Area: Design, planning and building

Measuring housing affordability refers to assessing the extent to which households can secure suitable housing in relation to their financial resources and other relevant factors. To date there is no global agreement on measuring housing affordability, nor is there a single metric which comprehensively encompasses all the considerations regarding households' ability to access suitable housing in a convenient location at an affordable cost (Ezennia & Hoskara, 2019; OECD, 2021b).

Several approaches exist to measure housing affordability, with two popular approaches, namely the Income Ratio Method (IRM), and the Residual Income Method (RIM) (Ezennia & Hoskara, 2019; Stone et al., 2011). Both are recommended to be accompanied by housing quality standards to evaluate what a household is paying for and a measure of housing satisfaction (Haffner & Heylen, 2011; OECD, 2021b). However, the perception of what constitutes satisfactory, quality, or affordable housing is subjective. This perception can be influenced by economic and social circumstances that policymakers may not perceive as directly relevant to housing policy (OECD, 2021b).

The Income Ratio Method (IRM) is the most commonly used in policy and housing market-relevant statistics, as it is easy to measure and compare among different countries. It is based on the housing costs to income ratio defined by national authorities not to exceed a certain proportion (Haidar & Bahammam, 2021; Smith, 2007; Stone, 2006). The official EU indicator for IRM is the "Housing Cost Overburden" index. It considers households suffering from affordability issues if more than 40% of their net income is spent on housing costs (AHC, 2019; Hick et al., 2022; OECD, 2020).

However, IRM has been widely criticised as it does not reflect if the household could afford non-housing costs and for how long. The focus on housing costs neglects non-housing costs of utility bills, schools, health, transportation, and so on (AHC, 2019). In this sense, Ezennia & Hoskara, (2019) investigation of the weaknesses of measuring housing affordability emphasised the need to reflect a household's capability to balance current and future costs to attain a house – "access to a house at a certain period" while maintaining other basic expenses without experiencing any financial hardship.

The Residual Income Method (RIM) is the second dominant approach. It recognises that after paying the housing costs, a household might be unable to satisfy its non-housing requirements. Thus, the RIM is the remaining income after subtracting housing costs, based on the idea that Housing Affordability is the households' ability to cover their housing costs while still being able to pay their non-housing expenditures (Stone et al., 2011; Stone, 2006). The residual income method took a step closer to resonating with non-housing costs. However, both Haffner & Heylen (2011) and Bramley (2012) advised that the IRM and RIM approaches "are not interchangeable" and need to be combined to provide a comprehensive perception of housing affordability. This combination becomes apparent when comparing both for different household compositions, health, or work conditions. For instance, a house might be affordable when measured using the IRM from the housing costs standpoint, but it might not be affordable utilising the RIM, which is connected with non-housing costs. This combination is referred to as the Composite Method from which several advanced economic modelling approaches to measure housing affordability were developed (Ezennia & Hoskara, 2019).

However, relying solely on economic criteria to assess affordability and thus overlooking quality and sustainability may not prove sufficient. A poor-quality house can impose hardships on its residents, and an unsustainable dwelling can strain the environment. Mitigating this issue may involve complementing affordability measurements with indicators reflecting housing quality and sustainability to expand the purely economic view (Ezennia & Hoskara, 2019; Haffner & Heylen, 2011; Mulliner et al., 2013; Salama, 2011).

Various indicators can be used to assess housing quality beyond just its cost. These indicators could be seen as serving three primary purposes: (1) to measure the quality of a housing scheme and compare it to others within a country (Homes and Communities Agency, 2011), (2) to measure the quality of housing in one country and compare it to other countries (OECD, 2021b), and (3) to measure housing satisfaction across groups (OECD, 2021a; Riazi & Emami, 2018).

An example of the first purpose is England's Housing Quality Indicators (HQIs) system (Homes and Communities Agency, 2011), which is currently withdrawn. HQIs served as “ measurement and assessment tool to evaluate housing schemes on the basis of quality rather than just cost” design standards mandated for affordable housing providers funded through the National Affordable Housing Programme from 2008 to 2011 and the Affordable Homes Programme from 2011 to 2015. The system comprised ten indicators, which can be categorized into four groups. The first category focused on the location and proximity to amenities and services. The second dealt with site-related aspects such as landscaping, open spaces, and pathways. The third pertained to the housing unit itself, encompassing factors like noise, lighting, accessibility, and sustainability. Lastly, the fourth category addressed the external environment (Homes and Communities Agency, 2011).

