Aya Elghandour

ESR4

Aya has worked as an architect in Egypt and Portugal. Currently, she is a pre-doctoral researcher at the University of Sheffield, School of Architecture, UK. Meanwhile, she is an Early-Stage Researcher (ESR 4) for the Re-Dwell Research Project on Sustainable and Affordable Housing in Europe funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant.

She started her career in academia right after obtaining her BSc from the Architecture and Urban Planning Department at the Port Said University (PSU) in Egypt. During her master's studies, she investigated the computational design and optimization techniques to support decision-making using performance-based parametric design strategies to promote buildings sustainability. She published and presented her thesis case study in the Building Simulation and Optimization Conference (BSO) 2016 in Newcastle University, UK. After her MSc, she was promoted to be a teaching assistant for undergraduate courses that included designing housing projects and residential neighbourhoods.

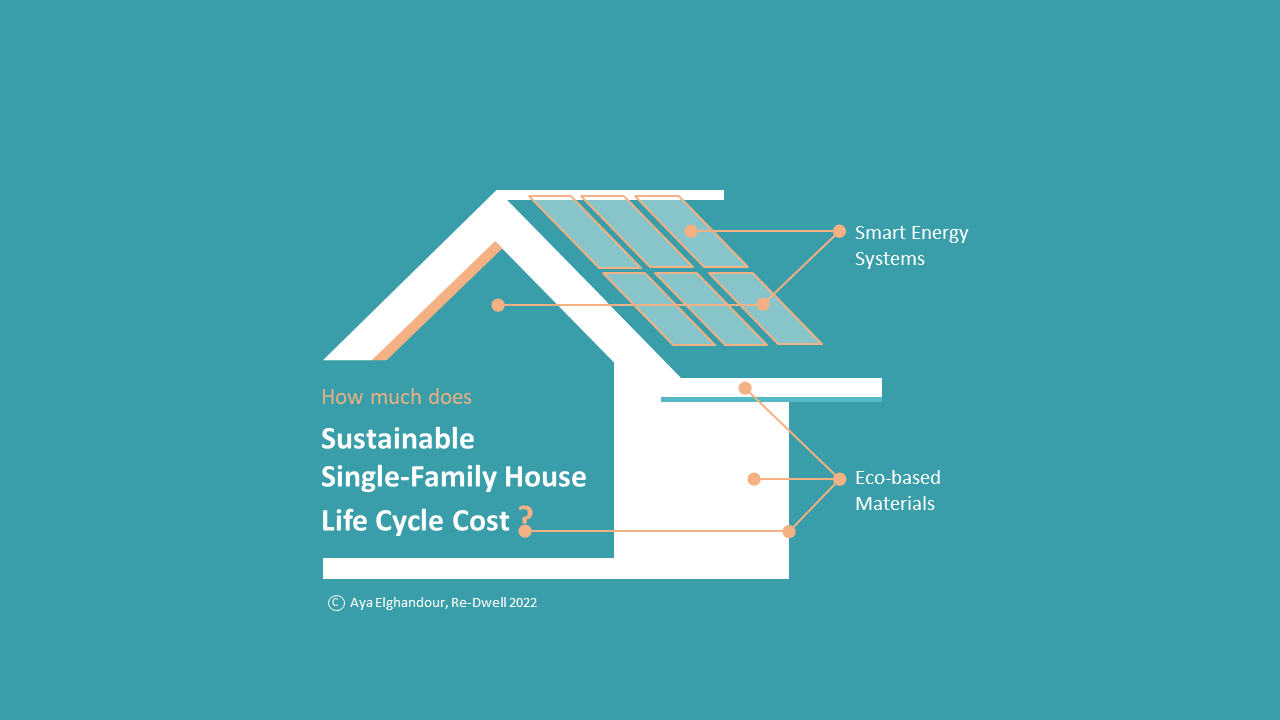

As an architect, she started constructing her professional experience since being an undergraduate in Egypt. She developed her strong conceptual and technical design experience in the industry from being involved in several projects including residence, social buildings, and landscape for public spaces. In Portugal, she joined an AEC company based in Lisbon, where she built a substantial experience in Building Information Modelling (BIM) for schematic design and execution of housing, commercial and industrial building projects in Portugal and Australia. Moreover, she experimented BIM parametric techniques to facilitate design workflow and multidisciplinary teamwork. Therefore, her current research interest aims to further investigate BIM strategies to conduct Lifecycle Cost Analysis (LCCA) to support housing sustainability and affordability.

August, 06, 2023

May, 18, 2022

September, 15, 2021

An Integrated Households' Health and Financial Wellbeing Life Cycle Costing Framework for the Design of Affordable Houses

The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes the significant impact of house conditions on human health and wellbeing (H+W). Addressing poor houses conditions in England could save the National Health Service over £1 billion annually where excess cold and falls on stairs result in the most expensive implications. Risks of health inequalities also exacerbate when houses are considered affordable regardless of their condition of being cold and expensive to heat in winter, overheating in summer, or lacking proper ventilation leading to dampness and mold. Such conditions reflect poor building performance and signal the need to prioritize households' H+W, starting from the design stages of affordable houses. Decisions made during these stages significantly affect future costs, including running and maintenance expenses to be paid by households, as well as building performance impacting their health (physical and mental). The study advocates rethinking the concept of affordable housing from design stages to ensure it is designed and constructed to be affordable for both households' H+W and housing providers as an investment in the long-term.

