Diagoon Houses

Created on 25-03-2022 | Updated on 11-11-2022

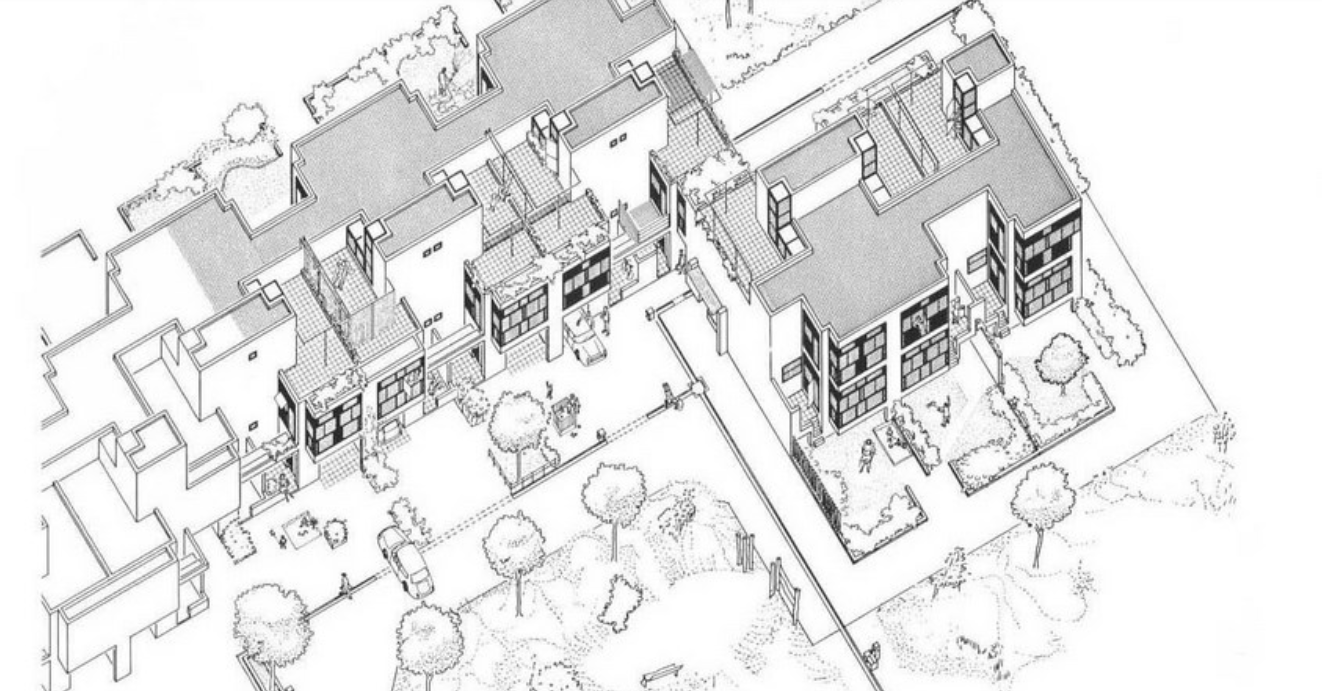

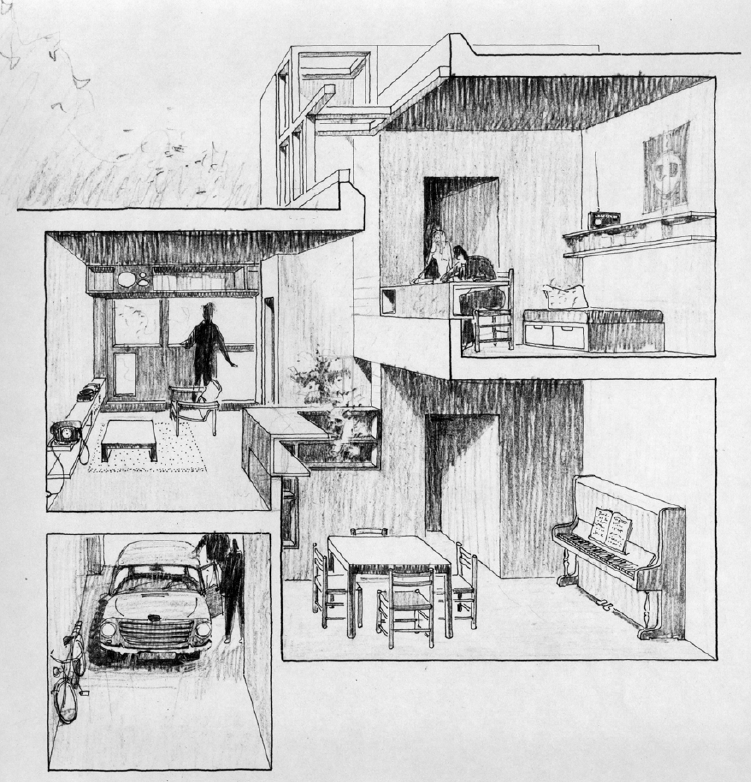

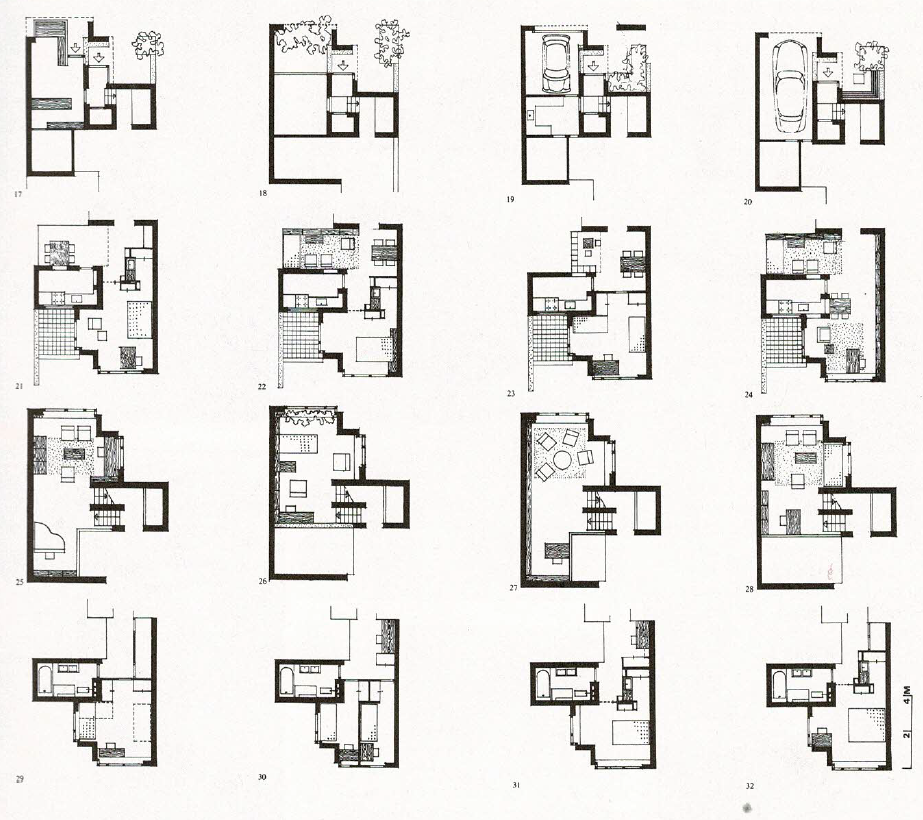

In an increasingly heterogeneous society, with varied family structures, incomes and cultural backgrounds, there is a need to provide for housing alternatives that adapt to the users’ requirements. Since the past century, there has been an increasing concern on how dwellings should incorporate the space-time concept as a way to allow for the change and growth of a dwelling. Herman Hertzberger introduced the term “spatial polyvalency” in the late 1960’s which is strongly related to Habraken’s theories to divide the building into different control levels to facilitate user participation and freedom of choice. This spatial polyvalency was applied in the development of the experimental Diagoon Houses (1967-1971), where the architecture was understood as a carcase that allowed each user to inhabit the space differently, which led to the change and growth of the dwelling, characteristic features of a mass society. This case study proves that true value of participation lies in the effects it has on its participants. The same living spaces when seen from different eyes at different situations, resulted in unique arrangements and acquired different significance. Through the signs of occupancy, the building has become a visual demonstration of its own use.

