North Wingfield Road social housing complex.

Created on 17-05-2022 | Updated on 25-11-2022

The North Wingfield Road social housing complex consists of 11 similar affordable family houses developed on a rural exemption site within the Derbyshire Green Belt at the eastern edge of the village of Grassmoor, Derbyshire, England. The design of the project drew inspiration from the surrounding rural environment, especially farmsteads and crew yards – clusters of buildings around large farm buildings – which are an essential feature of the local identity. Homes, amenities and landscaping are organised around the central common space to create a friendly environment that provides a sense of containment, safety and immersion in the surrounding natural landscape.

Through its energy efficiency rating (energy performance certification rating B, with a potential to be A), responsible use of material and reduced impact on the surrounding natural environment, a maximum score of 12 green points was given to the development in its Building for Life 12 assessment. In 2021, it received the Housing Design Awards (a UK-based competition) in recognition of good practice in social housing development.

Architect(s)

DK-Architects

Location

Grassmoor, Derbyshire, East Midlands, England, United Kingdom (53°12'13.40"N, 1°23'59.64"W).

Project (year)

July-2014

Construction (year)

February, 2020

Housing type

multifamily housing (Semi-detached house)

Urban context

suburb

Construction system

Timber frame

Status

Built

Description

a) Design philosophy

According to the Housing Design Awards, the design of the North Wingfield project took a contemporary design approach, combining the features of local vernacular architecture - as adopted from local farms - with the developer's vision and requirements for flexible, sustainable and innovative housing (HDA, 2021). The architectural office DK -Architects explains that this fusion is represented by massing the morphology of the project, traditional architectural elements (e.g. Dreadnought brick (roof), Janinhoff brick (walls)) with modern elements such as large glazing and aluminium cladding. This combination of materials not only provides an aesthetically pleasing appearance, but also helps to capture heat, ultimately reducing heating energy consumption for at least seven months of the year (DK-A, 2021). In addition, several innovative features have been adapted, including the well-planned use of space and the clear conceptual plans that extends beyond the interior spaces to the shared courtyard, which serves as a social gathering place for the tenants.

The inspiration for the courtyard was derived from the local identity, the farmstead and the crew yard (HDA, 2021). At the same time, the use of a see-through fence, which extends the sightline into the rural surroundings, provides a calming splash of green colour in each residential unit. The semi-raised upper massing extends the courtyard and provides a semi-enclosed space that enhances the feeling of safety and security (DK-A, 2021). Meanwhile, the buildings in the front row clearly stand out from the surrounding buildings through the use of colours and materials and also serve as an entrance gate to the project (DK-A, 2021; HDA, 2021). Each dwelling has its own mini agricultural space, which has proven valuable for the well-being of the residents.

