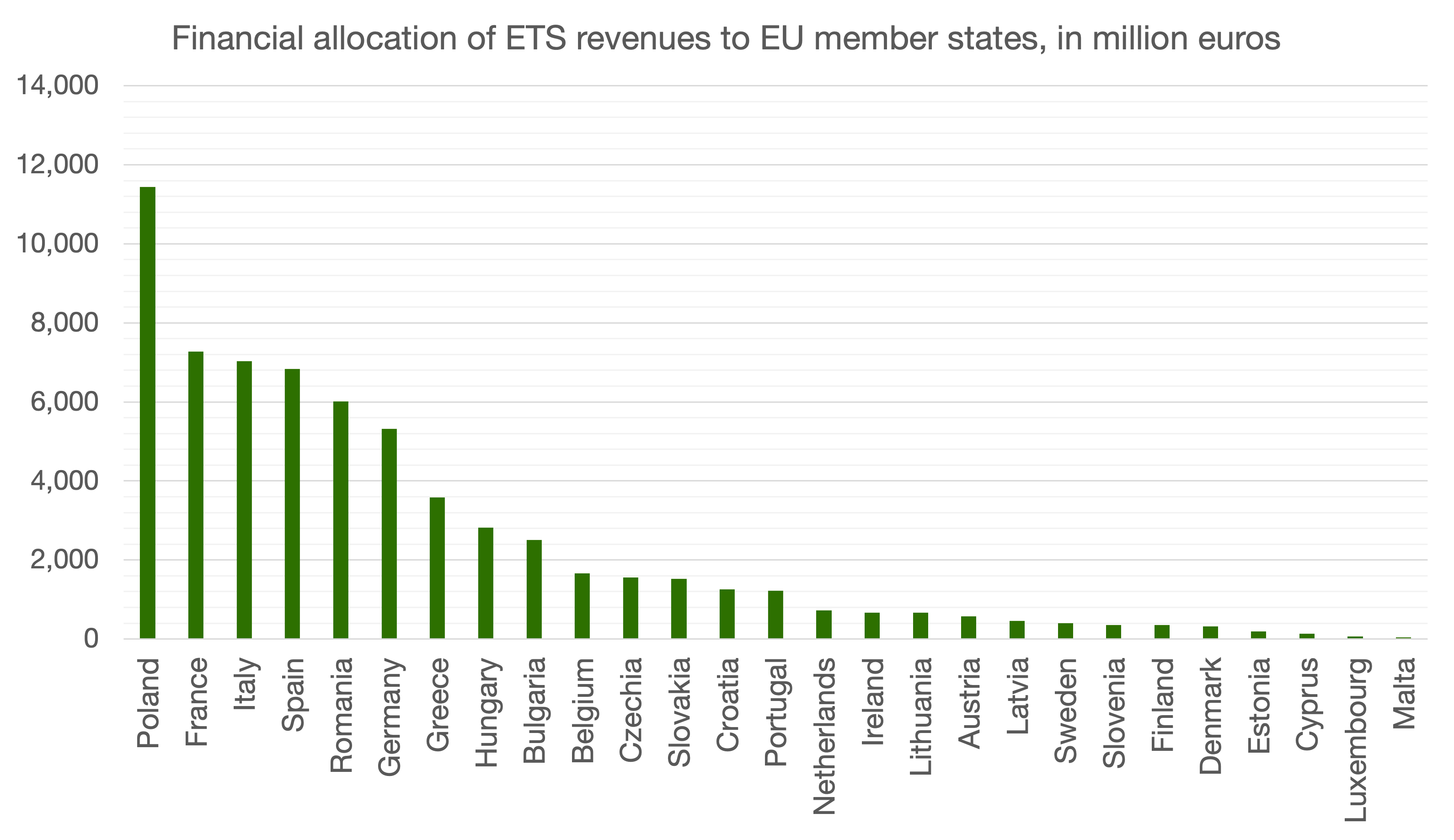

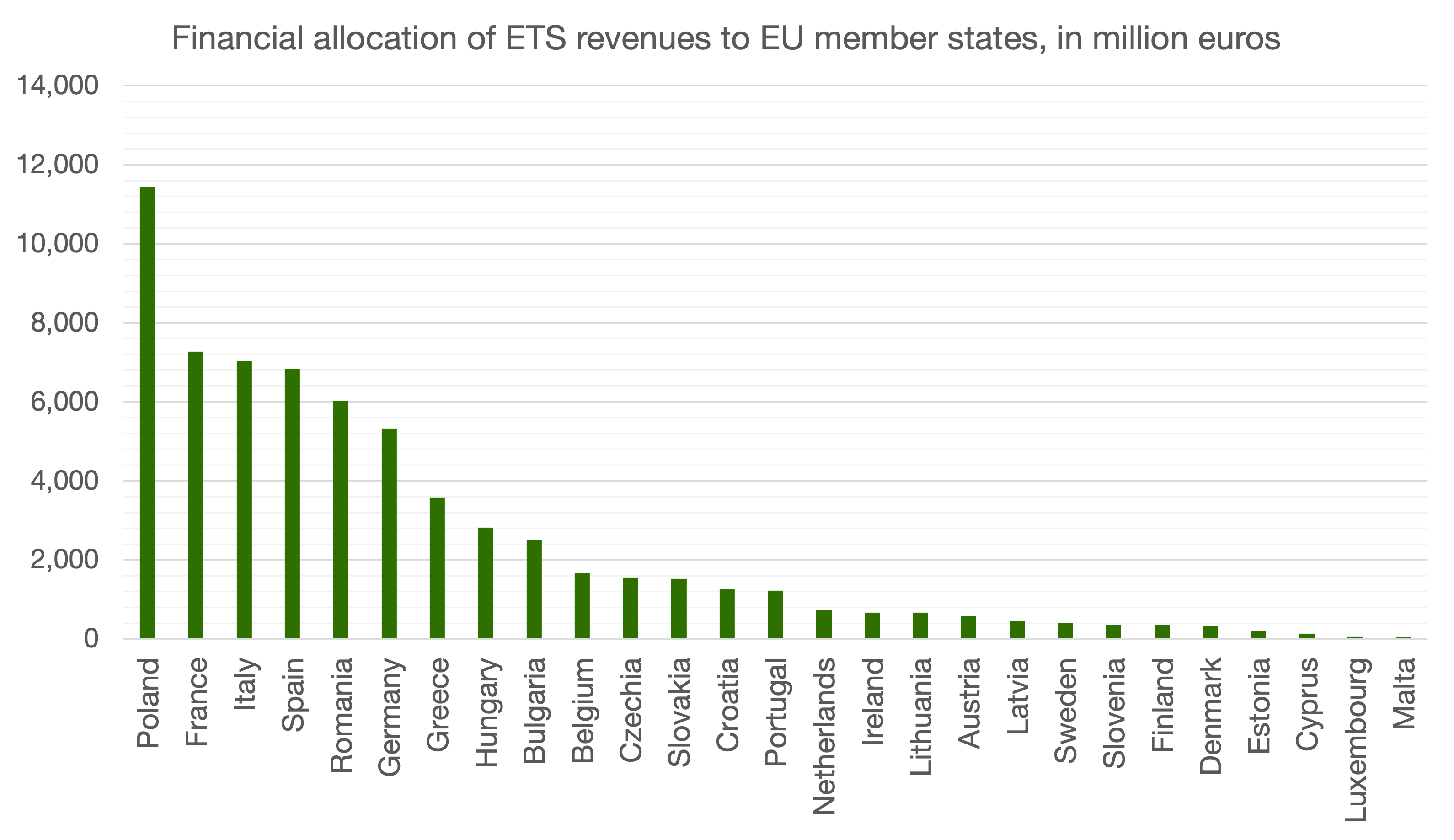

The EU's Social Climate Fund (SCF) was officially approved by the European Parliament on 18 April 2023 as part of the broader Green Deal initiative, which seeks to expand the scope of the Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) to encompass buildings, transport and other sectors. This extension of the ETS is expected to result in increased energy costs and gasoline prices for households and businesses. To assist vulnerable households, micro-enterprises, and transport users in mitigating the financial impact of these price increases, EU Member States may use resources from the SCF to finance various measures and investments. The SCF will primarily be funded through the revenues generated by the new emissions trading system, with a maximum allocation of €65 bn, which will be supplemented by national contributions. Temporarily established for the period of 2026-2032, the fund aims to provide support during this specified timeframe.