With regard to its construction system, the repetition of mass-produced components and the prefabrication of the façade elements allowed to lower the cost of the housing units. This intertwining between flexible spatial configurations and the affordability associated with mass production was the spark of mass customisation in the housebuilding industry, which combines the efficiency of prefabrication and the flexibility of personalisation, aiming for a more democratic architecture.

Architect(s)

Herman Hertzberger

Location

Delft, The Netherlands

Project (year)

1967-1971

Construction (year)

1971

Housing type

Terraced houses

Urban context

Suburb

Construction system

Mix of in-situ and prefabricated components

Status

Built

Description

The act of housing

The development of a space-time relationship was a revolution during the Modern Movement. How to incorporate the time variable into architecture became a fundamental matter throughout the twentieth century and became the focus of the Team 10’s research and practice. Following this concern, Herman Hertzberger tried to adapt to the change and growth of architecture by incorporating spatial polyvalency in his projects. During the post-war period, and as response to the fast and homogeneous urbanization developed using mass production technologies, John Habraken published “The three R’s for Housing” (1966) and “Supports: an Alternative to Mass Housing” (1961). He supported the idea that a dwelling should be an act as opposed to a product, and that the architect’s role should be to deliver a system through which the users could accommodate their ways of living. This means allowing personal expression in the way of inhabiting the space within the limits created by the building system. To do this, Habraken proposed differentiating between 2 spheres of control: the support which would represent all the communal decisions about housing, and the infill that would represent the individual decisions. The Diagoon Houses, built between 1967 and 1971, follow this warped and weft idea, where the warp establishes the main order of the fabric in such a way that then contrasts with the weft, giving each other meaning and purpose.

A flexible housing approach

Opposed to the standardization of mass-produced housing based on stereotypical patterns of life which cannot accommodate heterogeneous groups to models in which the form follows the function and the possibility of change is not considered, Hertzberger’s initial argument was that the design of a house should not constrain the form that a user inhabits the space, but it should allow for a set of different possibilities throughout time in an optimal way. He believed that what matters in the form is its intrinsic capability and potential as a vehicle of significance, allowing the user to create its own interpretations of the space. On the same line of thought, during their talk “Signs of Occupancy” (1979) in London, Alison and Peter Smithson highlighted the importance of creating spaces that can accommodate a variety of uses, allowing the user to discover and occupy the places that would best suit their different activities, based on patterns of light, seasons and other environmental conditions. They argued that what should stand out from a dwelling should be the style of its inhabitants, as opposed to the style of the architect. User participation has become one of the biggest achievements of social architecture, it is an approach by which many universal norms can be left aside to introduce the diversity of individuals and the aspirations of a plural society.

