DARE to Build, Chalmers University of Technology

Created on 04-07-2023

'DARE to build' is a 5–week (1 week of design – 4 weeks of construction) elective summer course offered at the Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden. The course caters for master-level students from 5 different master programmes offered at the Architecture and Civil Engineering Department. Through a practice-based approach and a subsequent exposure to real-world problems, “DARE to build” aims to prove that “real change can be simultaneously made and learned (Brandão et al., 2021b, 2021a). The goal of this course is to address the increasing need for effective multidisciplinary teams in the fields of architecture, engineering and construction (AEC) in order to tackle the ever-growing complexity of real-world problems (Mcglohn et al., 2014), and the pervading lack of a strong pedagogical framework that responds effectively to this challenge. The two main foci of the “DARE to build” pedagogical model are: (1) to train students in interdisciplinary communication, to cultivate empathy and appreciation for the contributions of each discipline, to sharpen collaborative skills (Tran et al., 2012) and (2) to expose students in practice-based, real-world design projects, through a problem-and-project-based learning (PPBL) approach, within a multi-stakeholder learning environment (Wiek et al., 2014). This multi-stakeholder environment is situated in the municipality of Gothenburg and involves different branches and services (Stadsbyggnadskontoret, Park och Naturförvaltningen), local/regional housing companies (Familjebostäder, Bostadsbolaget), professionals/collectives operating within the AEC fields (ON/OFF Berlin, COWI), and local residents and their associations (Hyresgästföreningen, Tidsnätverket i Bergsjön).

Design & Build through CDIO

By showcasing that “building, making and designing are intrinsic to each other” (Stonorov et al., 2018, p. 1), students put the theory acquired into practice and reflect on the implications of their design decisions. Subsequently they reflect on their role as AEC professionals, in relation to local and global sustainability; from assessing feasibility within a set timeframe to the intangible qualities generated or channelled through design decisions in specific contexts. This hands-on learning environment applies the CDIO framework (conceive, design, implement, operate, http://www.cdio.org/), an educational framework developed in the MIT, with a particular focus on the “implementation” part. CDIO has been developed in recent years as a reforming tool for engineering education, and is centred on three main goals: (1) to acquire a thorough knowledge of technical fundamentals, (2) to sharpen leadership and initiative-taking skills, and (3) to become aware of the important role research and technological advances can play in design decisions (Crawley et al., 2014). Therefore, design and construction, combined with CDIO, offer a comprehensive experience that enables future professionals to assume a knowledgeable and confident role within the AEC sector.

Course structure

“DARE to build” projects take place during the autumn semester along with the “Design and Planning for Social Inclusion” (DPSI) studio. Students work closely with the local stakeholders throughout the semester and on completion of the studio, one project is selected to become the “DARE to build” project of the year, based on (1) stakeholder interest and funding capacity, (2) pedagogical opportunities and the (3) feasibility of construction. During the intervening months, the project is further developed, primarily by faculty, with occasional inputs from the original team of DPSI students and support from professionals with expertise relevant to a particular project. The purpose of this further development of the initial project is to establish the guidelines for the 1-week design process carried out within “DARE to build”.

During the building phase, the group of students is usually joined by a team of 10-15 local (whenever possible) summer workers, aged between 16-21 years old, employed by the stakeholders (either by the Municipality of Gothenburg or by a local housing company). The aim of this collaboration is twofold - to have a substantial amount of workforce on site and to create a working environment where students are simultaneously learning and teaching, therefore enhancing their sense of responsibility. “DARE to build” has also collaborated - in pre-pandemic times - with Rice University in Texas, so 10 to 15 of their engineering students joined the course as a summer educational experience abroad.

The timeline for each edition of the “DARE to build” project evolution can be schematically represented through the CDIO methodology, which becomes the backbone of the programme (adapted from the courses’ syllabi):

Conceive: Developed through a participatory process within the design studio “Design and Planning for Social Inclusion”, in the Autumn.

Design: (1) Teaching staff defines design guidelines and materials, (2) student participants detail and redesign some elements of the original project, as well as create schedules, building site logistical plans, budget logs, etc.

Implement: The actual construction of the building is planned and executed. All the necessary building documentation is produced in order to sustain an informed and efficient building process.

Operate: The completed built project is handed over to the stakeholders and local community. All the necessary final documentation for the operability of the project is produced and completed (such as-built drawings, etc.).

In both the design and construction process, students take on different responsibilities on a daily basis, in the form of different roles: project manager, site supervisor, communications officer, and food & fika (=coffee break) gurus. Through detailed documentation, each team reports on everything related to the project’s progress, the needs and potential material deficits on to the next day’s team. Cooking, as well as eating and drinking together, works as an important and an effective team-bonding activity.

Learning Outcomes

The learning outcomes are divided into three different sets to fit with the overall vision of “DARE to Build” (adapted from the course syllabi):

Knowledge and understanding: To identify and explain a project’s life cycle, relate applied architectural design to sustainability and to describe different approaches to sustainable design.

Abilities and skills: To be able to implement co-creation methods, design and assess concrete solutions, to visualise and communicate proposals, to apply previously gained knowledge to real-world projects, critically review architectural/technical solutions, and to work in multidisciplinary teams.

Assessment and attitude: To be able to elaborate different proposals on a scientific and value-based argumentation, to combine knowledge from different disciplines, to consider and review conditions for effective teamwork, to further develop critical thinking on professional roles.

The context of operations: Miljonprogrammet

The context in which “DARE to Build” operates is the so-called “Million Homes Programme” areas (MHP, in Swedish: Miljonprogrammet) of suburban Gothenburg. The MHP was an ambitious state-subsidised response to the rapidly growing need for cheap, high-quality housing in the post-war period. The aim was to provide one million dwellings within a decade (1965-1974), an endeavour anchored on the firm belief that intensified housing production would be relevant and necessary in the future (Baeten et al., 2017; Hall & Vidén, 2005). During the peak years of the Swedish welfare state, as this period is often described, public housing companies, with help from private contractors, built dwellings that targeted any potential home-seeker, regardless of income or class. In order to avoid suburban living and segregation, rental subsidies were granted on the basis of income and number of children, so that, in theory, everyone could have access to modern housing and full of state-of-the-art amenities (Places for People - Gothenburg, 1971).

The long-term perspective of MHP also meant profound alterations in the urban landscape; inner city homes in poor condition were demolished and entire new satellite districts were constructed from scratch triggering “the largest wave of housing displacement in Sweden’s history, albeit firmly grounded in a social-democratic conviction of social betterment for all” (Baeten et al., 2017, p. 637) . However, when this economic growth came to an abrupt halt due to the oil crisis of the 1970s, what used to be an attractive and modern residential area became second-class housing, shunned by the majority of Swedish citizens looking for a house. Instead, they became an affordable option for the growing number of immigrants arriving in Sweden between 1980 and 2000, resulting in a high level of segregation in Swedish cities. (Baeten et al., 2017).

Nowadays, the MHP areas are home to multi-cultural, mostly low income, immigrant and refugee communities. Media narratives of recent decades have systematically racialised, stigmatised and demonised the suburbs and portrayed them as cradles of criminal activity and delinquency, laying the groundwork for an increasingly militarised discourse (Thapar-Björkert et al., 2019). The withdrawal of the welfare state from these areas is manifested through the poor maintenance of the housing stock and the surrounding public places and the diminishing public facilities (healthcare centres, marketplaces, libraries, etc.) to name a few. Public discourse, best reflected in the media, often individualizes the problems of "culturally different" inhabitants, which subsequently "justifies" people's unwillingness to work due to the "highly insecure" environment.

In recent years, the gradual (neo)liberalisation of the Swedish housing regime has provided room for yet another wave of displacement, leaving MHP area residents with little to no housing alternatives. The public housing companies that own MHP stock have started to offer their stock to potential private investors through large scale renovations that, paired with legal reforms, allow private companies to reject rent control. As a result, MHP areas are entering a phase of brutal gentrification (Baeten et al., 2017).

Reflections

Within such a sensitive and highly complex context, both “DARE to Build”, and “Design & Planning for Social Inclusion” aspire to make Chalmers University of Technology an influential local actor and spatial agent within the shifting landscape of the MHP areas, thus highlighting the overall relevance of academic institutions as strong, multi-faceted and direct connections with the “real-world”.