b) Construction process

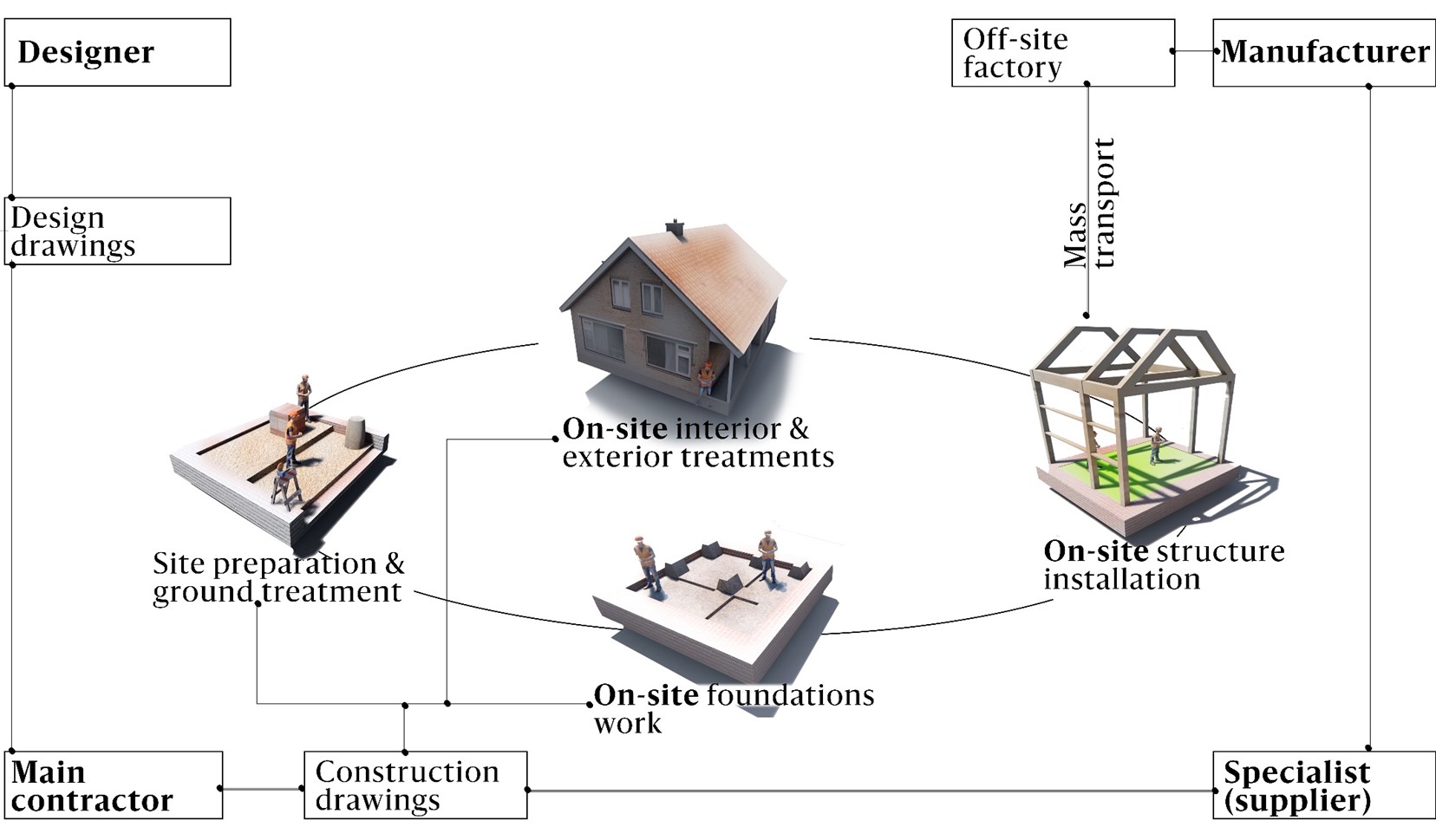

The skeleton of the building utilises an off-site timber frame method of construction, adopting a semi-modular design principle (Davies & Jokiniemi, 2008). This construction method provides a structure with a superior thermal envelope that requires minimal maintenance and is a 'fit-and-forget' solution for the lifetime of the building. In addition, both labour and material costs were significantly reduced due to less reliance on craftsmanship and multiple suppliers. This is in line with the UK government plans to revamp construction regulations to encourage bold, creative and sustainable construction methods (Davies & Jokiniemi, 2008; Sterjova, 2017).

The construction process started with ground treatment, followed by the casting of the foundations on site. Meanwhile, the timber frames were manufactured off-site at the supplier's factory, which helped to reduce construction work and thus carbon emissions. The frames were then transported to the site for fixing and external treatment, and all the construction work ran in parallel (Wheatley, 2020). The overall process can be seen in Figure 1.

c) Sustainability integration

At the sustainability level, the project worked on several areas to maximise the adaptation of sustainability features and minimise the impact on the natural environment (HDA, 2021).

Creating sustainable buildings

- Through sustainable design and layout (e.g. orientation, maximising daylight, optimising solar gain).

- Creating high quality outdoor environments (e.g. public and private open spaces that provide shade and shelter and consider flood retention and multi-functional green spaces to protect wildlife).

- Use of sustainable water management techniques (e.g. use of sustainable drainage systems and consideration of surface water run-off).

- Use of sustainable waste management facilities for private and communal use (through the appropriate provision of waste and recycling bins).

- Focus on reducing the use of non-renewable energy.

Reduction of carbon emissions

- The project has been designed in accordance with the highest level of building regulations and sustainability standards, in line with the Government's 10-year timetable for all new homes to be carbon neutral by 2016.

- Water recycling techniques (such as grey water and rainwater harvesting).

- Sustainable Transport (reducing reliance on the private car, incorporating practical and accessible sustainable transport patterns).

