Diagoon Houses

Created on 11-11-2022

The act of housing

The development of a space-time relationship was a revolution during the Modern Movement. How to incorporate the time variable into architecture became a fundamental matter throughout the twentieth century and became the focus of the Team 10’s research and practice. Following this concern, Herman Hertzberger tried to adapt to the change and growth of architecture by incorporating spatial polyvalency in his projects. During the post-war period, and as response to the fast and homogeneous urbanization developed using mass production technologies, John Habraken published “The three R’s for Housing” (1966) and “Supports: an Alternative to Mass Housing” (1961). He supported the idea that a dwelling should be an act as opposed to a product, and that the architect’s role should be to deliver a system through which the users could accommodate their ways of living. This means allowing personal expression in the way of inhabiting the space within the limits created by the building system. To do this, Habraken proposed differentiating between 2 spheres of control: the support which would represent all the communal decisions about housing, and the infill that would represent the individual decisions. The Diagoon Houses, built between 1967 and 1971, follow this warped and weft idea, where the warp establishes the main order of the fabric in such a way that then contrasts with the weft, giving each other meaning and purpose.

A flexible housing approach

Opposed to the standardization of mass-produced housing based on stereotypical patterns of life which cannot accommodate heterogeneous groups to models in which the form follows the function and the possibility of change is not considered, Hertzberger’s initial argument was that the design of a house should not constrain the form that a user inhabits the space, but it should allow for a set of different possibilities throughout time in an optimal way. He believed that what matters in the form is its intrinsic capability and potential as a vehicle of significance, allowing the user to create its own interpretations of the space. On the same line of thought, during their talk “Signs of Occupancy” (1979) in London, Alison and Peter Smithson highlighted the importance of creating spaces that can accommodate a variety of uses, allowing the user to discover and occupy the places that would best suit their different activities, based on patterns of light, seasons and other environmental conditions. They argued that what should stand out from a dwelling should be the style of its inhabitants, as opposed to the style of the architect. User participation has become one of the biggest achievements of social architecture, it is an approach by which many universal norms can be left aside to introduce the diversity of individuals and the aspirations of a plural society.

The Diagoon Houses, also known as the experimental carcase houses, were delivered as incomplete dwellings, an unfinished framework in which the users could define the location of the living room, bedroom, study, play, relaxing, dining etc., and adjust or enlarge the house if the composition of the family changed over time. The aim was to replace the widely spread collective labels of living patterns and allow a personal interpretation of communal life instead. This concept of delivering an unfinished product and allowing the user to complete it as a way to approach affordability has been further developed in research and practice as for example in the Incremental Housing of Alejandro Aravena.