Even though participation and co-creation methodologies are strong in all “Design and Planning for Social Inclusion” projects, “DARE to Build” has still some ground to cover. In the critical months that follow the selection of the project and up to the first week of design phase, a project may change direction completely in order to fit the pedagogical and feasibility criteria. This fragmented participation and involvement, especially of those with less power within the stakeholder hierarchy, risks leading to interventions in which local residents have no sense of ownership or pride, especially in a context where interventions from outsiders, or from the top down, are greeted with increased suspicion and distrust.

Overall “DARE to build” is a relevant case of context-based education which can inform future similar activities aimed at integration education in the community as an instrument to promote sustainable development.

Relevant “DARE to build” projects

Gärdsåsmosse uteklassrum: An outdoor classroom in Bergsjön conceptualised through a post-humanist perspective and constructed on the principles of biomimicry, and with the use of almost exclusively natural materials.

Visit: https://www.chalmers.se/sv/institutioner/ace/nyheter/Sidor/Nu-kan-undervisningen-dra-at-skogen.aspx

https://www.mynewsdesk.com/se/cowi/pressreleases/cowi-hjaelpte-goeteborgs-stad-foervandla-moerk-park-till-en-plats-att-ha-picknick-i-2920358

Parkourius: A parkour playground for children and teens of the Merkuriusgatan neighbourhood in Bergsjön. A wooden construction that employs child-friendly design.

Visit: https://www.sto-stiftung.de/de/content-detail_112001.html https://www.mynewsdesk.com/se/familjebostader-goteborg-se/pressreleases/snart-invigs-bergsjoens-nya-parkourpark-3111682

E.Roussou. ESR9

Read more

->

Marmalade Lane

Created on 08-06-2022

Background

An aspect that is worth highlighting of Marmalade Lane, the biggest cohousing community in the UK and the first of its kind in Cambridge, is the unusual series of events that led to its realisation. In 2005 the South Cambridgeshire District Council approved the plan for a major urban development in its Northwest urban fringe. The Orchard Park was planned in the area previously known as Arbury Park and envisaged a housing-led mix-use master plan of at least 900 homes, a third of them planned as affordable housing. The 2008 financial crisis had a profound impact on the normal development of the project causing the withdrawal of many developers, with only housing associations and bigger developers continuing afterwards. This delay and unexpected scenario let plots like the K1, where Marmalade Lane was erected, without any foreseeable solution. At this point, the city council opened the possibilities to a more innovative approach and decided to support a Cohousing community to collaboratively produce a brief for a collaborative housing scheme to be tendered by developers.

Involvement of users and other stakeholders

The South Cambridgeshire District Council, in collaboration with the K1 Cohousing group, ventured together to develop a design brief for an innovative housing scheme that had sustainability principles at the forefront of the design. Thus, a tender was launched to select an adequate developer to realise the project. In July 2015, the partnership formed between Town and Trivselhus ‘TOWNHUS’ was chosen to be the developer. The design of the scheme was enabled by Mole Architects, a local architecture firm that, as the verb enable indicates, collaborated with the cohousing group in the accomplishment of the brief. The planning application was submitted in December of the same year after several design workshop meetings whereby decisions regarding interior design, energy performance, common spaces and landscape design were shared and discussed.

The procurement and development process was eased by the local authority’s commitment to the realisation of the project. The scheme benefited from seed funding provided by the council and a grant from the Homes and Communities Agency (HCA). The land value was set on full-market price, but its payment was deferred to be paid out of the sales and with the responsibility of the developer of selling the homes to the K1 Cohousing members. Who, in turn, were legally bounded to purchase and received discounts for early buyers.

As relevant as underscoring the synergies that made Marmalade Lane’s success story possible, it is important to realise that there were defining facts that might be very difficult to replicate in order to bring about analogue housing projects. Two major aspects are securing access to land and receiving enough support from local authorities in the procurement process. In this case, both were a direct consequence of a global economic crisis and the need of developing a plot that was left behind amidst a major urban development plan.

Innovative aspects of the housing design

Spatially speaking, the housing complex is organised following the logic of a succession of communal spaces that connect the more public and exposed face of the project to the more private and secluded intended only for residents and guests. This is accomplished by integrating a proposed lane that knits the front and rear façades of some of the homes to the surrounding urban fabric and, therefore, serves as a bridge between the public neighbourhood life and the domestic everyday life. The cars have been purposely removed from the lane and pushed into the background at the perimeter of the plot, favouring the human scale and the idea of the lane as a place for interaction and encounters between residents. A design decision that depicts the community’s alignment with sustainable practices, a manifesto that is seen in other features of the development process and community involvement in local initiatives.

The lane is complemented by numerous and diverse places to sit, gather and meet; some of them designed and others that have been added spontaneously by the inhabitants offering a more customisable arrangement that enriches the variety of interactions that can take place. The front and rear gardens of the terraced houses contiguous to the lane were reduced in surface and remained open without physical barriers. A straightforward design decision that emphasises the preponderance of the common space vis-a-vis the private, blurring the limits between both and creating a fluid threshold where most of the activities unfold.

The Common House is situated adjacent to the lane and congregates the majority of the in-doors social activities in the scheme, within the building, there are available spaces for residents to run community projects and activities. They can cook in a communal kitchen to share both time and food, or organise cinema night in one of the multi-purpose areas. A double-height lounge and children's playroom incite gathering with the use of an application to organise easily social events amongst the inhabitants. Other practical facilities are available such as a bookable guest bedroom and shared laundry. The architecture of its volume stands out due to its cubic-form shape and different lining material that complements its relevance as the place to convene and marks the transition to the courtyard where complementary outdoor activities are performed. Within the courtyard, children can play without any danger and under direct supervision from adults, but at the same time enjoy the liberty and countless possibilities that such a big and open space grants.

Lastly, the housing typologies were designed to recognise multiple ways of life and needs. Consequently, adaptability and flexibility were fundamental targets for the architects who claim that units were able to house 29 different configurations. They are arranged in 42 units comprehending terraced houses and apartments from one to five bedrooms. Residents also had the chance to choose between a range of interior materials and fittings and one of four brick colours for the facade.

Construction and energy performance characteristics

Sustainability was a prime priority to all the stakeholders involved in the project. Being a core value shared by the cohousing members, energy efficiency was emphasised in the brief and influenced the developer’s selection. The Trivselhus Climate Shield® technology was employed to reduce the project’s embodied and operational carbon emissions. The technique incorporates sourced wood and recyclable materials into a timber-framed design using a closed panel construction method that assures insulation and airtightness to the buildings. Alongside the comparative advantages of reducing operational costs, the technique affords open interior spaces which in turn allow multiple configurations of the internal layout, an aspect that was harnessed by the architectural design. Likewise, it optimises the construction time which was further reduced by using industrialised triple-glazed composite aluminium windows for easy on-site assembly. Furthermore, the mechanical ventilation and heat recovery (MVHR) system and the air source heat pumps are used to ensure energy efficiency, air quality and thermal comfort. Overall, with an annual average heat loss expected of 35kWh/m², the complex performs close to the Passivhaus low-energy building standard of 30kWh/m² (Merrick, 2019).

Integration with the wider community

It is worth analysing the extent to which cohousing communities interact with the neighbours that are not part of the estate. The number of reasons that can provoke unwanted segregation between communities might range from deliberate disinterest, differences between the cohousing group’s ethos and that one of the wider population, and the common facilities making redundant the ones provided by local authorities, just to name a few. According to testimonies of some residents contacted during a visit to the estate, it is of great interest for Marmalade Lane’s community to reach out to the rest of the residents of Orchard Park. Several activities have been carried out to foster integration and the use of public and communal venues managed by the local council. Amongst these initiatives highlights the reactivation of neglected green spaces in the vicinity, through gardening and ‘Do it yourself’ DIY activities to provide places to sit and interact. Nonetheless, some residents manifested that the area’s lack of proper infrastructure to meet and gather has impeded the creation of a strong community. For instance, the community centre run by the council is only open when hired for a specific event and not on a drop-in basis. The lack of a pub or café was also identified as a possible justification for the low integration of the rest of the community.