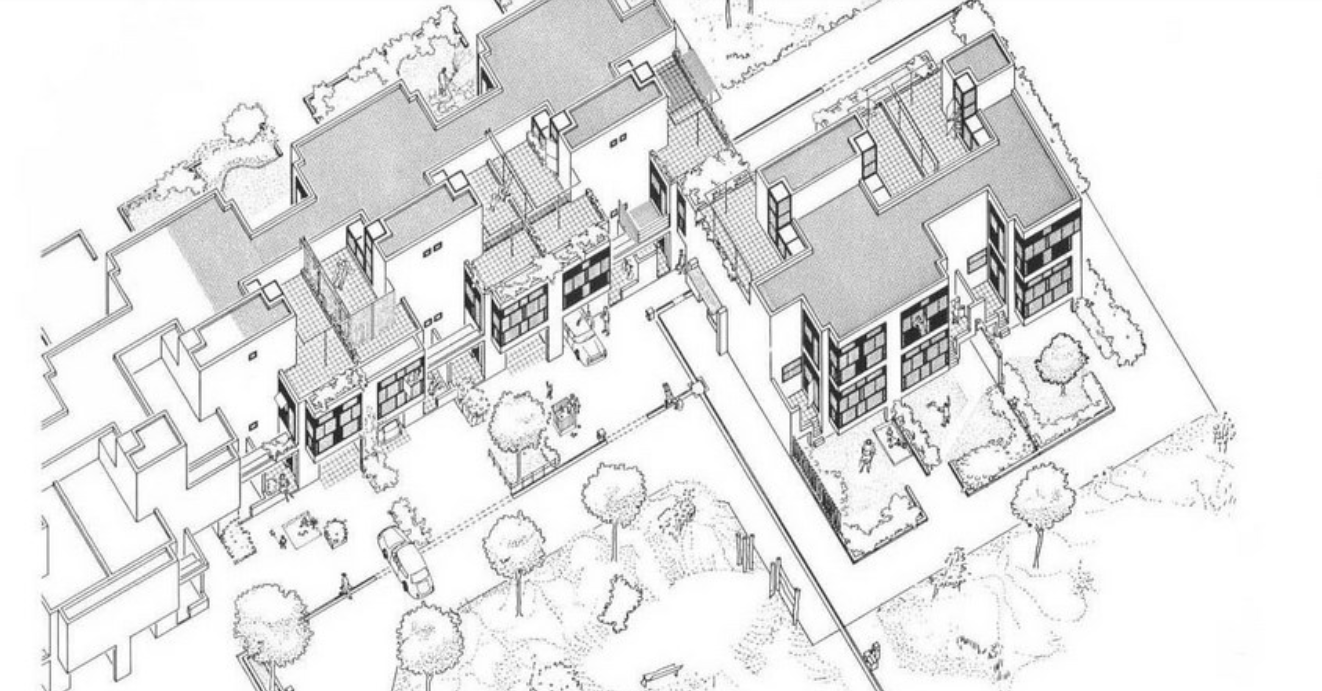

The Diagoon Houses, also known as the experimental carcase houses, were delivered as incomplete dwellings, an unfinished framework in which the users could define the location of the living room, bedroom, study, play, relaxing, dining etc., and adjust or enlarge the house if the composition of the family changed over time. The aim was to replace the widely spread collective labels of living patterns and allow a personal interpretation of communal life instead. This concept of delivering an unfinished product and allowing the user to complete it as a way to approach affordability has been further developed in research and practice as for example in the Incremental Housing of Alejandro Aravena.