d) Energy performance

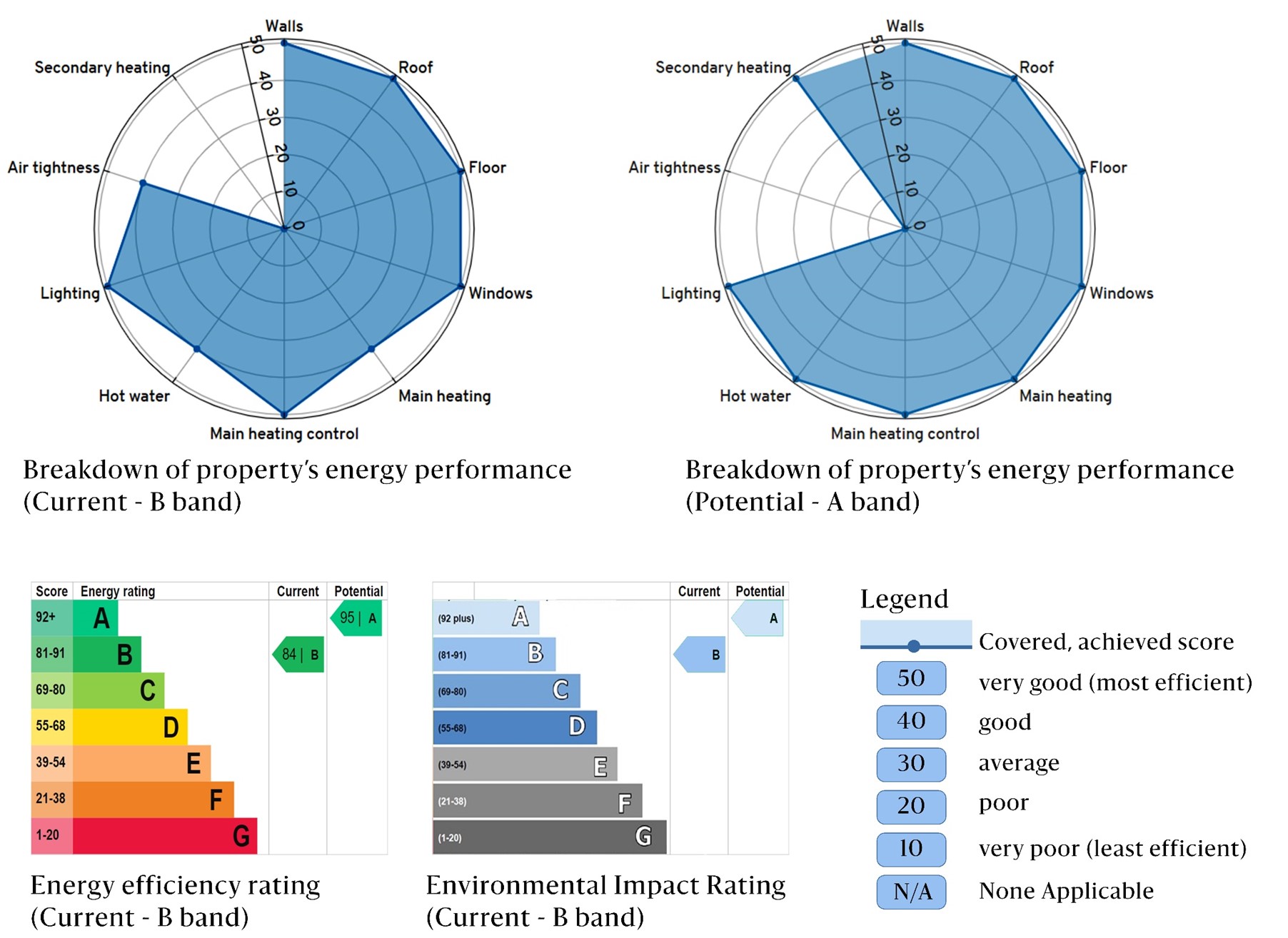

One of the tools to assess building energy efficiency in the UK is the Energy Performance Certificate (EPC), which is defined by the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities as:

A rating scheme that summarises the energy efficiency of buildings; it includes a certificate that gives a property an energy efficiency rating from A (most efficient) to G (least efficient) and is valid for 10 years (DLUHC, 2014).

The EPC is produced using the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP), which is defined by the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy as follows:

The method used to assess and compare the energy and environmental performance of properties in the UK [...] it uses detailed information about the property's construction to calculate energy performance (DBEIS, 2013).

The North Wingfield project has successfully achieved a (B) rating - equivalent to 84 out of a maximum possible 100 points with a high potential for an (A) rating equivalent to 95 points (DLUHC, 2021). This score is the result of

- The use of high-performance materials with very good thermal transmittance properties (walls: 0.20 W/m²K, roof: 0.11 W/m²K, floor: 0.09 W/m²K).

- Well-designed ventilation system that achieves a good air tightness indicator (air permeability 4.9 m³/h.m²).

- Low consumption of primary energy of 94 kWh/m2.