Construction characteristics

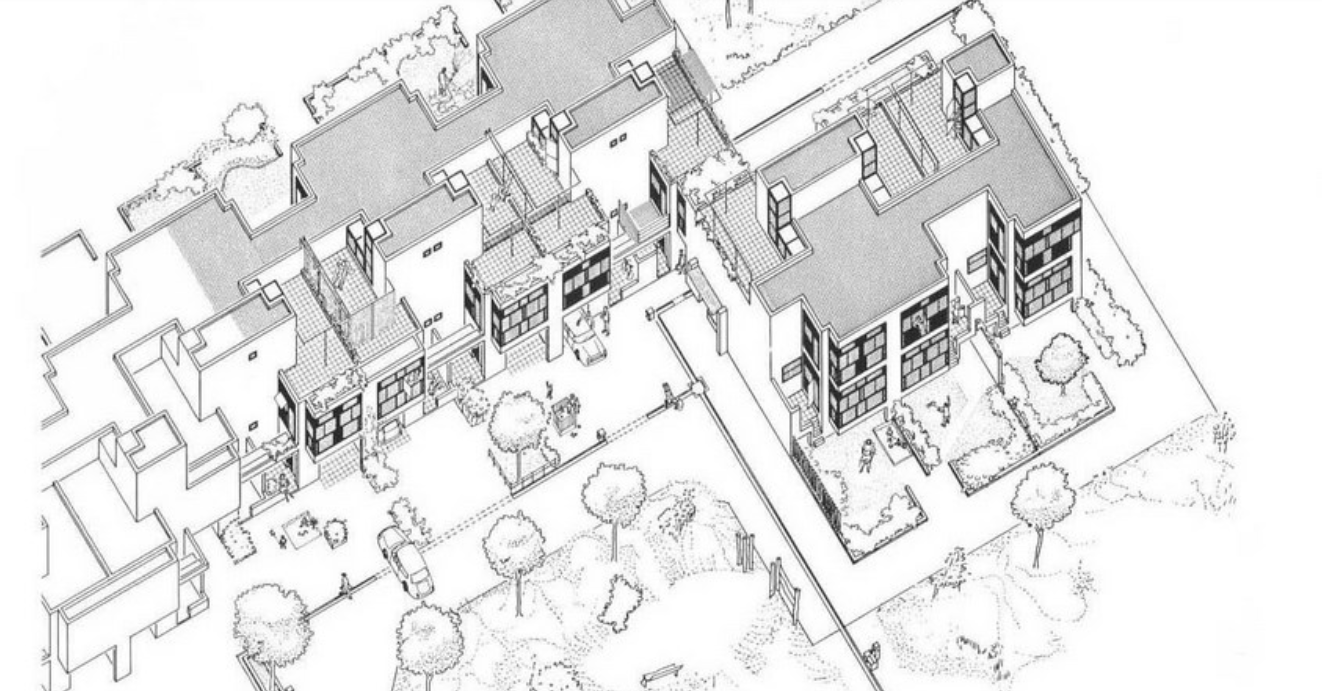

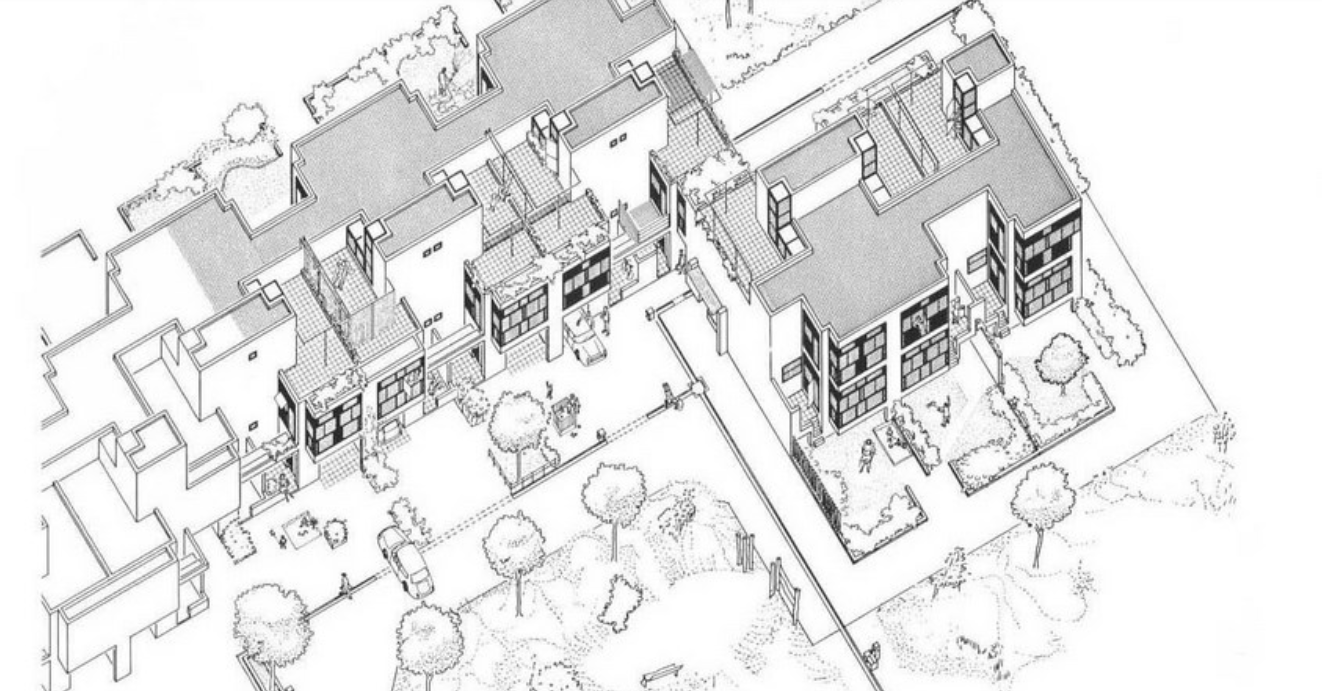

The Diagoon Houses consist of two intertwined volumes with two cores containing the staircase, toilet, kitchen and bathroom. The fact that the floors in each volume are separated only by half a storey creates a spatial articulation between the living units that allows for many optimal solutions. Hertzberger develops the support responding to the collective patterns of life, which are primary necessities to every human being. This enables the living units at each half floor to take on any function, given that the primary needs are covered by the main support. He demonstrates how the internal arrangements can be adapted to the inhabitants’ individual interpretations of the space by providing some potential distributions. Each living unit can incorporate an internal partition, leaving an interior balcony looking into the central living hall that runs the full height of the house, lighting up the space through a rooflight.