Construction characteristics

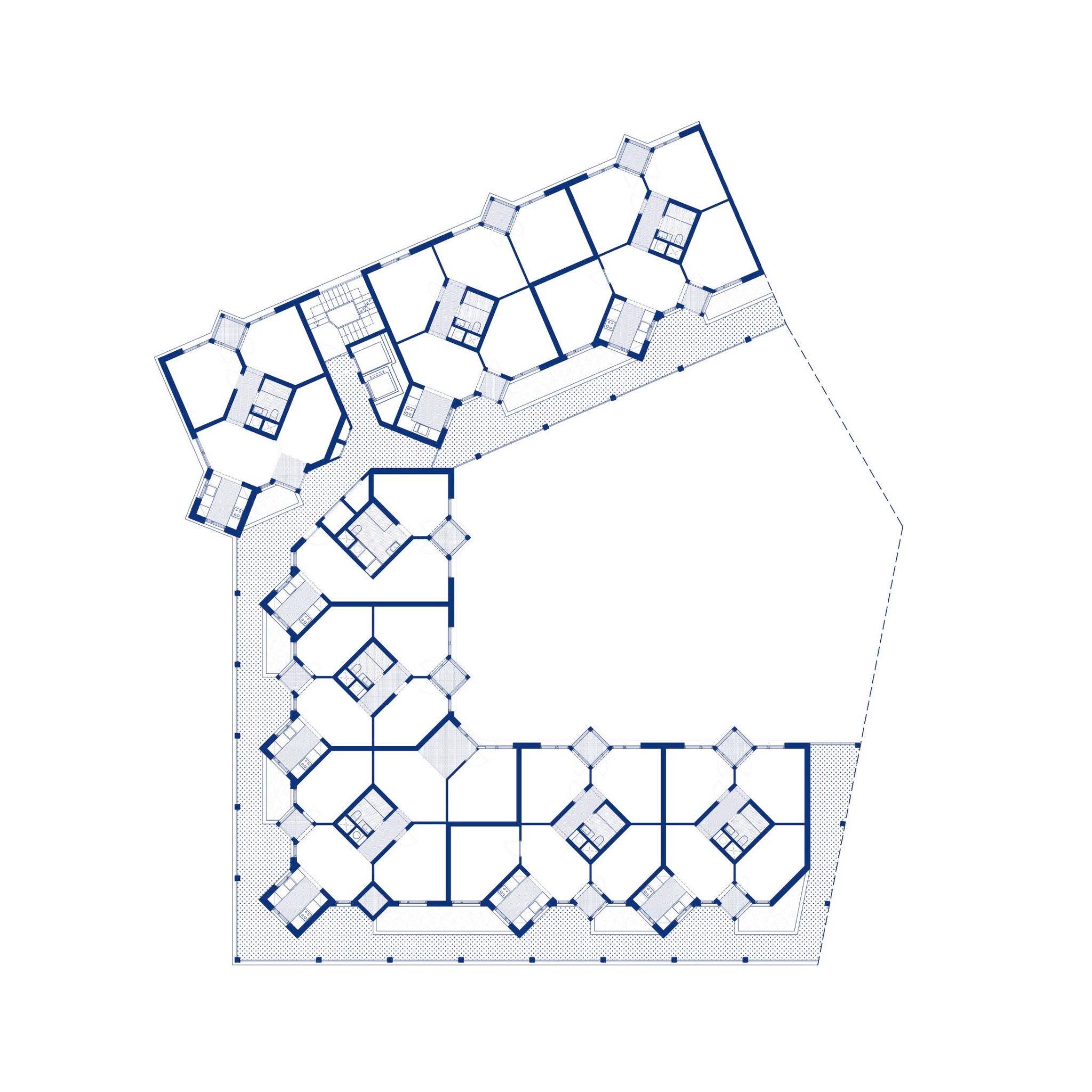

The Diagoon Houses consist of two intertwined volumes with two cores containing the staircase, toilet, kitchen and bathroom. The fact that the floors in each volume are separated only by half a storey creates a spatial articulation between the living units that allows for many optimal solutions. Hertzberger develops the support responding to the collective patterns of life, which are primary necessities to every human being. This enables the living units at each half floor to take on any function, given that the primary needs are covered by the main support. He demonstrates how the internal arrangements can be adapted to the inhabitants’ individual interpretations of the space by providing some potential distributions. Each living unit can incorporate an internal partition, leaving an interior balcony looking into the central living hall that runs the full height of the house, lighting up the space through a rooflight.

The construction system proposed by Herztberger is a combination of in-situ and mass-produced elements, maximising the use of prefabricated concrete blocks for the vertical elements to allow future modifications or additions. The Diagoon facades were designed as a framework that could easily incorporate different prefabricated infill panels that, previously selected to comply with the set regulations, would always result in a consistent façade composition. This allowance for variation at a minimal cost due to the use of prefabricated components and the design of open structures, sets the foundations of the mass customization paradigm.

