Retrofit and The Social Agenda

Posted on 08-05-2023

Imagine you are standing at the top of a residential block in a large open park, slightly raised above the ground, with playground equipment catering to various age groups: climbing frames, monkey bars, zip lines, swings… the lot. Walking down the pedestrianised centre of the road, lined with benches and trees (not the norm in arid Barcelona), you arrive at a nine-storey residential building occupying the triangular corner plot. The surrounding buildings occupy a lesser height, so the yellow façade is immediately visible, seamlessly rendered over cork SATE (external wall insulation). Approaching from the street, this is what you would see: at eye level, a west-facing facade with natural limestone wrapping the entire first two storeys; tilt your head upwards, you are looking at yellow-render on the top right two-thirds of the remaining wall, terracotta brick on the top-left third, and the edge of the apartment’s balconies; next, walk around the chamfered the corner, the first two storeys of limestone continues, but, glancing upward again, full balconies are visible on both sides, in the centre of the wall is a central panel of unobstructed glass, and the rest of the wall is terracotta brick; continue your stroll around the building, you are now looking at the south-west facing wall, you see the same material pattern as the west-facing facade, but mirrored. The building is tonally harmonious and the effect is soft and warm—accentuated by the sunshine outside.

The building is called Bloc Els Mestres (The Teachers Block). It was built around 1956 to house the teachers of the adjoining school. The school, the teachers’ residencies, and the expansion of two housing estates were some of the first buildings to occupy the sparsely populated Sabadell Sud location. The site is near Sabadell Airport. By 1984, the expansion had caught up to Bloc Els Mestres and it was no longer isolated between fields but surrounded by residences to the North, West and East. By the year 2000, it was nestled in at all sides. By 2018, however, Bloc Els Mestres sat vacant, neglected, and in major need of renovation.