The construction system proposed by Herztberger is a combination of in-situ and mass-produced elements, maximising the use of prefabricated concrete blocks for the vertical elements to allow future modifications or additions. The Diagoon facades were designed as a framework that could easily incorporate different prefabricated infill panels that, previously selected to comply with the set regulations, would always result in a consistent façade composition. This allowance for variation at a minimal cost due to the use of prefabricated components and the design of open structures, sets the foundations of the mass customization paradigm.

User participation

While the internal interventions allow the users to covert the house to fit their individual needs, the external elements of the facade and garden could also be adapted, however in this case inhabitants must reach a mutual decision with the rest of the neighbours, reinforcing the dependency of people on one another and creating sense of community. The Diagoon Houses prove that true value of participation lies in the effects it creates in its participants. The same living spaces when seen from different eyes at different situations, resulted in unique arrangements and acquired different significance. User participation creates the emotional involvement of the inhabitant with the environment, the more the inhabitants adapt the space to their needs, the more they will be inclined to lavish care and value the things around them. In this case, the individual identity of each household lied in their unique way of interpreting a specific function, that depended on multiple factors as the place, time or circumstances. While some users felt that the house should be completed and subdivided to separate the living units, others thought that the visual connections between these spaces would reflect better their living patterns and playful arrangement between uses.

After inhabiting the house for several decades, the inhabitants of the Diagoon Houses were interviewed and all of them agreed that the house suggested the exploration of different distributions, experiencing it as “captivating, playful and challenging”1. There was general approval of the characteristic spatial and visual connection between the living units, although some users had placed internal partitions in order to achieve acoustic independence between rooms. One of the families that had been living there for more than 40 years indicated that they had made full use of the adaptability of space; the house had been subject to the changing needs of being a couple with two children, to present when the couple had already retired, and the children had left home. Another of the families that was interviewed had changed the stereotypical room naming based on functions (living room, office, dining room etc.) for floor levels (1-4), this could as well be considered a success from Hertzberger as it’s a way of liberating the space from permanent functions. Finally, there were divergent opinions with regards to the housing finishing, some thought that the house should be fitted-out, while others believed that it looked better if it was not conventionally perfect. This ability to integrate different possibilities has proven that Hertzberger’s experimental houses was a success, enhancing inclusivity and social cohesion. Despite fitting-out the inside of their homes, the exterior appearance has remained unchanged; neighbourly consideration and community identity have been realised in the design. The changes reflecting the individual identity do not disrupt the reading of the collective housing as a whole.

Spatial polivalency in contemporary housing

From a contemporary point of view, in which a housing project must be sustainable from an environmental, social and economic perspective, the strategies used for the Diagoon Houses could address some of the challenges of our time. A recent example of this would be the 85 social housing units in Cornellà by Peris+Toral Arquitectes, which exemplify how by designing polyvalent and non-hierarchical spaces and fixed wet areas, the support system has been able to accommodate different ways of appropriation by the users, embracing social sustainability and allowing future adaptations. As in Diagoon, in this new housing development the use of standardized, reusable, prefabricated elements have contributed to increasing the affordability and sustainability of the dwellings. Additionally, the use of wood as main material in the Cornellà dwellings has proved to have significant benefits for the building’s environmental impact. Nevertheless, while this matrix of equal room sizes, non-existing corridors and a centralised open kitchen has been acknowledged to avoid gender roles, some users have criticised the 13m² room size to be too restrictive for certain furniture distributions.

All in all, both the Diagoon houses and the Cornellà dwellings demonstrate that the meaning of architecture must be subject to how it contributes to improving the changing living conditions of society. Although different in terms of period, construction technologies and housing typology, these two residential buildings show strategies that allow for a reinterpretation of the domestic space, responding to the current needs of society.

C.Martín. ESR14

Read more

->

LiLa4Green

Created on 04-07-2023

Background

Over the last decades, international and national environmental policies have been designed and implemented to counteract the impact of the emerging climate change, this forcing many cities around the globe to adapt their urban environment and update their planning strategies. On a local level, targeted solutions to improve urban microclimates play a catalytic role on the sense of urban comfort, especially in densely built areas lacking green. Such nature-based and cost-effective solutions which provide environmental, social and economic benefits for resilience (European Commision Research and Innovation, n.d.), as well as comprehensive green and blue infrastructure strategies that promote the use of natural processes and vegetation to achieve landscape and water management benefits in an urban context (Victoria State Goverment Department of Environment Land Water and Planning, 2017) can counteract the effects of rising temperatures and provide resilience for cities and inhabitants (Roehr & Laurenz, 2008). However, their implementation and maintenance face many challenges, such as administrative limitations and lack of awareness or acceptance by the local stakeholders and residents (Hagen et al., 2021; Tötzer et al., 2019).