Marmalade Lane residents have been leading a monthly ‘rubbish ramble’ and social events inviting the rest of the Orchard Park community. In the same vein, some positive impact on the wider community has been evidenced by the residents consulted. One of them mentioned the realisation of a pop-up cinema and a barbecue organised by neighbours of the Orchard Park community in an adjacent park. Perhaps after being inspired by the activities held in Marmalade Lane, according to another resident.

L.Ricaurte. ESR15

Read more

->

HOUSEFUL: Els Mestres, Sabadell

Created on 12-03-2025

Innovative Aspects of the Housing Design/Building:

Bloc Els Mestres underwent a major retrofit as part of the EU-funded HOUSEFUL project, integrating innovative circular solutions and services. Tenants were involved through technical systems operation learning and feedback sessions. Tenant engagement methods included interviews and workshops focused on teaching residents how to engage with energy consumption and learning the energy consumption of home systems. As with typical DER, there were four main technical improvements to the building: (1) airtightness, (2) insulation, (3) smart systems, and (4) renewable energies. Circular solutions also incorporated into the retrofit to reduce waste include: (1) reusing the balcony balustrades after raising their height to meet building regulations, (2) recycled wall cladding product, and (3) greywater to be treated using the Nature Based Solution (NBS) of a green wall inside the courtyard.

Construction Characteristics, Materials, and Processes:

After the rehabilitation, the housing block has evolved into a resilient structure with two four-bedroom apartments per floor, spanning the 1st to the 8th floor. Its distinctive design encompasses an array of materials, from natural limestone and cork SATE for insulation to yellow render, terracotta brick, and unobstructed glass panels. With a strategic south-east orientation, the building optimizes natural light, thanks to square windows and cantilevered balconies. Inside, the apartments are designed in a clean, white palette, giving tenants the freedom to infuse their unique style and personal touch.

Energy Performance Characteristics:

Physical deep energy retrofit interventions included: cork external wall insulation; airtightness, fixing holes and fissures, double glazing, and other solutions to reduce thermal coefficient; mechanical ventilation; hydraulic balance valve with differential pressure measurement for the determination of the circulation flow, with insulation; and solar thermal panels, owned by the building owner, together increasing energy efficiency by approximately 50% compared to pre-retrofit. Tenants received technical training on how to use dwelling systems, potentially improving energy efficiency.

Involvement of Users and Other Stakeholders:

The rehabilitation process has involved collaborative decision-making among key stakeholders: LEITAT, non-profit organisation managing and researching sustainable technologies—project co-ordinators; AHC—Housing Agency of Catalonia and building owners; Sabadell Council; WE&B, organised co-creation activities and resident outreach; Housing Europe; members of the tenants’ association; Aiguasol, solar thermal energy; and ITEC, Catalan Institute of Construction and Technology—performed LCAs (life cycle analyses) to decide on cost-effectiveness of circular solutions.

The retrofit project encompassed low levels of tenant consultation and feedback sessions. The importance of managing conflicts that arise during tenant involvement in decision-making processes was recognised. A 'circularity agent' was proposed to teach tenants how to use complex technical systems, potentially fostering in-house expertise.

Relationship to Urban Environment:

Located in Sabadell Sud near the local airport, the block has undergone a significant transformation over the years. It has evolved from an isolated building, the once surrounding fields now transformed into a densely populated urban environment. Notably, it seamlessly integrates into this urban landscape, with a tonally harmonious façade that bathes the surroundings in a warm and visually appealing ambiance. The ground floor is dedicated to the community, fostering a strong connection to the local area and its residents. The nearby pedestrianized streets, adorned with benches, trees, and versatile playground equipment for all age groups, create a welcoming and inclusive atmosphere. This building plays a vital role as it provides accommodation exclusively for social housing residents, contributing to the rich social fabric of the urban community.

S.Furman. ESR2

Read more

->

Deben Fields (Garrison Lane)

Created on 15-11-2023

The review and the analysis of this case is based on several sources of data including project design statements and reports (e.g., planning, architectural, transport, drainage, heritage, landscape, tenure, sustainability and energy), design drawings, planning application and the associated documentation, and archival records obtained from the designers and the East Suffolk planning portal. As well as conducting interviews with the actors involved in the project planning and design, namely the architects, energy system designers and sustainability specialists. Therefore, this review is structured to address various key aspects such as, design, construction, sustainability, community impact and cultural heritage.

1- Design statement

“The initial idea was a cricket pitch on the existing playing field and on the leftover land to develop 25 to 30 housing units. We saw an opportunity to connect the dots by connecting the school site into the cricket field and create better spaces and connectivity for the neighbouring communities […] through prober massing the site was optimised to increase the density to 61 housing units, maximising the views towards the park and generate best returns for the council […] that and investing in East Suffolk Council affordable housing scheme” (M. Jamieson, personal communication, June 13, 2023).

The Deben Fields development is located near the centre of Felixstowe in Suffolk, England (Figure 1). The site was previously occupied by Deben High School, which was built in 1930, surrounded by low-density semi-detached housing. In their design statement, TateHindle, the architects responsible for the project, articulate a design philosophy centred around the creation of an environmentally, socially, and economically sustainable neighbourhood. This vision places paramount importance on people, their lived experiences, and the integration of nature into the living environment (TateHindle, 2021, 2022). The site's redevelopment aligns seamlessly with East Suffolk Council's Housing Strategy, which emphasises the expansion of council-owned affordable housing through innovative and sustainable methods. To adhere to this strategy, the architect chose to preserve and repurpose existing structures on the site, including the school hall and its annexes. These buildings were meticulously retained, redesigned, and refurbished to serve as a new indoor public facility catering for both the current and anticipated population (ESC, 2021).

The project site is 3.89 hectares, of which 2.65 hectares is open green space (cricket pitch and park) and 1.36 hectares is allocated to residential development, with a net density of 53 dwellings per hectare and a total of 93 car parking spaces (61 for residential and 32 for leisure and community services) and 163 cycle spaces (HDA, 2022; TateHindle, 2021). The project is designed according to Passivhaus standards with airtight building envelopes and comprises 61 dwellings with 18 one-bedroom, 28 two-bedroom, seven three-bedroom and eight four-bedroom, spread across semi-detached houses, flats and maisonettes. From a tenure distribution point of view, 68 per cent are available at affordable rents, while the remaining 32 per cent are intended for open market sale (TateHindle, 2021). The average floor area of the housing units is 74.0 m², five per cent above the floor area requirement described by the Nationally Described Space Standard (HDA, 2022).

In terms of ownership, however, the aim is to deliver a ‘tenure neutral’ project, so there is no physical distinction between open-market, shared ownership and affordable rental housing. The tenure mix has been integrated throughout the site to ensure that the project delivers proper housing that meets the needs of the housing market. Figure 2 illustrates Deben Fields tenure distribution and housing typologies plans.

2- Construction

TateHindle's structural design statement outlines their goal of achieving a highly insulated façade construction. This was accomplished through the implementation of load-bearing double stud timber frame walls and load-bearing timber metal web beams at both floor and roof levels. The project uses Typical Passivhaus Foundations (TPFs) to minimise thermal bridging and achieve low U-values for the ground slab construction. Cradden (2019), however, explains that there are multiple challenges when using TPFs, such as soil conditions, material and geological properties (Cradden, 2019). To address these challenges, a shallow foundation method was chosen within the Red Crag Formation, a geological structure in south-eastern Suffolk defined by a basal pebble bed overlaid with coarse shell sand. This approach utilised the mini-pile technique, thereby bypassing the need for extensive and deeper excavations. In addition, Modern Methods of Construction (MMC) are used to maximise the use of off-site construction and achieve high levels of quality through factory-controlled assembly, reduce construction time, minimise noise pollution and construction waste, and reduce CO2 emissions (TateHindle, 2021).

3- Sustainability and energy

“The project has similar challenges to others […] with this project electrification and overheating were the main challenge […] so we did really want to simplify the forms to make it more Passivhaus compliant and cost-effective […] We started from rectangles; obviously you can then add and remove to create interest and increase efficiency” (sustainable design specialist, personal communication, July 20, 2023).

To achieve the planned outcomes of the economically, socially and environmentally sustainable neighbourhood, Deben Fields has set comprehensive objectives including: improving the well-being of residents, promoting pedestrian and child-friendly design, integrating passive design principles such as natural ventilation and daylighting, optimising construction costs and minimising waste through recycling and efficient use of materials, implementing monitoring systems for seamless building management, reducing sequestered carbon by reusing existing structures, promoting affordability as an overarching principle, adopting a fabric-first approach to reduce energy consumption and tackle fuel poverty, addressing future sustainability requirements, using renewable energy through photovoltaics to power communal areas and providing spaces that encourage social interaction such as areas for growing food and for play.