User participation

While the internal interventions allow the users to covert the house to fit their individual needs, the external elements of the facade and garden could also be adapted, however in this case inhabitants must reach a mutual decision with the rest of the neighbours, reinforcing the dependency of people on one another and creating sense of community. The Diagoon Houses prove that true value of participation lies in the effects it creates in its participants. The same living spaces when seen from different eyes at different situations, resulted in unique arrangements and acquired different significance. User participation creates the emotional involvement of the inhabitant with the environment, the more the inhabitants adapt the space to their needs, the more they will be inclined to lavish care and value the things around them. In this case, the individual identity of each household lied in their unique way of interpreting a specific function, that depended on multiple factors as the place, time or circumstances. While some users felt that the house should be completed and subdivided to separate the living units, others thought that the visual connections between these spaces would reflect better their living patterns and playful arrangement between uses.

After inhabiting the house for several decades, the inhabitants of the Diagoon Houses were interviewed and all of them agreed that the house suggested the exploration of different distributions, experiencing it as “captivating, playful and challenging”1. There was general approval of the characteristic spatial and visual connection between the living units, although some users had placed internal partitions in order to achieve acoustic independence between rooms. One of the families that had been living there for more than 40 years indicated that they had made full use of the adaptability of space; the house had been subject to the changing needs of being a couple with two children, to present when the couple had already retired, and the children had left home. Another of the families that was interviewed had changed the stereotypical room naming based on functions (living room, office, dining room etc.) for floor levels (1-4), this could as well be considered a success from Hertzberger as it’s a way of liberating the space from permanent functions. Finally, there were divergent opinions with regards to the housing finishing, some thought that the house should be fitted-out, while others believed that it looked better if it was not conventionally perfect. This ability to integrate different possibilities has proven that Hertzberger’s experimental houses was a success, enhancing inclusivity and social cohesion. Despite fitting-out the inside of their homes, the exterior appearance has remained unchanged; neighbourly consideration and community identity have been realised in the design. The changes reflecting the individual identity do not disrupt the reading of the collective housing as a whole.

Spatial polivalency in contemporary housing

From a contemporary point of view, in which a housing project must be sustainable from an environmental, social and economic perspective, the strategies used for the Diagoon Houses could address some of the challenges of our time. A recent example of this would be the 85 social housing units in Cornellà by Peris+Toral Arquitectes, which exemplify how by designing polyvalent and non-hierarchical spaces and fixed wet areas, the support system has been able to accommodate different ways of appropriation by the users, embracing social sustainability and allowing future adaptations. As in Diagoon, in this new housing development the use of standardized, reusable, prefabricated elements have contributed to increasing the affordability and sustainability of the dwellings. Additionally, the use of wood as main material in the Cornellà dwellings has proved to have significant benefits for the building’s environmental impact. Nevertheless, while this matrix of equal room sizes, non-existing corridors and a centralised open kitchen has been acknowledged to avoid gender roles, some users have criticised the 13m² room size to be too restrictive for certain furniture distributions.

All in all, both the Diagoon houses and the Cornellà dwellings demonstrate that the meaning of architecture must be subject to how it contributes to improving the changing living conditions of society. Although different in terms of period, construction technologies and housing typology, these two residential buildings show strategies that allow for a reinterpretation of the domestic space, responding to the current needs of society.

Alignment with project research areas

Even though the Diagoon experimental houses were built in the late 1960s with very different building techniques, planning, or financing schemes, some of their features and achievements demonstrate a significant relevance with the three research areas of the RE-DWELL trandisciplinary research.

With regard to Design, Planning and Building, the project promotes resilient design by creating a system that can adapt and incorporate new uses over time supporting the creation of building regeneration through versatility and flexible housing layouts. This, along with the use of prefabricated components to lower the costs making it possible to approach a greater segment of society, leads to a democratization of housing. In addition, Diagoon could be considered as sustainable housing in the way it promotes social cohesion, green spaces and integrates changes with minimum waste.

The case study demonstrates a strong alignment with the Community Participation area, where not only the interior arrangements were completely decided by the users, but as well the boundaries between their individual green spaces were agreed between neighbours, stimulating collective activities and decision-making amongst them. The control levels proposed by Habraken are exemplified in the different ways of participation, from the urban level until the individual dwelling layout.