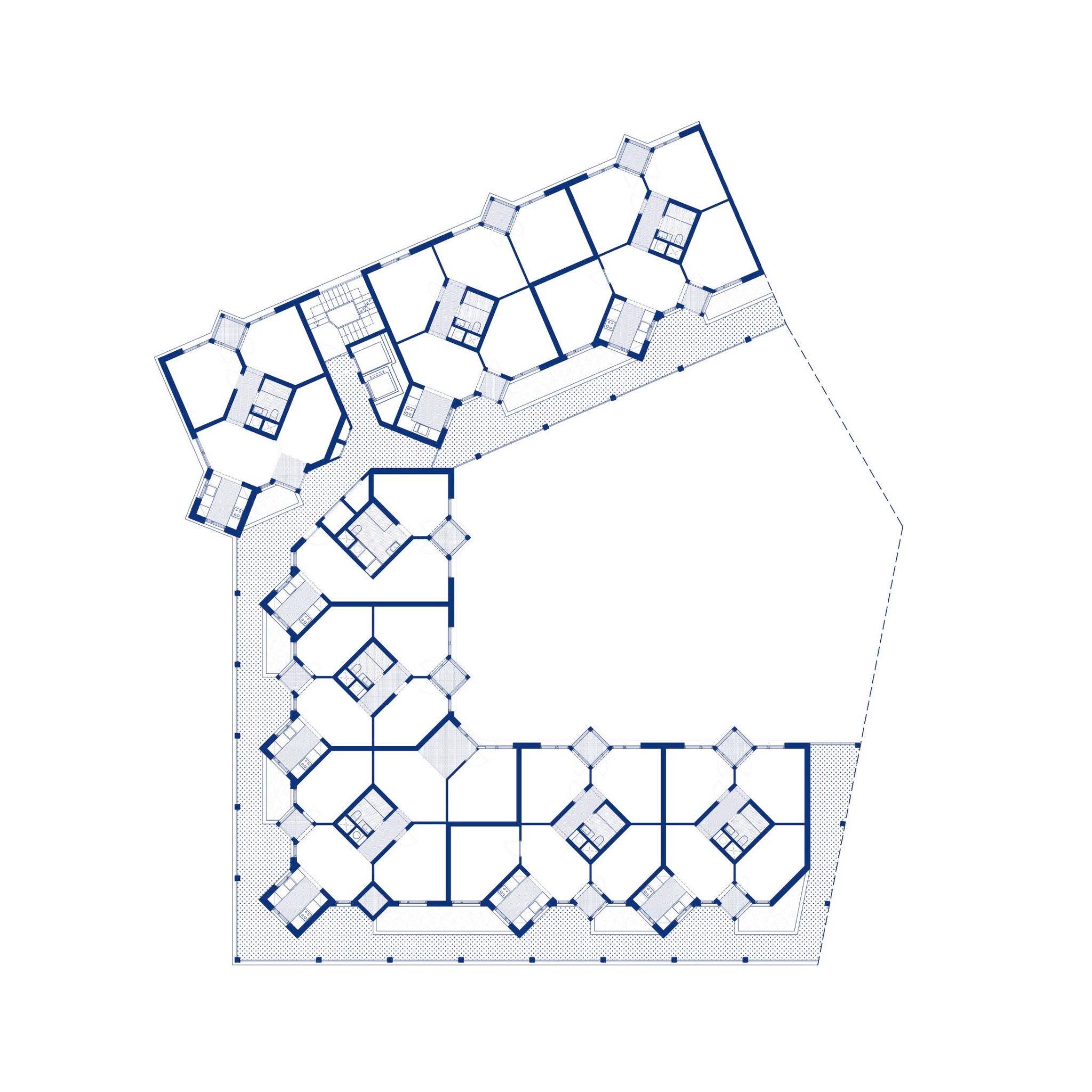

Today, two structurally sound wings fan out either side of the bright central stairwell, with two approximately 100m² four-bedroom apartments per floor —one in each wing (1st – 8th floor). The ground floor belongs to the community. The south-east building orientation allows light to stream through the square windows that punctuate the longest façades; slightly cantilevered balconies also benefit from this orientation. The apartment interiors are a simple white, giving tenants a wide scope to personalise and redecorate.

HOUSEFUL: Innovative circular solutions and services for the housing sector

The Catalan Land Institute—Institut Català del Sòl (Incasól) are the main landowners and developers of social housing in Catalunya. But while they own the land, the buildings themselves are managed by their sister organisation—Agència de l'Habitatge de Catalunya (AHC). Social housing retrofit—or rehabilitación in Castellano—is therefore overseen by the AHC. A lesson I learned quickly after starting my secondment in social housing retrofit… at Incasól. Graciously, introductions were made at the AHC, the owner (unusual) and manager (usual) of Bloc Els Mestres and partner in the HOUSEFUL project.

Bloc Els Mestres has undergone a major retrofit as part of the EU funded HOUSEFUL project (2018-2023) – integrating innovative circular solutions and services into the retrofit of four pilot projects in Spain and Austria. More information can be found here. An ambitious project in sustainable retrofit, physical building upgrades have been combined with smarts systems, reuse, and tenant inclusion through technical systems operation learning and feedback sessions, enhancing social sustainability by ‘consultation’ (Arnstein, 1969) and ‘collaboration’ (Oevermann, 2016). It is now occupied by social housing tenants, who rent the homes directly from the building owner (AHC) at a discounted rate.

I attended two site visits to Els Mestres during my secondment at Incasòl, one included a feedback session with key stakeholders: AHC, Aiguasol, WE&B, Sabadell Council, Saneseco, the Social Association, and Fundació EVEHO – a group who temporarily place young people in HOUSEFUL to aid in their move to Spain.

Bloc Els Mestres feedback session takeaways:

Barrier 1:

How to visualise the benefits of the HOUSEFUL solutions.

Solution1:

Create a report to present the solutions to building owners, manager, and public authority. Place an information board at the building entrance (outside) and inside the building, with a QR code taking people to the website with constantly updated information.

Barrier 2:

Language – not all residents were raised in Spain, and therefore speak and read Spanish or

Catalan.

Solution2:

Consider different dimensions of accessibility. Audio translations, an instruction manual for technical components that is easy to comprehend, beautiful, and visual.

Barrier 3:

The water system needed a lot of space and maintenance; constant analysis of the treated water was also needed - the tenants association asked for removal.

Solution 3:

It was finally agreed with the tenants’ association to install the water system temporarily, in order to evaluate it.

Barrier 4:

A “circularity agent” should be allocated to teach tenants how to use complex technical systems.

Solution 4:

A ‘president’ of the residents could be trained to take this role, in-house expertise and earning a social place in the building.

Barrier 5:

Safeguarding future tenants use of technical systems.

Solution 5:

Contract states the obligation for new tenants to receive technical training regarding how to use the dwelling.

Going forward with my own research, it is important to keep in perspective that conflicts will arise when tenants are involved in decision-making processes. As a result of this, it is important to foresee these potential conflicts, plan possible solutions, and manage expectations.

A huge thanks to Pere Picorelli at Incasòl and Cristina Cardenete, Esther Llorens, and Anna Mestre at AHC for their help, time, access, and guidance.

References:

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A Ladder Of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Planning Association, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

Oevermann, H., Degenkolb, J., Dießler, A., Karge, S., & Peltz, U. (2016). Participation in the reuse of industrial heritage sites: The case of Oberschöneweide, Berlin. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 22(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2015.1083460

Author:

S.Furman

(ESR2)