To translate design objectives into a practical design language, the project employed various approaches, as explained in the following subsections.

3.1- Architectural design and technology integration

The primary emphasis is placed on optimising the orientation of the buildings to harness passive solar gain effectively, thereby ensuring ample natural lighting and thermal comfort within indoor spaces (Figure 3). In pursuit of energy efficiency and to reduce overheating impacts, a simplified building form was devised. This involved implementing measures to minimise thermal bridging and establish an airtight building envelope, thereby reducing undesired energy losses. To emphasise the importance of insulation, sufficient provisions were made in the walls to allow for higher levels of thermal protection. A mechanical background ventilation with heat recovery system (MVHR) was used to create a well-ventilated and comfortable living environment. Furthermore, strategically positioned openings, balconies, entrances, sunshades, and shade pergolas contribute to a cohesive architectural language, fostering socially stimulating spaces while adhering to energy-efficient design principles in line with Passivhaus standards. The high-performance triple glazed windows have been carefully positioned and sized to allow natural cross ventilation. All of such techniques maximise control over the building envelope and reduce energy consumption.

3.2- Policy and standards

To achieve the desired sustainability goals, a combination of mandatory and voluntary policies and standards were introduced as part of the project design strategy. Firstly, the mandatory building regulations on sustainability, particularly Part L, which sets specific requirements for insulation, heating systems, ventilation and fuel consumption and aims to reduce carbon emissions by 31 per cent compared to the previous regulations. Secondly, the 'SCLP9.2' – a local planning initiative produced by East Suffolk Council to foment sustainable construction. The SCLP9.2 aims to achieve higher energy efficiency standards resulting in a 20 per cent reduction in CO2 emissions below the target CO2 emission rate, design the dwelling to use less than 110 litres of water per person per day, and encourage the use of locally sourced materials, with a focus on recycling and waste reduction (ESC, 2020, p. 9). Thirdly, the project adhered to Passivhaus standards and set a higher target by meeting higher sustainability standards in terms of energy efficiency, water consumption and material use. CGB Consultants – the sustainability specialist – clarified that with such combination of policies and standards, the dwellings could comfortably exceed the planning target for a 20 per cent improvement over building regulations, as simulated using calculations based on the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP) (CGB, 2021).

4- Community and cultural heritage

In the early design phase, the design team developed a comprehensive communication plan that included public hearings and consultations with the community to inform planners of local needs, foster effective communication with project neighbours and obtain their feedback. However, the restriction of COVID-19 posed a challenge to the effective implementation of the original plan. In response, the architect and the City Council took alternative measures such as formal online consultations, monthly newsletters, social media updates, a website, public exhibitions, public notices, press releases, emails and letters. As a result, the project received critical feedback and concerns around impacts on nature, traffic, existing buildings, privacy, green spaces and alternative renewable energy sources.

Responding to the concerns raised, the project team developed a cycling and pedestrian strategy that introduces the concept of “green corridors", “rain gardens" and “play streets", while carefully allocated parking in line with the National Transport Strategy provides a green roof with photovoltaic panels. The community gardens, use the building structure as a privacy screen and integrate existing culture and heritage into the project (Figure 4).

Although the former Deben High School site is not nationally recognised as a historically significant building, it has become a local landmark with local significance and considerable architectural and historical value. Designed by Cecil George Stillman (1894–1968), a British architect known as a "pioneer of prefabrication" (Hinchcliffe, 2004). The proposed architectural language therefore draws on the existing buildings, particularly the school's building and assembly hall, which is considered the largest historic building on the site. The proposed pedestrian corridors also have helped to make the building more visible and put the assembly hall at the centre of the project (TateHindle, 2021).

5- Final reflections

This section highlights both the successful aspects and the potential areas for improvement arising from the review in the previous sections. This is by addressing the following questions:

What methodologies were deployed within Deben Field that can be classified as exemplifying ‘good' practise?

The proposed designs have looked beyond the initial requirements and original goals and proposed economically, socially and environmentally viable strategies and solutions. Jon Bootland (2011) explains that responsible housing design must adopt a rigorous design standard for low energy consumption, develop high-quality and affordable outcomes, and prioritise user comfort (Bootland, 2011). In response, the project has embraced higher design standards that go beyond mandatory building regulations and systematically addressed the challenges of engaging specialist services (including Passivhaus designers, ecology and biodiversity consultants, sustainable drainage designers and sustainability consultants) with a high level of expertise to provide the necessary technical feedback. In addition, current challenges such as electrification and overheating were proactively addressed by choosing simple architectural forms and integrating renewable energy sources.

While the project initially took a top-down approach, the community was actively involved in the early design phases through a variety of well-organised communication channels (as listed in section 5.4). The project team ensured that responses to planning notices were reviewed, analysed and incorporated into the architectural language of the project. For example, when neighbours raised privacy concerns, the building massing and layout were adjusted to form a privacy screen without compromising the number of dwellings provided. The project has also demonstrated an inclusive design approach that appeals to users of all ages (e.g., community garden and play street). In addition, the design has maximised the benefits of using brownfield sites and seamlessly integrated the existing infrastructure into the project layout, carefully considering the recycling and reuse of materials.

What are the vulnerabilities associated with Deben Fields?

Knox (2015) stated that the high construction costs of ‘green building’ are a common misconception for which there are insufficient studies (Knox, 2015). However, the study by Chegut et al. (2019) shows that “BREEAM – Excellent” certified buildings are 40 to 150 per cent more expensive to build and attributes these higher costs to specialised design costs, material selection, specialised labour and construction time (Chegut, Eichholtz, & Kok, 2019). The Deben Fields project adopted several sustainability features, such as special materials, green roofs and photovoltaic cells. However, it appears that the project has not conducted a thorough life-cycle cost analysis to determine the costs and benefits of these features and whether additional features are needed in the future.

Meanwhile, at the design level and to achieve the intended outcomes, the project complied with several standards and building codes, resulting in a complex and intertwined design structure that makes it difficult to apply the same strategies to other projects. From a sustainable urbanism perspective, density and diverse land use are often considered effective strategies for sustainable development (Carmona, 2021). Despite its central location, the project did not consider density and diversity of land use as a key strategy for its development. For example, the proposed project does not include any retail or commercial uses, and the nearest commercial services are 500 metres from the project (Figure 5).

The Deben Fields project is widely regarded as an example of ‘good practice’ in its field, as reflected in the number of awards it has won. However, in order to accurately assess the results of the project, it is essential to conduct additional post-occupancy studies. These studies will allow for a thorough evaluation of the project's features and provide valuable insights and potential areas for improvement. Another major factor contributing to its prominence is the use of numerous well-designed features. These features have improved the overall performance of the project and highlighted the novel techniques (e.g. play street, environmentally friendly materials, reducing overheating through massing). Therefore, it is crucial to undertake comprehensive documentation of all phases, steps and procedures taken during the design and construction of the project.

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to TateHindle Architects for generously providing the necessary data and information for Deben Fields. Special thanks go to Mike Jamieson for dedicating his time and expertise to discussing the project in detail. Additionally, I extend my appreciation to the anonymous interviewees who provided valuable insights into this case. Thank you all for your support and cooperation.

M.Alsaeed. ESR5

Read more

->

Rural Studio

Created on 16-01-2024

“Theory and practice are not only interwoven with one’s culture but with the responsibility of shaping the environment, of breaking up social complacency, and challenging the power of the status quo.”

– Sambo Mockbee

Overview – The (Hi)Story of Rural Studio

Rural Studio is an off-campus, client-driven, design & build & place-based research studio located in the town of Newbern in Hale County in rural Alabama, and part of the curriculum of the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture of Auburn University. It was first conceptualised by Samuel “Sambo” Mockbee and D.K. Ruth as both an answer to the lack of ethical backbone in architectural education and a critique on the separation of theory and practice illustrated through the curriculum (Freear et al., 2013; Jones & Card, 2011). Both of these reasons mirrored and reinforced the way architecture was practised in the professional world in the early 1990s when, following the dominance of post-modernism, US architects were more preoccupied with matters of aesthetics and style, rather than the social and environmental aspects of their work (Oppenheimer Dean, 2002). Mockbee and Ruth aspired to create a learning environment and shape a pedagogy where students would be introduced to a real-world setting, combining theory with hands-on work and at the same time inscribing incremental, positive change on the Hale County underserved communities.