Another indicator is the Environmental Impact Score (EIS), which shows the impact of a building on the environment through the estimated carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions calculated at the time of the EPC assessment (DLUHC, 2014). The higher the score, the lower the building's impact on the environment: like EPC labels, the environmental impact score is graded from A to G (DBEIS, 2014). The project generates 1.4 tonnes of CO2 annually. This is less than a quarter of the 6 tonnes emitted by an average household. By improving the EIS rating to A, CO2 production will be reduced to 0.3 tonnes, which will distinguish the project as one of the most environmentally friendly projects (DLUHC, 2021). Figure 2 shows the EPC and EIS breakdowns of the properties.

Alignment with project research areas

RE-DWELL research framework is based on the interrelationship of three areas: Design, Planning and Construction, Community Participation and Policy. This case relates primarily to design, planning and building and is most evident through:

- Green Building: The analysis of this case has provided insights into the design of green buildings and their development processes, while helping the researcher to understand the principles of industrialised construction. In addition, this case is a 100 per cent social housing development that requires compliance not only with building regulations but also with higher sustainability standards such as the Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM) and Home Quality Mark (HQM).

- Sustainable design: This case helps to understand UK sustainability policy through the applicable codes, standards and guidelines produced by planning and sustainability agencies such as the Building Research Establishment (BRE).

- Inclusive design: The results of this project are considered an example of inclusive design as tenants play an important role in maintaining the sustainability of the community and the environment.

All of the aforementioned made this project a good example for an in-depth study and helped to capture the practice of social housing design and construction in the UK.

* This diagram is for illustrative purposes only based on the author’s interpretation of the above case study

Alignment with SDGs

Although this is a small-scale project, a close examination of the relationship with the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) shows that the project is well aligned with several of the goals:

- Good health and well-being (particularly target 3.4), not only through the architectural characteristics and features but also the social aspects and interaction with surrounding communities, which proved its effectiveness during the last COVID-19 lockdown.

- Affordable and clean energy (targets 7.1 and 7.3). One of the most important features of this project is its high energy efficiency rating, achieved through the integration of innovative construction methods such as high-performance insulation, increased use of natural light and the use of environmentally friendly materials such as locally produced timber frames and bricks.

- Sustainable cities and communities (targets 11.1, 11.6 and 11.7). As part of the larger urban fabric, the project contributes to the overall sustainability agenda of the surrounding districts. Affordability is also one of its distinguishing features, where all of the homes are under the affordability scheme of the local council.

References

Davies, N., & Jokiniemi, E. (2008). Dictionary of architecture and building construction: Routledge.

DBEIS. (2013). Standard Assessment Procedure. December, 2021. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/guidance/standard-assessment-procedure

DBEIS. (2014). Annex B: Energy Performance Certificate data. (URN 14D/192). UK: Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/323946/Annex_B_-_Energy_Performance_Certificate_data.pdf

DK-A. (2021). North Wingfield Project. Retrieved from https://www.dk-architects.com/north-wingfield/

DLUHC. (2014). Energy Performance of Buildings Certificates: glossary. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/989190/Energy_Performance_of_Buildings_Certificates_-_glossary.pdf

DLUHC. (2021). Energy performance certificate (EPC): Breakdown of property’s energy performance. Retrieved from https://find-energy-certificate.service.gov.uk/energy-certificate/8040-7539-6130-7855-8296

HDA. (2021). North Wingfield Road, Description of the design. Retrieved from https://hdawards.org/scheme/16356_scheme-2/

Sterjova, M. (2017). Timber framing – A rediscovered technique for building a home. Retrieved from https://www.wallswithstories.com/uncategorized/timber-framing-a-rediscovered-technique-for-building-a-home.html

Wheatley, P. (2020). New Build Homes, Grassmoor, Chesterfield. Retrieved from https://pacy-wheatley.co.uk/residential-construction-contractors/residential-renovation-chesterfield

Related vocabulary

Building Decarbonisation

Social Housing

Sustainability Built Environment

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 06-11-2023

Read more ->Area: Policy and financing

Created on 17-06-2023

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 24-06-2022

Read more ->Related publications

Alsaeed, M., Hadjri, K., & Nawratek, K. (2024, March). A comparative analysis of UK sustainable housing standards. In 7th Residential Building Design & Construction Conference, Pennsylvania, USA.

Posted on 27-07-2024

Conference

Read more ->Blogposts

A Transdisciplinary Peek Behind Secondment Scenes & Common Challenges to Housing Associations in England

Posted on 22-10-2023

Secondments, Reflections

Read more ->

A Culture of a British Housing Association

Posted on 20-07-2023

Secondments

Read more ->

Sustainable developments in social housing, a secondment at South Yorkshire Housing Association.

Posted on 18-08-2022

Secondments

Read more ->

The case study decoder

Posted on 28-10-2021

Reflections

Read more ->