This study aims to develop Life Cycle Costing (LCC) framework, integrating households' H+W considerations during the design stages of affordable houses. The study adopts a transdisciplinary approach and involves a secondment in a non-academic environment of a British housing association to understand housing providers' perspectives. Semi-structured interviews with professionals from various regions in England, covering architecture, affordable housing provision, and public health, will be conducted. A taxonomy of tangible components contributing to H+W within a house will be established. Subsequently, the H+WLCC framework will be proposed and tested using a case study analysis of two design scenarios of a real house in Sheffield. The detailed house modeling will use Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Building Performance Simulation (BPS) to predict its future indoor environmental performance and energy efficiency. The first scenario will be validated by comparing it with real data from the real house, while the second will involve changes in variables of materials (e.g insulation and window type) and energy and ventilation systems.

The expected outcome is a novel H+W LCC framework tailored to the British context, adaptable to other European countries. This framework will serve as a valuable decision-making tool for designing affordable and healthy houses, considering perspectives from both housing providers and households. Additionally, it will identify key stakeholders whose decisions influence the house impact on households' H+W. The framework will offer valuable guidance, considering not only initial construction and operational costs concerning housing providers but also the long-term implications for households' health and financial wellbeing. The study advocates rethinking the concept of affordable housing to ensure it is designed and constructed to be affordable for both households' H+W and housing providers as an investment.

An integrated LCC framework for households’ health and wellbeing

Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) decisions in the design development stages can influence up to 80% of the future costs of a building. Therefore, life cycle cost analysis (LCCA) is one of the most effective methods to select economically sustainable solutions while responding to environmental measures. In the context of sustainable housing design, research and public policies are giving more attention to economic and environmental concerns. Less consideration is given to the financial and psychological burdens on their households which strongly correlate with their health and wellbeing.

In this regard, there are two major problems. The first is estimating monetary expenses paid by residents are often excluded from housing LCCA. The second, design features that lead to reducing construction and maintenance costs are often prioritized over the solutions that would better contribute to households’ health and wellbeing such as daylight availability, noise prevention and more.

Therefore, this research aims to develop a framework that integrates households’ health and wellbeing into life cycle cost analysis for the design of social housing. This framework aims to bring residents health and wellbeing at the forefront of AEC decision-making while identifying cost effective solutions for housing stakeholders while responding to building performance requirements. The framework will be constructed using Building Information Modelling (BIM) processes that allow storing and sharing all building geometric and non-geometric data in a digital platform among various stakeholders.