This incremental change is enabled by three main factors: (1) Auburn University’s commitment to providing stable financial support to the studio, paired with the various sponsorships that the studio receives from individual benefactors, (2) the broad network of collaborations that have been established over the years including local governing officials, external professional experts and consultants, non-profit organisations, schools, and community groups, among others, and (3) the studio’s permanent presence -and the subsequent accountability this presence fosters- in Hale County.

Unlike most design-and-build activities and programmes that adopt a “live” approach (i.e. work with/alongside real stakeholders, in real settings), Rural Studio has continuously implemented various types of projects ranging from housing and parks to community activities (e.g. farming and cooking), with five completed projects per year in Newbern and the broader Hale County area since its launching in 1993 (Freear et al., 2013; Stagg & McGlohn, 2022).

Studio structure and learning objectives

Within the Rural Studio, there are two distinct design-and-build programmes addressing third-year and fifth-year undergraduate students. As currently designed, the third-year programme primarily focuses on sharpening technical skills and exploring the process of transitioning from paper to the building site. In contrast, the fifth-year programme places greater emphasis on the social and organizational aspects of a project. Students may opt to join the Rural Studio activities either once during their third of fifth year, or twice, after spending their first two years on campus and having acquired a solid foundation in the basic skills of an architect.

Third-year programme

The third-year programme accommodates up to 16 students per semester, inviting them to reside and work in Newbern on the construction of a wooden house using platform frame construction. Until 2009, the fall semester focused on design, from conception to technical details, while the spring semester concentrated on construction, culminating in the handover of the completed project to clients or future users. However, several issues called for a profound restructuring, such as the uneven distribution of skills (with students specializing in either design or construction, rarely both), a lack of a continuous knowledge transfer from past to current projects, and students’ limited experience in collaborating with larger teams.

In its current iteration, the third-year programme is dedicated to refining technical skills – such as understanding the structural and natural properties of wood- by implementing an already designed project in phases, while complementing this process with parallel modules on building a knowledge base(Freear et al., 2013; Rural Studio, n.d.).

Seminar in aspects of design – students delve deeper in the history of the built environment of the local context, as well as the international history of wooden buildings.

“Dessein” – in this furniture-making course, students focus heavily on sharpening their wood-working skills by recreating chairs designed by well-known modernist architects.

Fifth-year programme

The fifth-year programme consists of up to 12 students, organized into teams of four, who dedicate a full academic year on a community-focused design-and-build project. These projects, collaboratively chosen by the Rural Studio teaching team and local community representatives, ensure alignment with residents’ needs and programmatic suitability for future users. The programme is student-led, requiring participants to engage in client negotiations, manage financial and material resources, and navigate the local socio-political landscape, among other tasks. Projects can be either set up to be concluded within the nine-month academic year or compartmentalized into several phases, spanning several years. In case of the latter, students are invited to stay a second year, overseeing project progress or completion, if they wish, and become mentors to the next group of fifth-year students.

Curriculum and learning Outcomes

In the Rural studio, “students learn by researching, exploring, observing, questioning, drawing, critiquing, designing, and making” In the Rural studio, “students learn by researching, exploring, observing, questioning, drawing, critiquing, designing, and making” (Freear et al., 2013, p. 34). The annual schedules, or “drumbeats,” as they are called, serve to organise and frame the activities throughout each semester. These activities are designed to enhance the skills and knowledge of students, encompassing technical and practical aspects (such as workshops on building codes, structural engineering, graphic design, and woodworking), theoretical understanding (including lectures and idea exchange sessions with invited experts), and communication skills (involving community presentations and midterm reviews). These activities are conducted in a manner that fosters a team-building approach, with creative elements like the Halloween review conducted in fancy dress, and using food as a unifying element.

In terms of learning outcomes, there are four main categories identified*:

Analysis & Synthesis (researching, exploring, observing, questioning). Students learn how to identify, analyse and navigate the parameters that can influence a design-and-build process and lay out a course of action taking everything they have identified into account.

Design & Construction (drawing, designing, making). Students learn how to navigate a project from conception to construction, and develop a deep understanding of construction technologies, environmental and structural systems, as well as the necessary technical skills to perform relevant tasks.

Teamwork & Management (exploring, questioning, critiquing, designing, making). Students learn how to work in large teams, prioritise and allocate tasks, voice their opinion, negotiate, and manage human and material resources.

Ethos & Responsibility (observing, questioning, critiquing). Through place-based immersion in the local community over the span of 4 to 9 months, students get a deeper understanding of their own role and responsibility as architects within the local sustainable development, especially in contexts of crises, and learn how to trace and assess the socio-political, financial and environmental factors that influence a project’s lifespan.

*author’s own assessment and categorisation, based on relevant readings

Context of operations: Hale County, AL

Hale County, located in Alabama, is a black, working-class area and ranks as the second poorest county in the state (Oppenheimer Dean & Hursley, 2005). Historically, southern states like Alabama and Mississippi have been either the locus of an aestheticisation of the rural life and traditions of the past, especially in popular culture (Cox, 2011), or regarded as socially “backward”, marked by elevated levels of social tension, including discriminatory, racist and white supremacist attitudes (Bateman, 2023). Since the decline in cotton production, which began shortly after the American Civil War, Hale County has faced increasing precarity, with its the local economy heavily reliant on low-wage agricultural industries, like dairy. Given the predominant home-ownership culture in the USA and insufficient welfare safety-nets, the poorest members of communities like Hale County are grappling with urgent housing and living issues, resulting in a sizeable portion of the population facing homelessness or residing in precarious conditions, such as trailer parks (Freear et al., 2013).

Rural Studio provides students from other areas of Alabama and beyond, often hailing from middle-class families, with an opportunity to engage with and be exposed to the harsh realities of a version of the USA they may not have encountered or interacted with before.

Notable initiatives and projects

20k House

Initiated in 2005, the 20K House programme engage students in the creation of affordable housing prototypes tailored to the needs and financial capacity of prospective clients: 20,000 USD is the rough amount a minimum wage worker in the USA can receive as a mortgage. Beyond the immediate provision of housing, the programme aspires to draw academic interest in “well-designed houses for everyone” (Freear et al., 2013, p. 202). Additionally, the initiative incorporates post-occupancy evaluations as integral components of both the pedagogical approach and the continuous improvement of services provided to the local community.

Front Porch Initiative

Launched in 2019, this program revolves around the pressing issue of insufficient housing. Its primary goal is to establish an adaptable, scalable, and robust delivery system for high-quality, well-designed homes designated as real property. The design process takes into account the overall costs of homeownership over time, addressing specifically matters of well-being, efficiency and durability. (Rural Studio, n.d.; Stagg & McGlohn, 2022)

Rural Studio Farm

As part of the Newbern strategic plan, the Rural Studio Farm project seeks to immerse students in the realities of food production, exploring its social, cultural, financial, and environmental implications. Simultaneously, the project addresses the rapid decline in local food production in West Alabama (Freear et al., 2013; Rural Studio, n.d.).

E.Roussou. ESR9

Read more

->

ESG finance and social housing decarbonisation

Created on 05-02-2024

Over the last decades, ESG debt issuance, through green, social or sustainability-linked loans and bonds has become increasingly common. Financial markets have hailed the adoption of ESG indicators as a tool to align capital investments with environmental and social goals, such as the decarbonisation of the social housing stock. According to the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), the green debt market has experienced a 50% growth over the last five years (CBI, 2021). However, the lack of clearly established indicators and objectives has tainted the growth of green finance with a series of high-level scandals and accusations of green-washing, unjustified claims of a company’s green credentials. For example, a fraud investigation by German prosecutors into Deutsche Bank’s asset manager, DWS, has found that ESG factors were not taken into account in a large number of investments despite this being stated in the fund’s prospectus (Reuters, 2022).