To enable meaningful cross-country comparisons, it is crucial that the data used for measuring and assessing these indicators are both available and up-to-date. However, it is important to acknowledge that this may not be the case in all countries, as pointed out by the OECD in 2021 (OECD, 2021b). Consequently, to accurately determine what residents are paying for in terms of quality and to facilitate meaningful comparisons, the OECD 2021 Policy Brief on Affordable Housing has emphasized the necessity of two additional housing quality indicators to complement affordability measurements.

The first proposed indicator is the "Overcrowding Rate," which evaluates whether a dwelling provides sufficient space for household members based on their composition. This metric assesses whether residents have adequate living space according to the size and structure of their household.

The second indicator is the "Housing Deprivation Rates," which gauge inadequate housing conditions. This encompasses issues related to maintenance, such as roofs, walls, floors, foundations, and deteriorating window frames. Moreover, these rates consider the absence of essential amenities, including sanitary facilities. By taking all these factors into account, this indicator offers a comprehensive perspective on the overall quality and habitability of housing in a specific area.

Considering subjective measures of housing affordability can be advantageous when assessing housing affordability and quality based on household perceptions. These measures aim to capture housing satisfaction, reflecting the quality of the dwelling as accommodation (OECD, 2021a). In a broader context, housing satisfaction might be termed residential satisfaction, encompassing not just the dwelling but also its surroundings, including places and people. Residential satisfaction assesses how well the current residence and surrounding environment align with the household's desired living conditions (Riazi & Emami, 2018). Therefore, incorporating subjective measures is valuable in assessing housing affordability, helping to identify the determinants of housing satisfaction. Indicators such as satisfaction with the availability of good and affordable housing are crucial aspects to consider in this context (OECD, 2021a).

When it comes to sustainability indicators, incorporating them into the measurement of housing affordability remains a wicked problem. Finding a single comprehensive measure that encompasses the multifaceted aspects of sustainability related to housing affordability is challenging. The technical complexity stems from the necessity to integrate assessments of household characteristics, environmental impacts, financing, and financial aspects, along with housing stress factors. This challenge is exacerbated by the persistent fluctuations in housing prices and recurring expenses like water and energy bills (AHC, 2019). Hence, easily calculable methods such as the Income-to-Rent Ratio (IRM) and Residual Income Model (RIM) continue to be widely used for assessing housing affordability from a top-down perspective at a macro level. Although imperfect, these methods still provide valuable support for policy decision-making to a certain extent (AHC, 2019; Haffner & Heylen, 2011; OECD, 2021a).

References

AHC. (2019). Defining and Measuring Housing Affordability-An Alternative Approach. In Affordable Housing Commission. www.affordablehousingcommission.org

Bramley, G. (2012). Affordability, poverty and housing need: Triangulating measures and standards. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 27(2), 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-011-9255-4

Ezennia, I. S., & Hoskara, S. O. (2019). Methodological weaknesses in the measurement approaches and concept of housing affordability used in housing research: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE, 14(8), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221246

Haffner, M., & Heylen, K. (2011). User costs and housing expenses. towards a more comprehensive approach to affordability. Housing Studies, 26(4), 593–614.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2011.559754

Haidar, E. A., & Bahammam, A. S. (2021). An optimal model for housing projects according to the relative importance of affordability and sustainability criteria and their implementation impact on initial cost. Sustainable Cities and Society, 64(October 2020), 102535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2020.102535

Hick, R., Pomati, M., & Stephens, M. (2022). Housing and poverty in Europe : Examining the house prices. April.

Homes and Communities Agency. (2011). Housing Quality Indicators. GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/housing-quality-indicators#what-the-indicators-measure

Mulliner, E., Smallbone, K., & Maliene, V. (2013). An assessment of sustainable housing affordability using a multiple criteria decision making method. Omega (United Kingdom), 41(2), 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2012.05.002

OECD. (2020). Social housing: A key part of past and future housing policy. Employment, Labour, and Social Affairs Policy Briefs, OECD, 1–32.

OECD. (2021a). Building for a better tomorrow: Policies to make housing more affordable. Employment, Labour and Social Affairs Policy Briefs, January. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=1060_1060075-0ejk3l4uil&title=ENG_OECD-affordable-housing-policies-brief

OECD. (2021b). Hc.1.5. Overview of Affordable Housing Indicators. 1–5.