Working to address this challenge in a holistic manner, the LiLa4Green project, as part of the Smart Cities Initiative, aims to foster the implementation of nature-based solutions in the city of Vienna, by integrating a LL approach that focuses on social innovation and knowledge-sharing. The main goals of the project include the collaborative identification of challenges and potentials, the implementation of co-created solutions in the streetscape and the visualisation of the effects of potential solutions in a creative way to raise awareness and activate participants (Hagen et al., 2021).

The project is funded by the Climate and Energy Fund and is carried out by an interdisciplinary consortium consisting of research, academic and community partners. The project’s methodology has been tested in two residential neighbourhoods, ‘Quellenstraße Ost’ in the 10th district and ‘Kreta’ in the 14th district of Vienna. Both neighbourhoods are characterised by dense urban structures and insufficient public and green spaces, and their population consists predominantly of young, low-income immigrant groups who are poorly qualified and which suffer a high unemployment rate (Hagen et al., 2019).

Methodological Approach

The project was implemented along two parallel lines of work. The first refers to a scientific approach conducted by the research consortium. This initiated with the open space and microclimatic analysis of the areas, the results of which were seen in context with the climate of the whole city, concluding to the areas’ characterisation. A demarcation as ‘vulnerable with respect to densification’ (Tötzer et al., 2019, p. 3) reflects the high density and bioclimatic stress of the neighbourhood. The analysis offered valuable insights in identifying priority spots, i.e., small-scale heat islands, and was followed by discussions on greening potentials and recommendations about the areas’ needs and characteristics.

In parallel, a participatory process was initiated in the focus areas to inform the scientific findings on the most problematic locations in the neighbourhood based on the local knowledge and experience of residents and local stakeholders. At the same time, through the establishment of the LL as an alternative to top-down city planning strategies, residents moved from being information facilitators to co-creators.

Following this approach of empowering residents to actively participate in the development of solutions that affect their living environment, the LL investigated ways to raise public awareness on mitigation and measures to facilitate citizens’ adaptation to climate change and to ensure a broad acceptance for the green-blue infrastructure among the general public, through the design and testing of multiple and diverse smart user participation and visualisation methods. A combination of innovative social science methods with the latest digital technology was put forward to facilitate the dissemination of information of the diverse functionalities of green and free spaces, testing also new methods of visualisation of the effects, such as Augmented and Virtual Reality, for more informed decisions (www.lila4green.at). Focusing further on the visibility and traceability (Hagen et al., 2021, p. 393) of the added value of the potential interventions, the monitoring phase included a combination of measurements, simulations and surveys, while in the assessment phase, innovative tools such as crowdsourcing and maps were employed to correlate multiple measurements such as costs and maintenance requirements.

Activities

The innovative methodology was tested in practice in a range of different activities organised by the LL that opened the research to citizens and stakeholders in an interactive format. The participatory process initiated with the LiLa4Green research team coming together to design the operation and context of the LL. The activities in the LL began with the ‘Start Workshop’, a knowledge-gathering meeting in which research team members and relevant stakeholders (representatives of municipal agencies and local institutions) came together to discuss constrains, potentials in the project area and the mutual benefits.

This introductory event was followed by the four cornerstones of the project, namely the ‘Green Workshops’ (GWs) that took place every 6 months and involved the research team, stakeholders and citizens. In preparation of each of these four events, a set of activities was organised on site, related to the objectives of the foregoing events, as well as the results of the previous ones. For instance, before the first Green Workshop that focused on ‘sharing information, building mutual understanding and establishing social connections’ (Tötzer et al., 2019, p. 5), the research team conducted on site activation activities which included the creation of a temporary space for conversations using pictures, signs and questions to approach the people passing by, and also engaging them through game-like activities of mapping and voting.

The first workshop started and concluded with a survey. The comparison of the answers of both surveys enabled the organisers to detect changes in the perception of participants on the topic and hence the success of the workshop in the transfer of knowledge. The workshop was organised in two parts that differentiated on the flow of knowledge from the research group to the participants and reversely, using posters, a memory set and a flyer as tools for communication.