To curb greenwashing and improve transparency and accountability in green investments, the EU has embarked on an ambitious legislative agenda. This includes the first classification of environmentally sustainable economic activities: the EU Green Taxonomy (Regulation 2020/852). The Taxonomy is directly linked to the European Commission’s decarbonisation strategy, the Renovation Wave (COM (2020) 662), which relies on a combination of private and public finance to secure the investment needed for the decarbonisation of social housing.

Energy efficiency targets have become increasingly stringent as the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) and its successive recasts (COM(2021)) have been incorporated into national legislation; see for example the French Loi Climate et Resilience (2021-1104, 2021). Consequently, capital expenses for SHOs are set to increase considerably. For example, in the Netherlands, according to a Housing Europe (2020) report, attaining the 2035 energy efficiency targets set by the Dutch government will cost €116bn.

Sustainable finance legislation constitutes an expansion of the financial measures implemented by the EU in recent decades to incentivise energy efficiency standards as well as renovations in the built environment. For more detail on prior EU policies, see Economidou et al. (2020) and Bertoldi et al. (2021). The increased connections between finance and energy performance raise specific questions regarding SHOs’ access to capital markets in light of the shift toward ESG.

The rapidly expanding finance literature on green bonds draws from econometric models to explore the links between investors’ preferences and yields (Fama & French, 2007). This body of literature on asset pricing relies on the introduction of non-pecuniary preferences in investors’ utility functions together with returns and risks to explain fluctuations in the equilibrium price of capital. Drawing from a comparison between green and conventional bonds, Hachenberg and Schiereck (2018) find evidence of the former being priced at a premium. Similarly, Zerbib (2019) also shows a low but significant negative yield premium for green bonds resulting from both investors’ environmental preferences and lower risk levels. The European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (Fatica & Panzica, 2021) documents the dependency of premiums on the issuer with significant estimates for supranational institutions and corporations, but not for financial institutions. While these econometric approaches offer relevant insight into the pricing of green bonds and the incentives for issuers and investors, they do not account for the institutional particularities of social housing, a highly regulated sector usually covered by varying forms of state guarantees and subsidisation (Lawson, 2013).

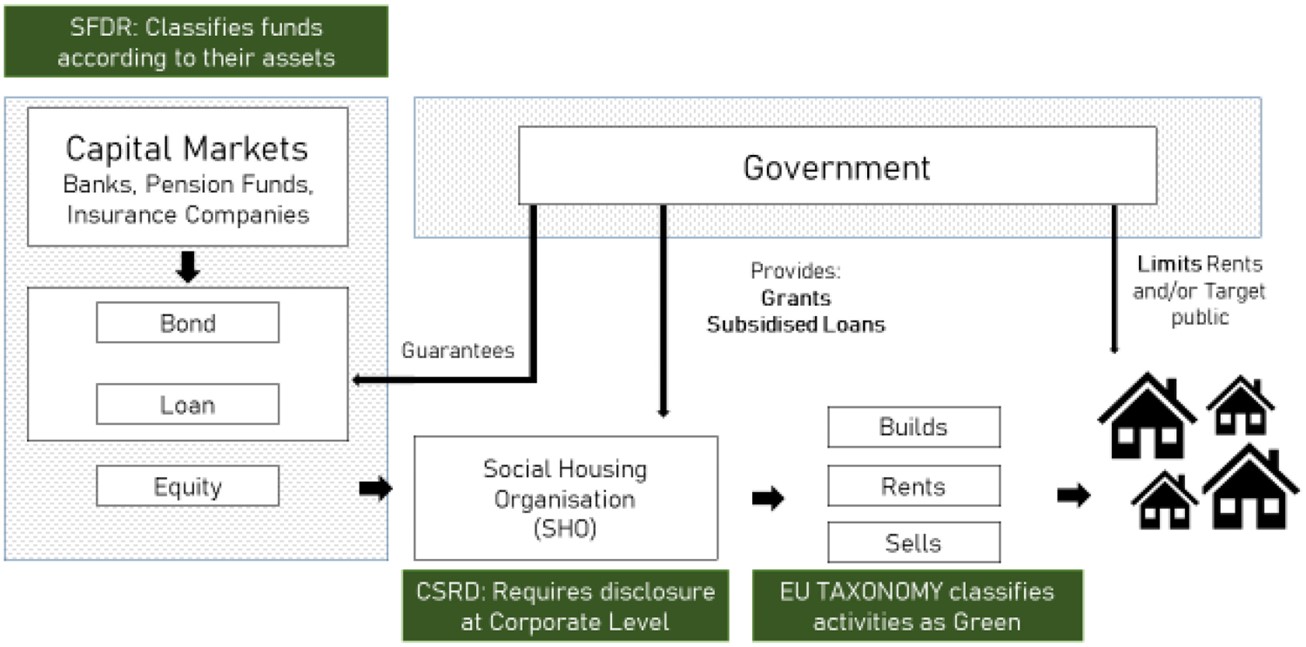

ESG-labelled debt instruments & Related Legislation

Throughout the last two decades, the term ESG finance has evolved to include a large number of financial vehicles of which green bonds have become the most popular (Cortellini & Panetta, 2021). In the social housing sector, ESG comprises a broad array of tools from sustainability-linked loans to less conventional forms of finance such as carbon credits. When it comes to bonds, there is a wide variation in the sustainability credentials among the different types. Broadly speaking, green and social bonds are issued under specific ‘use of proceeds’, which means the funds raised must be used to finance projects producing clear environmental or social benefits. The issuance of these types of bonds requires a sustainable finance framework, which is usually assessed by a third party emitting an opinion on its robustness.

Sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) are an alternative to ‘use of proceeds’. Funds raised in this manner are not earmarked for sustainable projects, but can be used for general purposes. SLBs are linked to the attainment of certain company-wide Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), for example an average Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of “C” in an SHO’s housing stock. These indicators and objectives usually result in a price premium for Sustainable Bonds, or a rebate in interest rates in the case of SLBs or sustainability-linked loans (SLLs) (Cortellini & Panetta, 2021).

While there are international standards for the categorisation of green projects such as the Green Bond Principle or the Climate Bonds Strategy, strict adherence is optional and there are few legally-binding requirements resulting in a large divergence in reporting practices and external auditing. To solve these issues and prevent greenwashing, the EU has been the first regulator to embark on the formulation of a legal framework for green finance through a series of acts targeting the labelling of economic activities, investors, corporations and financial vehicles.