Regarding Policy and Financing, the approach that Hertzberger proposes by dividing the house into the support and the infill, could potentially facilitate certain financial innovative strategies to increase housing affordability, as for example the shared ownership schemes.

Therefore, in order to implement an affordable and flexible housing system supported by community participation, the three research areas should be taken into account, as the interrelations and dependencies between each other would be necessary for a successful outcome.

* This diagram is for illustrative purposes only based on the author’s interpretation of the above case study

Alignment with SDGs

Although the Sustainable Development Goals had not been established at the time when this project was developed, the examined case study suggests several alignments with some of the goals and targets. There are many qualities that could be extracted from these experimental houses to be incorporated in future housing developments.

With regard to the SDGs 9 and 12, the Diagoon Houses support the construction of sustainable and resilient infrastructures as well as reducing the waste generation. The intrinsic polyvalency in the living spaces enables the user to change the way of inhabiting the dwelling without having to make major changes to it. The project enhances resiliency by providing a carcase that allows the flexibility to host a family with or without children, one who wishes to develop professional activities at home or even the alternative to create an independent studio to rent. Furthermore, this is tightly linked with the way in which this project fosters SDG 10, as it promotes social and economic inclusion. The fact that the property is given unfinished to the user means that each household determines their internal fit-out based on the most suitable for each economy at that given moment, being able to incorporate improvements over time. Consequently, this variability of economic means and needs in a multi-family development could encourage social inclusion.

Finally, the Diagoon Houses are especially related to the SDG 11 as it approaches the goal in multiple ways. This paradigmatic project could serve as an example to develop affordable housing as it demonstrates that low-budget construction is not opposed to high-quality architecture. In addition, it fosters an inclusive and sustainable urbanization by supporting participatory design and allowing diverse family structures to coexist.

References

Literature:

Aravena, A. (2016) Creando Una Nueva Forma de Habitar. E2E. (n.d.). Retrieved September 19, 2022, from https://www.e2echile.com/vivienda-incremental.html

Grijalba Bengoetxea, A., Merino del Río, R., & Grijalba Bengoetxea, J. (2019). Representando el tiempo: polivalencia espacial en las viviendas Diagoon y Centraal Beheer. EGA Revista de Expresión Gráfica Arquitectónica, 24(35). https://doi.org/10.4995/ega.2019.9571

Habraken, N. J., (1966). Three R’s for housing. Amsterdam, Scheltema & Holkema: Forum, vol. XX, nº1

Habraken, N.J. (1961). Supports: An Alternative to Mass Housing (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003014713

Hatch, R. (1984). The Scope of social architecture. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold

Hertzberger, H. (1991). Lessons for students in architecture. Rotterdam: Uitgeverij 010 Publishers

Hertzberger, H. (2016 June). Diagoon Housing Delft 1967-1970. Herman Hertzberger.

https://www.hertzberger.nl/index.php/en/

Hull, a. J., (2010) Architecture in Transition: Herman Hertzberger and The Diagoon Dwellings Revisited.

Retrieved September 19, 2022 from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/567ee040a128e603ba9cfbf0/t/567f50a140667a31535e3787/1451184289847/Architecture+in+Transition.pdf

Smithson, A., Smithson, P. (1979). Signs of Occupancy [Recorded talk] Pidgeon Audio Visuals. https://www.pidgeondigital.com/talks/signs-of-occupancy/

von der Nahmer, R. (2019). Diagoon Woning

https://www.diagoonwoningdelft.nl/visit

Related vocabulary

Affordability

Co-creation

Community Empowerment

Industrialised Construction

Social Sustainability

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 03-06-2022

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 16-02-2022

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 03-06-2022

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 09-11-2023

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 03-06-2022

Read more ->Blogposts

Architecture enables, not dictates ways of life. Good design doesn’t have to come with a hefty price tag

Posted on 02-11-2023

Secondments, Reflections

Read more ->

Towards flexible and industrialised housing solutions

Posted on 24-02-2023

Secondments

Read more ->