Navigating Two Realms: A Comparative Exploration of Community-Engaged Architectural Education in Spain and the UK

Posted on 04-12-2023

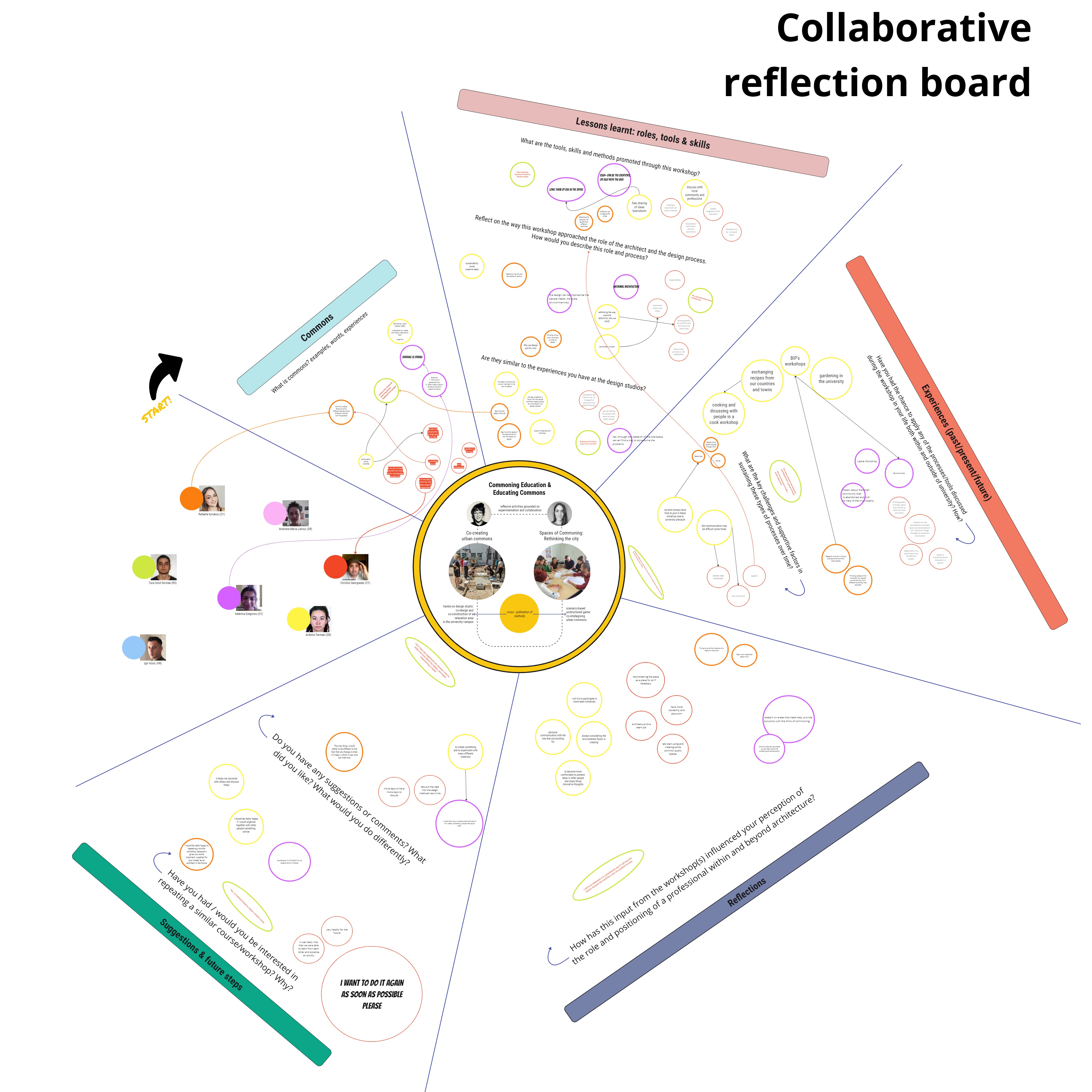

Embarking on two distinct secondments—one in the vibrant city of Valencia, Spain, from October to December 2022, and the other in heart of Sheffield, UK, from late September to late November 2023—provided me with a unique opportunity to delve into the realms of community-engaged architectural education. Each experience not only offered insights into the diverse approaches of two renowned institutions, the Polytechnic University of Valencia and the Sheffield School of Architecture, but also shed light on the nuances that exist when navigating language barriers and cultural disparities.