Reference documents

Life Cycle Economic and Social Cost-based Design

Housing affordability and housing quality are two key facets that influence social housing provision. The first is concerned with the overall cost of having and maintaining a house without adding unwanted financial pressure which may lead to psychological burdens on households. On the other hand, housing quality is pertinent to providing a pleasant, healthy, durable, and safe indoor and outdoor built environment, which in return raises housing costs. In this respect to measuring housing affordability, Life Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA) can be used as an economic analysis method to estimate the overall cost of building alternatives starting from the design, construction, operation, till its disposal phase. Therefore, housing alternatives with the lowest overall cost, and in line with quality, can be identified from early design stages where the most influential building decisions are made.

While LCCA is crucial in selecting the optimum housing alternative, it, however, increases the design complexity. For instance, estimating energy consumption, which occupies the largest portion of buildings' LCC, involves the use of various computational tools and requires reliable data that might not be available. In addition, from a social perspective, assessing housing quality and its LCC based on post-occupancy social feedback is still limited. Accordingly, there is a real need to transform occupants’ feedback and their potential role in energy saving into useful data to support design teams. In practice, Building Information Modelling (BIM) allows storing and managing all building data in a single platform. Thus, it has the potential of conducting LCCA and accessing real-time data from completed buildings. However, there is a present lag in providing an applicable feedback loop to inform design teams with this reliable data. Moreover, there is a dearth of research that integrates LCCA and social dimensions into BIM.

Therefore, my research aims to develop a market-friendly framework that achieves this integration to reduce the total LCC and inform the design based on occupants’ real needs. The study will adopt a mixed approach of quantitative and qualitative research methods. A taxonomy of literature will be conducted to explore LCCA and social assessment methodologies, parameters, and optimization goals that are adequate for BIM to inform the design of the framework. This framework will be developed following four phases of fieldwork consisting of surveys, interviews, a co-design event with stakeholders and residents, as well as simulation-based comparative analysis of real social housing case studies. As a result, the study will be able to classify and prioritize the most efficient data to be utilized for BIM models. Finally, the framework applicability will be tested for a social housing unit. Therefore, the study is expected to enable informed economic and social-based decision-making from early design stages using BIM to promote housing sustainability and improve affordability.

A Transdisciplinary Peek Behind Secondment Scenes & Common Challenges to Housing Associations in England

Posted on 22-10-2023

Secondments, Reflections

Read more ->

A Culture of a British Housing Association

Posted on 20-07-2023

Secondments

Read more ->What does 'Being Humble!' have to do with affordable and sustainable housing?

Posted on 19-04-2023

Workshops, Secondments, Reflections

Read more ->

A Turning Point Conversation on Portuguese Public Dwellings Design, Is it some kind of Feminism?

Posted on 06-09-2022

Secondments

Read more ->

We might think we are helping, but [Through Sustainability Lens] we might not!

Posted on 05-10-2021

Workshops, Reflections

Read more ->

Kick-off a sense of unity out of us being different!