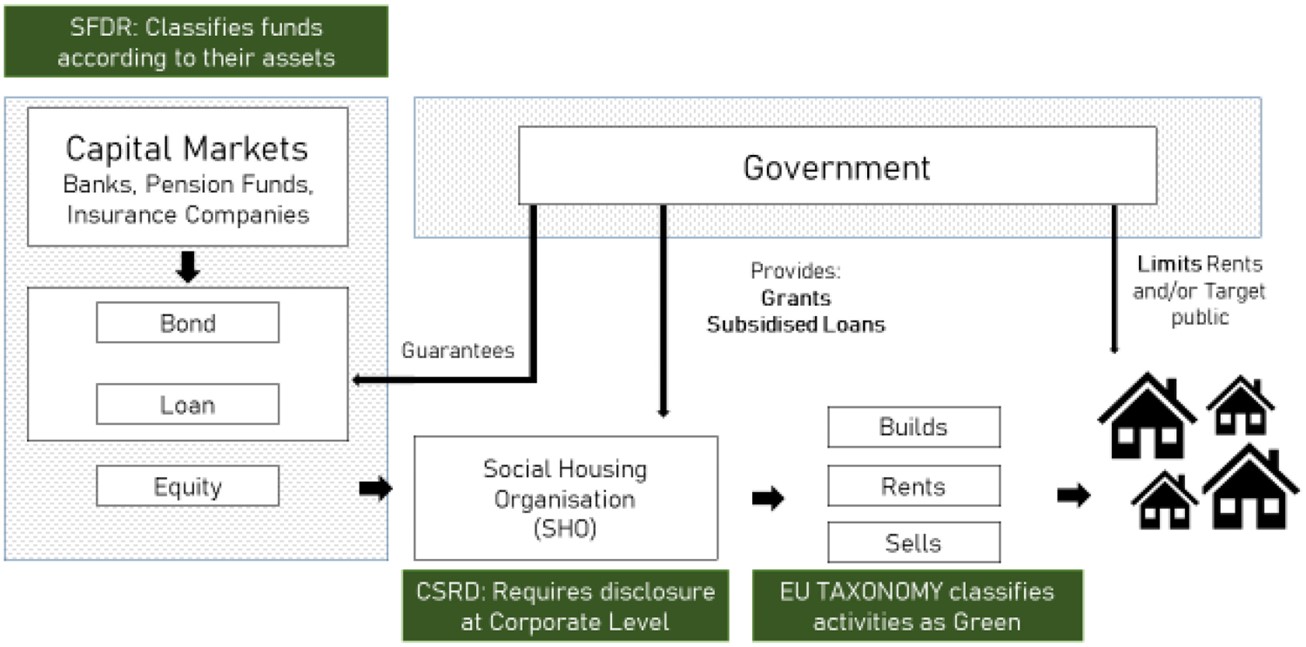

First, the EU Green Taxonomy (Regulation (EU) 2020/852) is the cornerstone of this new legislation since it classifies economic activities attending to their alignment with the objectives set in the European Green Deal (EGD). When it comes to housing, the EU Taxonomy requires specific energy efficiency levels for a project to be deemed ‘taxonomy aligned’. Second, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) (Regulation (EU) 2019/2088) mandates ESG reporting on funds, which tend to consist of exchange-traded collections of real assets, bonds or stocks. Funds are required to self-classify under article 6 with no sustainability scope, ‘light green’ article 8 which incorporates some sustainability elements, and article 9 ‘dark green’ for funds only investing in sustainability objectives. Under the SFDR, which came into effect in January 2023, fund managers are required to report the proportion of energy inefficient real estate assets as calculated by a specific formula taking into account the proportion of ‘nearly zero-energy building’, ‘primary energy demand’ and ‘energy performance certificate’ (Conrads, 2022). Third, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)(COM(2021) 189) increases disclosure requirements for corporations along Taxonomy lines. This legislation, which came into effect in 2023, will be progressively rolled out starting from larger and listed companies and expanding to a majority of companies this decade. Provisions have been made for charities and non-profits to be exempt. However, one of the key consequences of disclosure requirements over funds through the SFDR is its waterfall effect; that is the imposition of indirect reporting requirements as investors pass-on their reporting responsibilities to their borrowers. Fourth, the proposed EU Green Bonds Standards (EU-GBS) COM(2021) 391 aims to gear bond proceedings toward Taxonomy-aligned projects and increase transparency through detailed reporting and external reviewing by auditors certified by the European Security Markets Authorities (ESMA). The main objectives of these legislative changes is to create additionality, that is, steer new finance into green activities (see Figure 1).

While this new legislation is poised to increase accountability and transparency, it also aims to encourage a better management of environmental risks. According to a recent report on banking supervision by the European Central Bank (ECB), real estate is one of the major sources of risk exposure for the financial sector (ECB, 2022). This includes both physical risks, those resulting from flooding or drought and, more relevant in this case, transitional risks, that is those derived from changes in legislation such as the EPBD and transposing national legislation. The ECB points to the need for a better understanding of risk transmission channels from real estate portfolios into the financial sector through enhanced data collection and better assessments of energy efficiency, renovation costs and investing capacity. At its most extreme, non-compliance with EU regulations could result in premature devaluation and stranded assets (ECB, 2022).

In short, the introduction of reporting and oversight mechanisms connects legislation on housing’s built fabric, namely the EPBD, to financial circuits. On the one hand, the EU has been strengthening its requirements vis-à-vis energy efficiency over the last decades. The Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) suggested the introduction of Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) by Member States (Economidou et al., 2020), a rationale followed by France and the Netherlands for certain segments of the housing stock. Currently, policy-makers are debating on whether the EPBD’s recast (COM/2021/802) should incorporate MEPS and make decarbonisation an obligation for SHOs across the EU. On the other hand, legislation on green finance aims to produce incentives and oversight over investments in energy efficient renovation and new build, mobilising the private sector to cater to green projects (Renovation Wave (COM(2020) 662)).

A.Fernandez. ESR12

Read more

->

York's Duncombe Square Housing: Towards Affordability, Sustainability, and Healthier Living

Created on 15-11-2024

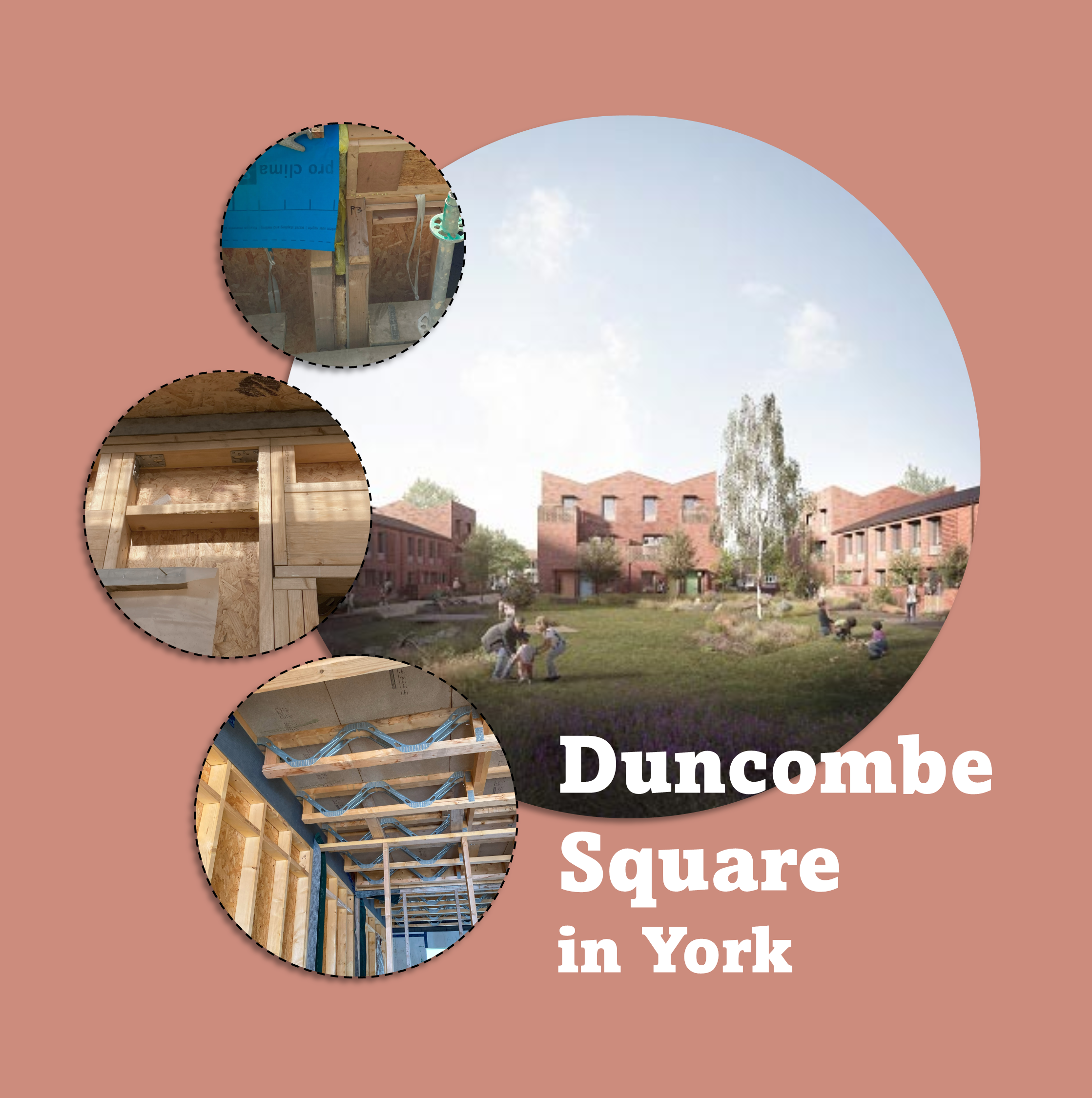

Strengthening Construction Quality and Knowledge Sharing

The City of York's procurement strategy for the Duncombe Square project, as well as other housing sites across the city, focused on two key objectives: ensuring high-quality construction and facilitating knowledge exchange about sustainable building practices. These objectives exemplify the council's commitment to its housing delivery programme.