Spain: Bridging the Language Gap

My first secondment in the Polytechnic University of Valencia presented an initial challenge: a language barrier that I had yet to conquer. My rather non-existent proficiency in Spanish restricted my direct engagement with students, but it did not hinder my ability to observe the innovative pedagogical methods employed by the institution.

During my time in Valencia, I witnessed a series of exercises designed to cultivate creativity and empathy among students. These exercises pushed boundaries, encouraging students to think beyond conventional architectural norms. Despite the linguistic challenges, I was able to appreciate the universality of architectural exploration as a means of fostering innovation and expanding students' perspectives.

One noteworthy initiative was the participatory design & build activity, "JugaPatraix." Collaborating with the local architectural practice FentEstudi, students engaged in creating small-scale, acupuncture interventions in the Patraix neighbourhood. Drawing inspiration from the unobstructed exploration of toddlers in urban surroundings, these interventions transformed the streets into playful landscapes. The project demonstrated that, with enthusiasm and a modest budget, transformative architectural endeavours can thrive, transcending language barriers.

UK: The Dynamics of Mentorship in Sheffield

In Sheffield, my second secondment involved shadowing the "Live Projects" studio—a powerhouse within the Sheffield School of Architecture. Often referred to as the juggernaut of the Architecture School, Live Projects operates as a student-led studio that has built a reputation extending beyond city borders.

A notable distinction was the choice of nomenclature; the term "mentor" took precedence over "tutor." This seemingly subtle shift in language encapsulated the essence of the Live Projects studio. Here, teaching staff assumed a guiding role, providing support when necessary, as opposed to the conventional tutorship that typically directs the entire process. This departure from the traditional model showcased a student-centric approach, emphasizing autonomy and self-direction.

Comparative Reflections

Both experiences offered invaluable insights into the multifaceted world of community-engaged architectural education. Despite the contrasting contexts, a common thread emerged: the importance of fostering creativity, empathy, and innovation within architectural pedagogy.

In Spain, the emphasis on unconventional exercises and participatory design highlighted the potential for transformative architectural interventions, even in the face of language barriers. The JugaPatraix project exemplified how collaborative efforts, driven by a shared passion, can reshape urban landscapes on a tight budget.

On the other hand, the Live Projects studio in Sheffield showcased the power of student-led initiatives and the significance of mentorship over traditional tutoring. The dynamic, boundary-crossing reputation of Live Projects underscored the impact that a student-centric model can have, transcending institutional and national boundaries.