Posted on 15-07-2021

Workshops

Read more ->

Dalarnas Villa - Built Research Project Investigating Sustainability

Created on 21-10-2024

Pre-1919 Niddrie Road Retrofit – An Example of Care for Climate and Health

Created on 15-11-2024

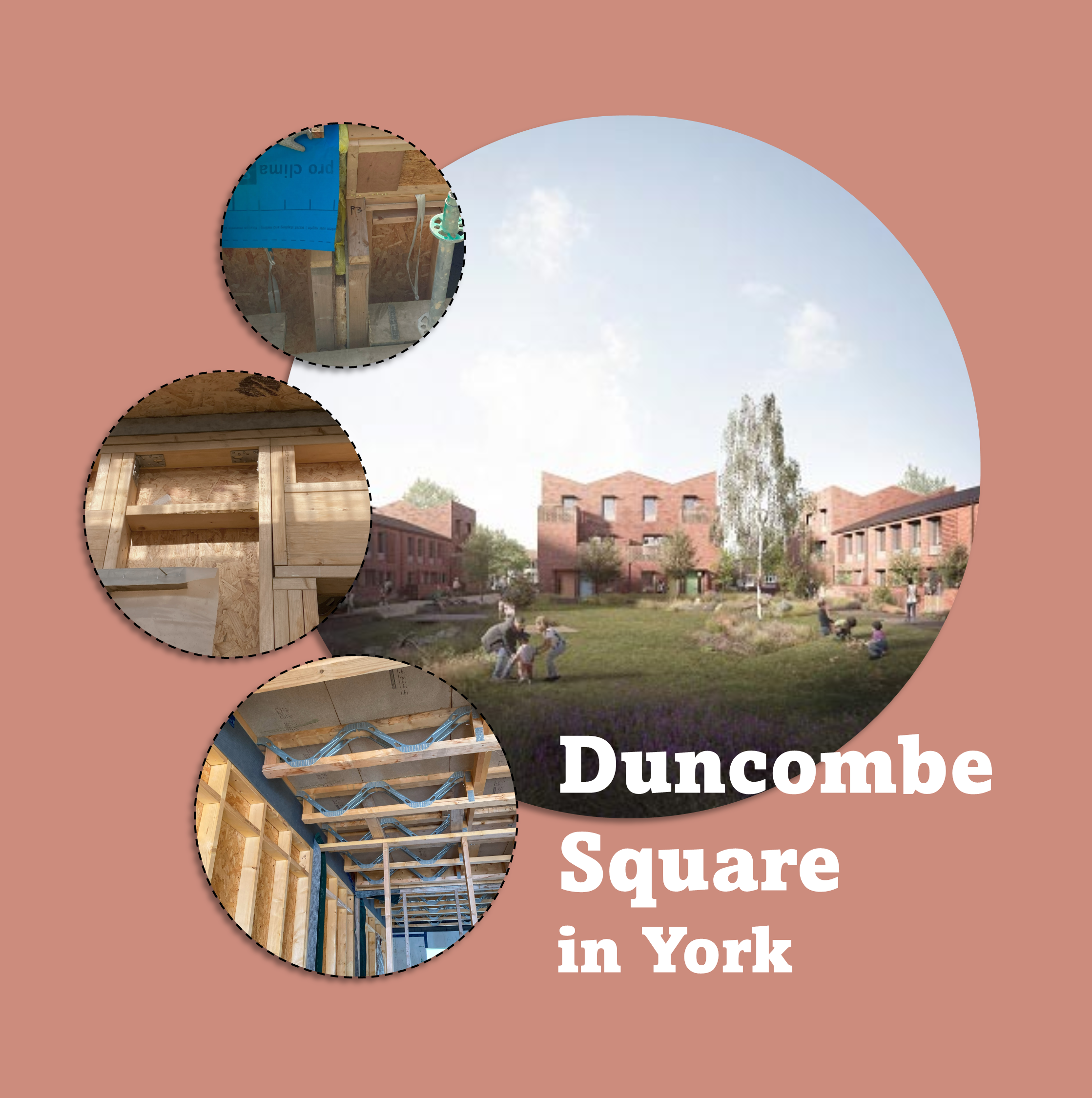

York's Duncombe Square Housing: Towards Affordability, Sustainability, and Healthier Living

Created on 15-11-2024

BIM

Financial Wellbeing

Housing Affordability

Housing Quality

Life Cycle Costing

Measuring Housing Affordability

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 16-02-2022

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 14-10-2024

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 17-10-2023

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 14-10-2024

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 05-12-2022

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 17-10-2023

Read more ->