To achieve housing quality, the council engaged a multidisciplinary design team led by the esteemed architect Mikhail Riches, known for his work on Norwich Goldsmith Street and association with the Passivhaus Trust. This team was supported by RICS-accredited project managers, clerks of work, and valuers to uphold stringent standards.

The project used two complementary approaches to improve the construction and delivery of large-scale Passivhaus projects in the UK. The first approach involved training to advance sustainable construction skills for existing staff, new hires, and students aged 14 to 19, led by the main contractor, Caddick Construction (Passivhaus Trust, 2022). The second approach is sharing knowledge with a broader audience by organising multiple tours during the different construction phases. These tours were designed for developers, architects, researchers, and housing professionals. They showcased Duncombe Square as an open case study, allowing industry peers to learn from and engage directly with project and site managers, reinforcing the project's role as a model for York’s Housing Delivery Programme.

Duncombe Square Housing Design

The design principles of the Duncombe Square project aim to integrate functionality and encourage healthy and sustainable lifestyles. The principles embody the essence of Passivhaus design while ensuring aesthetic appeal. It features low-rise, high-density terraced housing to optimise land use and foster a sense of community. The terraces are strategically positioned close together to maximise solar gain during the winter hours of sunlight, ensuring compliance with the rigorous Passivhaus standards while accommodating a maximum number of residences. The design ensures that each home benefits from natural light and heat while aligning with the Passivhaus energy efficiency and ventilation principles.

The facade design and colour scheme connect with the local architectural identity of traditional Victorian terraces, with a modern twist that cares for indoor environmental quality. It features high ceilings, thick insulated walls, and a fully airtight construction. The design incorporates traditional materials such as brick, enhanced by modern touches of render and timber shingles that blend harmoniously with the local surroundings.

The site plan design reflects a neighbourhood concept that extends beyond the energy-efficient and modern appearance of the houses. Duncombe is designed as a child-friendly neighbourhood, prioritising walking and cycling with dedicated cycle parking for each home. Vehicle parking and circulation are situated along the site's perimeter, ensuring paths are exclusively for pedestrians and play areas. Additionally, shared 'ginnels' provide bike access, enhancing mobility and creating safe play areas for children. This emphasis on pedestrian access enhances community interaction and outdoor activities. The thoughtful landscaping incorporates generous green open spaces at the development's core, complemented by communal growing beds and private planters. These features are intended to be aesthetically pleasing while also encouraging community engagement.

A Construction Adventure

For the main contractor, Caddick Construction, this project represents a distinctive adventure - from procurement to construction to Passivhaus standards - that deviates from traditional British construction practices. Recent UK housing developments often employ "Design and Build" contracts, where the contractor assumes primary responsibility for designing and constructing the project. However, the architects led the design process in this case, necessitating frequent collaborative meetings to discuss detailed execution plans.

During a site visit to the project site in York in September 2023, the contractor’s site manager explained the challenges of constructing and applying Passivhaus standards on a large scale. Unlike traditional construction, Passivhaus demands meticulous attention to detail to ensure robust airtightness of the building envelope. Moreover, building to these standards involves sending progress images to a Passivhaus certifier, who verifies that each construction step meets the rigorous criteria before approving further progress.

The chosen construction method for this project is off-site timber frame construction combined with brick and roughcast render. Prefabricated timber frames mitigate risks for contractors and expedite the construction process. The homes' superstructure employs timber frame technology, ensuring durability and longevity.

A key priority in the construction process is preventing heat loss and moisture infiltration. This involves:

Envelope Insulation: Airtightness is crucial for minimising heat loss. Therefore, the façade installation included airtight boards, tapes, membranes, timber frame insulation, and triple-glazed windows. Indoor airtightness is tested at least four times throughout the construction process to guarantee that residents will live in an airtight house.

Foundation and Floor Insulation: Three layers of insulation between the floor finishing and foundation prevent heat loss, enhance thermal efficiency, and control moisture penetration, protecting against groundwater leakage.

Households’ Health and Wellbeing

Households' health and wellbeing are foundational pillars in the development of the Duncombe Square project. In addition to the robust energy efficiency benefits of Passivhaus standards, this initiative underscores high indoor air quality through Mechanical Ventilation with Heat Recovery (MVHR) units, which improve air quality and help mitigate issues like dampness and mould in airtight houses. To improve outdoor air quality, the design strategically reduces car usage by fostering a pedestrian-friendly environment with expansive green pathways that purify air and encourage outdoor activities. Amenities such as bike sheds with electric charging points and communal "cargo bikes" are also included.

Central to the project is a vibrant communal green space that facilitates relaxation, play, and social interactions—vital for mental and physical health. The scheme enhances residents' wellbeing by ensuring proximity to local amenities, promoting a healthier, more active lifestyle without reliance on vehicles. Extensive pedestrian and cycling paths, alongside wheelchair-friendly features, highlight the project's commitment to inclusivity and a healthy living environment. The design harmoniously integrates with local architecture and includes public amenity spaces that prioritise safe, child-friendly areas and places for social gatherings, fostering a strong community spirit.

When compared with the framework for sustainable housing focusing on health and wellbeing developed by Prochorskaite et al., (2016), the Duncombe project excels in incorporating features such as energy efficiency, thermal comfort, indoor air quality, noise prevention, daylight availability, and moisture control. Moreover, it emphasises accessible, quality public green spaces, attractive external views, and facilities encouraging social interaction and environmentally sustainable behaviours. Its compact neighbourhood design, sustainable transportation solutions, proximity to amenities, consideration of environmentally friendly construction materials, and efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions perfectly encapsulate the framework's objectives for providing sustainable housing focused on health and wellbeing.

Affordability

From a housing provider's perspective, the delivery team faced challenges in achieving a net-zero and Passivhaus standard that is affordable and scalable for large housing developments. For instance, construction costs are subject to pricing risks as contractors raise their prices amid market uncertainties, thereby increasing overall project expenses. Integrating Passivhaus principles is believed to have helped control these costs by simplifying building forms and reducing unnecessary complexities.

Residents' housing affordability is expected to be positively influenced by three key factors: tenure distribution, adherence to Passivhaus standards, and the development's central location. The tenure distribution includes 20% of units for social rent and 40% for shared ownership, offering affordable options for both renters and prospective homeowners. Passivhaus standards further reduce costs by lowering energy consumption through features like PV panels and energy-efficient air-source heat pumps, earning the development an A rating for energy performance and cutting utility bills for residents. Additionally, the central location decreases mobility-related expenses, with easy access to local amenities reducing the need for car use. Together, these factors help promote a sustainable lifestyle and lower overall living costs for residents.

Sustainability: Environmental, Social, and Economic Lens

Environmental sustainability involves two key aspects: (1) reducing resource consumption and (2) minimising emissions during use (Andersen et al., 2020). Duncombe Square's initiatives to reduce resource consumption include:

The dwelling's superstructure utilises low-carbon materials, such as FSC (Forest Steward Council) certified timber framing, which ensures it is sourced from sustainable forestry.

Using recycled newspaper for insulation to minimise environmental impact.

Monitoring the embodied energy of construction materials, including accounting for the energy used in their extraction, production, and transportation.

Sourcing 70% of subcontractors and supplies within 30 miles of the site, as per Passivhaus Trust guidelines, to reduce emissions from long-distance transportation.

To minimise environmental impact during use, the project incorporates:

Air-source heat pumps for heating and solar PV panels on roofs, enabling net-zero carbon energy usage.

Water butts for collecting rainwater for gardening purposes.

Permeable surfaces, rain gardens, and Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDS) to reduce surface runoff in public areas.

Economic sustainability is at the forefront of providing affordable, energy-efficient dwellings that do not impose long-term financial burdens on residents. The project offers affordable dwellings in terms of housing costs, non-housing costs, and housing quality. It also contributes to the broader economy by promoting sustainable building practices and creating future jobs through on-site training programmes. Caddick Construction prioritises the local sourcing of subcontractors and suppliers within 30 miles of the site, thereby reducing transportation costs and supporting the local economy.

Social sustainability is integral to the project, featuring designs that promote community interaction and provide safe, accessible outdoor spaces. The development includes communal green spaces, such as plant-growing areas and a central green space for natural play, enhancing residents' quality of life. Prioritising pedestrian pathways and extensive cycle storage encourages a shift towards sustainable transport options, reducing reliance on cars and promoting healthier, more active lifestyles.

A.Elghandour. ESR4

Read more

->