Conclusion

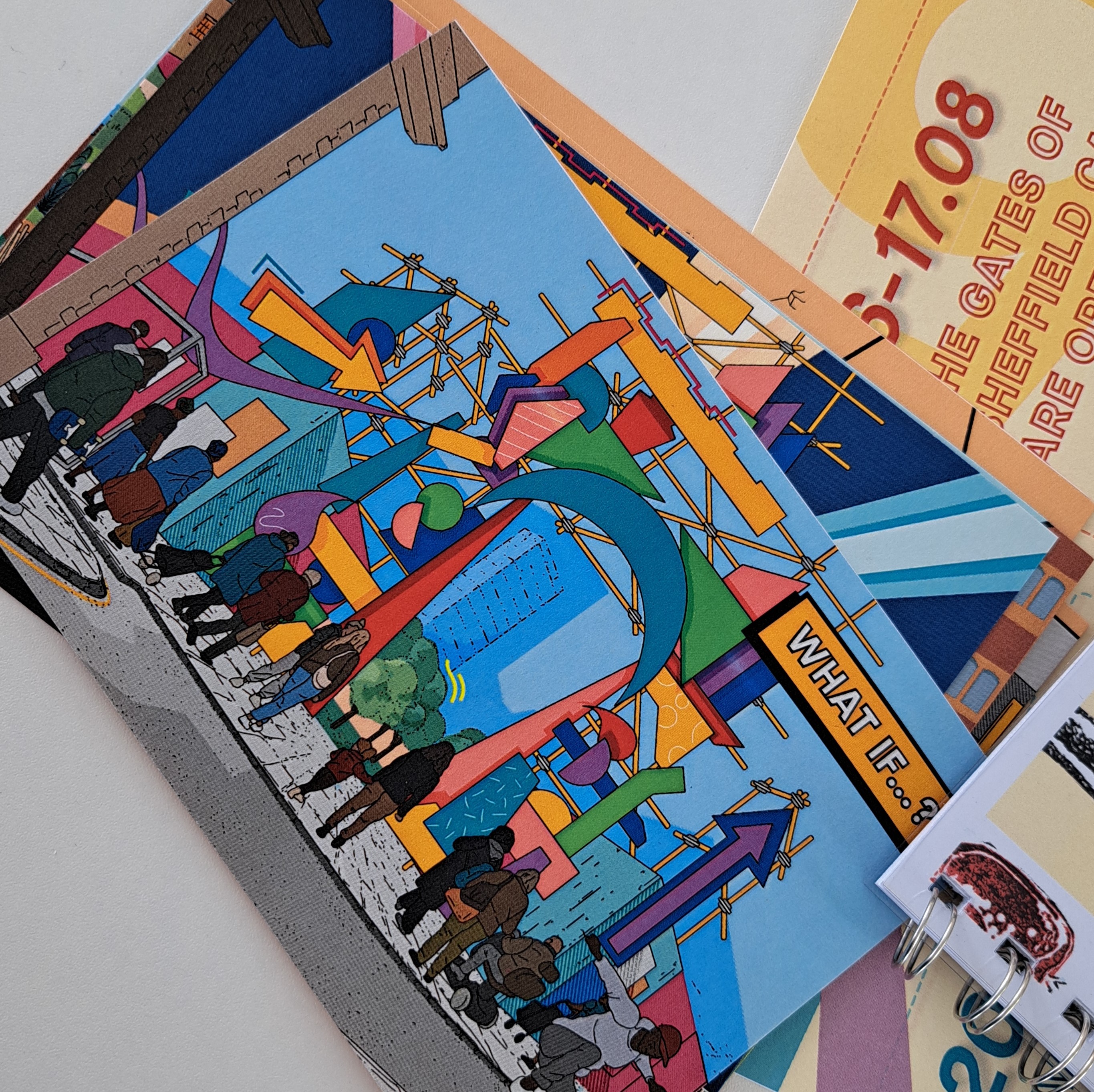

In retrospect, these secondments were more than a mere exploration of architectural education—they were windows into the dynamic intersection of culture, language, and pedagogy. The experiences in Spain and the UK illuminated the universal capacity of architecture to transcend barriers and foster transformative change. As I reflect on these enriching experiences, I am immensely grateful for the insights gained, the lessons learned, and the enduring impact on my perspective as a participant both in the global discourse of architectural education and in the local context of the University of Cyprus. As I move on to the next phase of my fieldwork, all the questions I carry forward with me begin with the same two words: What if...?

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my co-supervisor, Carla Sentieri for making my stay at UPV as fruitful as possible, and Míriam Rodríguez and Fran Azorín Chico (members of FentEstudi) that allowed me to tag along, ask questions and observe their activities. Then, I would like to thank Karim Hadjri and Krzysztof Nawratek at Sheffield School of Architecture for facilitating all the paperwork as well as Carolyn Butterworth, Daniel Jary and Sam Brown for being more eager to help me out that I would have ever hoped for, Finally, a big thank you to my colleagues Aya Elghandour and Mahmoud Alsaeed for making my stay in Sheffield memorable within and beyond the confines of the Architecture School.

Author:

E.Roussou

(ESR9)