Preliminary Exploration of Merits and Limitations

The initiation of the SCF has received praise from various NGOs advocating for a just transition (WWF, 2022). Supporters highlight its significance in integrating a social dimension into EU climate policies, despite some remaining weaknesses. The SCF’s spending rules are commended for striking a suitable balance between financing structural investments and providing temporary direct income support to vulnerable households. Through the SCF, Member States can finance subsidies that will enable these households to renovate their homes, adopt energy-efficient technologies, and access renewable energy and sustainable transportation. Moreover, various NGOs welcome the requirement for government consultation with subnational administrations and civil society organizations. This could potentially facilitate greater engagement of the target groups in the legislative process. Notably, the SCF also introduces a definition of transport poverty, marking a first in EU policy, and aiding member states to identify those eligible for support (thereby improving recognitional justice).

Regarding the aforementioned weaknesses, there is a range of concerns. Firstly, the projected timeline may pose a limitation. Initiating green investments for vulnerable households only a year before the introduction of carbon pricing may not allow sufficient time for the desired impact. Projects related to energy renovation and improved public mobility infrastructure typically require several years to yield tangible results. Additionally, while Member States are required to include consultation with various stakeholders in their national ‘Social Climate Plans’ (SCPs), the level of participation outlined in the proposed regulation is minimalistic, raising concerns about ensuring procedural justice.

Perceived Importance of Targeting

The legislative text (EU, 2023) underscores the significance of consistent targeting, and Member States are required to furnish comprehensive information regarding the objective of the measure or investment and the specific individuals or groups it aims to address. Additionally, the European Commission expects an elucidation of how the measure or investment will effectively contribute to the accomplishment of the Fund's objectives and its potential to reduce dependence on fossil fuels.

Targeting is deemed particularly crucial with regard to direct income support, as universal energy support tends to generate inflationary pressures, encourage unsustainable behaviour, and yield regressive effects. The legislative text states that is crucial to perceive such support as a temporary measure accompanying the decarbonisation of the housing and transport sectors, rather than a permanent solution that fails to address the fundamental causes of energy poverty and transport poverty. Thus, this support should exclusively target the direct consequences of including greenhouse gas emissions from buildings and road transport under the purview of Directive 2003/87/EC, without encompassing electricity or heating costs related to power and heat production covered by the same directive. As stated, "recipients of direct income support should be targeted, as members of a general group of recipients, by measures and investments aimed at effectively lifting those recipients out of energy poverty and transport poverty" (EU, 2023: p.4).

The share of the SCF designated for renovation projects should also be specifically directed at the vulnerable households and transport users who are already receiving direct income support. SCPs are allowed to extend support to both public and private entities, including social housing providers and public-private cooperatives, in developing and providing affordable energy efficiency solutions and suitable funding mechanisms that align with the social objectives of the Fund. This support could include ‘financial assistance’ or even ‘fiscal incentives’, which poses the question of how lenient should the approach of the European Commission be towards the state support of social housing organisations, given the tensions that have emerged in the past (Gruis & Elsinga, 2014).

Ex Ante and Ex Post Assessment of Social Climate Plans

EU Member States are required to submit national Social Climate Plans (SCPs) no later than 30 June 2025, so that they can be given “careful and timely consideration”. The plans should encompass an investment component that promotes the long-term solution of reducing reliance on fossil fuels, potentially incorporating additional measures, such as temporary direct income support, to alleviate any immediate adverse effects on income.

The primary objectives of these plans must be twofold. Firstly, they should provide vulnerable households, vulnerable micro-enterprises, and vulnerable transport users with the necessary resources to enable them to finance and undertake investments in energy efficiency, the decarbonisation of heating and cooling systems, the adoption of zero- and low-emission vehicles, and sustainable mobility. This support may be provided through mechanisms such as vouchers, subsidies, or zero-interest loans. Secondly, the plans should mitigate the impact of rising fossil fuel costs on the most vulnerable segments of society, thus fighting energy poverty and transport poverty during the transitional phase until the aforementioned investments have been implemented.