Riazi, M., & Emami, A. (2018). Residential satisfaction in affordable housing: A mixed method study. Cities, 82(May), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.04.013

Salama, A. M. (2011). Trans-disciplinary knowledge for affordable housing. Open House International, 36(3), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/ohi-03-2011-b0002

Smith, P. (2007). Life Cycle Costs & Housing Affordability Measurement. Proceedings of the 7th International Cost Engineering Council World Congress & 14th Pacific Association of Quantity Surveyors Congress, 2004, 1–11.

Stone, M. (2006). What is housing affordability? The case for the residual income approach. Housing Policy Debate, 17(1), 151–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2006.9521564

Stone, M., Burke, T., & Ralston, L. (2011). The residual income approach to housing affordability : the theory and the practice. In Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (Issue 139).

Created on 17-10-2023 | Update on 23-10-2024

Related definitions

Affordability

Area: Policy and financing

Created on 27-08-2021 | Update on 20-04-2023

Read more ->Affordability

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 03-06-2022 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Sustainability

Area: Community participation

Created on 08-06-2022 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Life Cycle Costing

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 05-12-2022 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Housing Affordability

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 17-10-2023 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Housing Quality

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 14-10-2024 | Update on 23-10-2024

Read more ->Related cases

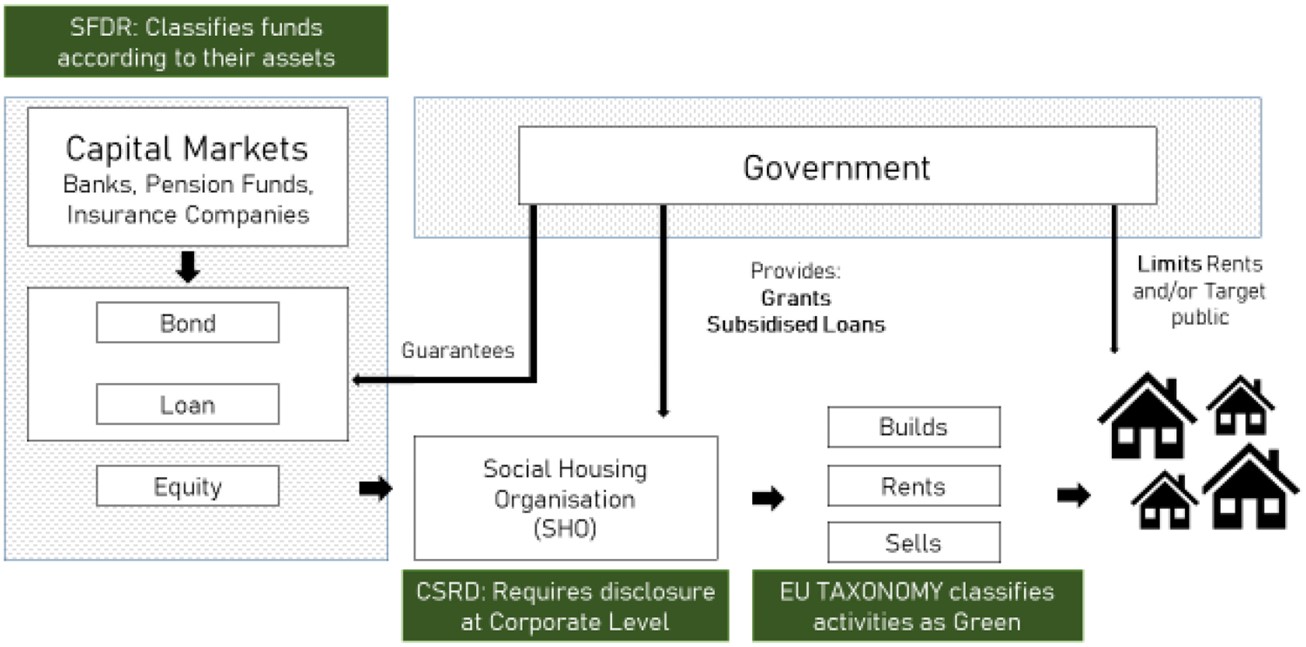

ESG finance and social housing decarbonisation

Created on 05-02-2024

York's Duncombe Square Housing: Towards Affordability, Sustainability, and Healthier Living

Created on 15-11-2024