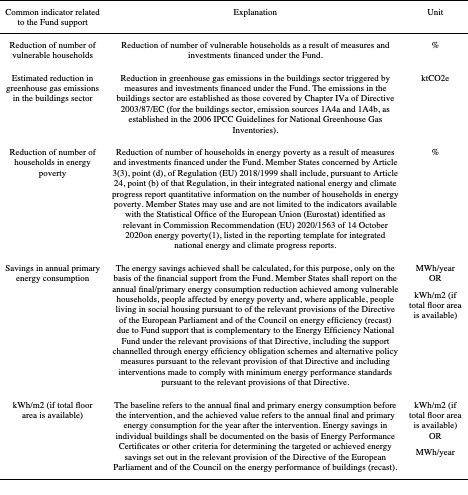

The legislative text contains comprehensive information concerning the criteria utilised to assess the SCPs upon submission and evaluation after implementation. The set of ‘result indicators’ that are specifically relevant to the 'building sector' can be found in the table accompanying this case study. Time will tell whether this framework is sufficient to ensure that besides ‘recognitional justice’ and ‘procedural justice’, the SCF will make sure that the European Green Deal delivers ‘distributive justice’.

Alignment with project research areas

The SCF is particularly relevant in RE-DWELL’s research framework, as it addresses housing affordability within the energy transition, with a specific focus on vulnerable groups. The SCF aims to provide resources to finance investments in energy efficiency and the decarbonisation of heating and cooling systems. Through the fund, Member States can finance subsidies or guarantee low-interest loans to enable vulnerable households or their (social) landlords to renovate their homes and adopt energy-efficient technologies.

The SCF is primarily funded through revenues generated by the new emissions trading system, with a maximum allocation of €65 bn, which may be supplemented by national contributions. This demonstrates the interplay of governance, market mechanisms, and financing in implementing the fund. Additionally, the text mentions the importance of assessing SCPs both ex ante and ex post, indicating a focus on evaluating the effectiveness of governance structures and financing mechanisms in achieving the fund's objectives.

* This diagram is for illustrative purposes only based on the author’s interpretation of the above case study

Alignment with SDGs

Overall, the Social Climate Fund contributes to several SDGs, five of which are explained below.

SDG 1: No Poverty

The SCF highlights the objective of mitigating the impact of rising fossil fuel costs on vulnerable segments of society, fighting energy poverty and transport poverty. This aligns with the goal of eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions.

SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy

The initiatives described in the text aim to promote energy efficiency, the decarbonisation of heating and cooling systems, and the adoption of zero- and low-emission vehicles. This contributes to the goal of ensuring access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all.

SDG 13: Climate Action

The EU's Social Climate Fund and the broader Green Deal initiative seek to address climate change by expanding the scope of the Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) to various sectors, including buildings and transport. The aim is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, promote renewable energy, and mitigate the financial impact on vulnerable groups. This aligns with the goal of taking urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.

SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities

The emphasis on targeting vulnerable households, micro-enterprises, and transport users for support, as well as involving subnational administrations and civil society organizations in decision-making processes, aligns with the objective of reducing inequalities within and among countries.

SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals

The requirement for government consultation and collaboration with subnational administrations and civil society organizations in the development of SCPs demonstrates a commitment to partnerships and multi-stakeholder engagement in achieving the SDGs. It reflects the importance of collaborative efforts between governments, private entities, and civil society to address climate challenges.

References

EU. (2023). Regulation (EU) 2023/955 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 May 2023 establishing a Social Climate Fund and amending Regulation (EU) 2021/1060. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32023R0955

Gruis, V., & Elsinga, M. (2014). Tensions between social housing and EU market regulations. European State Aid Law Quarterly, 13(3), 463-469.

WWF. (2022). Openletter: NGOs urge Council to agree on a comprehensive, bold and transformative Social Climate Fund. https://www.wwf.eu/?6937841/Implementing-a-Social-Climate-Fund-that-works-for-the-people-and-the-planet

Related vocabulary

Housing Affordability

Just Transition

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 17-10-2023

Read more ->Area: Policy and financing

Created on 03-06-2022

Read more ->Blogposts

Greater than the sum of its parts

Posted on 21-07-2021

Workshops

Read more ->