Working on the feedback from the first workshop, the second event focused on the realisation of the first urban intervention, a parklet, that was developed as a student project at intended design studios at the TU Wien and then selected by the participants of the LL. Furthermore, using a smart interaction tool with AR technology on site, participants were given the chance to visualise and provide their feedback on potential greening interventions.

Having built trust between the participants and the research team, the third workshop aimed at the identification of the potential uses of the open space through gamification. The participants designed adaptation activities to respond to the scientifically identified conditions and further grounded their decisions to real restrictions, such as budget. In the same workshop, participants tested the AR tool that was further developed by the research team according to the feedback from the second workshop.

Finally, the fourth workshop dealt with the collective implementation of the developed proposals. Due to the pandemic outbreak the workshop was delivered in a digital format and the results were eventually implemented in the summer 2020.

Communication and Sharing Experience

Parallel to the workshops and activities, the consortium gave a great value to the communication and dissemination of LiLa4Green within and outside the focus areas by sending out a frequent newsletter and an Explain Video to attract and maintain participants’ motivation. Surveys and questionnaires were used to incorporate the feedback for the next stages, and experiences were shared via a website. Furthermore, the team created a brochure with the title “In 5 Schritten zum guten Klima” (LiLa4Green, n.d.) to summarise the smart participation methodology in five steps: 1. Prepare the ground and initiate the process, 2. Share knowledge and learn together, 3. Decide and create trust, 4. Designing the future in a playful way, and 5. Specify and implement together. Lastly, aiming to disseminate the knowledge and experiences with the scientific community, the research team actively participated in conferences, presentations, lectures and journals.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank Tanja Tötzer, expert advisor at the Austrian Institute of Technology in Vienna and coordinator of the LiLa4Green project, for the inspiring discussion and generous insights that have helped to write about LiLa4Green.

A.Pappa. ESR13

Read more

->

La Borda

Created on 16-10-2024

The housing crisis

After the crisis of 2008, it became obvious that the mainstream mechanisms for the provision of housing were failing to provide secure and affordable housing for many households, especially in the countries of the European south such as Spain. It is in this context that alternative forms emerged through social initiatives. La Borda is understood as an alternative form of housing provision and a tenancy form in the historical and geographical context of Catalonia. It follows mechanisms for the provision of housing that differ from predominant approaches, which have traditionally been the free market, with a for-profit and speculative role, and a very low percentage of public provision (Allen, 2006). It also constitutes a different tenure model, based on collective instead of private ownership, which is the prevailing form in southern Europe. As such, it encompasses the notions of community engagement, self-management, co-production and democratic decision-making at the core of the project.

Alternative forms of housing

In the context of Catalonia, housing cooperatives go back to the 1960s when they were promoted by the labour movement or by religious entities. During this period, housing cooperatives were mainly focused on promoting housing development, whether as private housing developers for their members or by facilitating the development of government-protected housing. In most cases, these cooperatives were dissolved once the promotion period ended, and the homes were sold.

Some of these still exist today, such as the “Cooperativa Obrera de Viviendas” in El Prat de Llobregat. However, this model of cooperativism is significantly different from the model of “grant of use”, as it was used mostly as an organizational form, with limited or non-existent involvement of the cooperative members.

It was only after the 2008 crisis, that new initiatives have arisen, that are linked to the grant-of-use model, such as co-housing or “masoveria urbana”. The cooperative model of grant-of-use means that all residents are members of the cooperative, which owns the building. As members, they are the ones to make decisions about how it operates, including organisational, communitarian, legislative, and economic issues as well as issues concerning the building and its use. The fact that the members are not owners offers protection and provides for non-speculative development, while actions such as sub-letting or transfer of use are not possible. In the case that someone decides to leave, the flat returns to the cooperative which then decides on the new resident. This is a model that promotes long-term affordability as it prevents housing from being privatized using a condominium scheme. The grant -of -use model has a strong element of community participation, which is not always found in the other two models. International experiences were used as reference points, such as the Andel model from Denmark and the FUCVAM from Uruguay, according to the group (La Borda, 2020). However, Parés et al. (2021) believe that it is closer to the Almen model from Scandinavia, which implies collective ownership and rental, while the Andel is a co-ownership model, where the majority of its apartments have been sold to its user, thus going again back to the free-market stock.

In 2015, the city of Barcelona reached an agreement with La Borda and Princesa 49, allowing them to become the first two pilot projects to be constructed on public land with a 75-year leasehold. However, pioneering initiatives like Cal Cases (2004) and La Muralleta (1999) were launched earlier, even though they were located in peri-urban areas. The main difference is that in these cases the land was purchased by the cooperative, as there was no such legal framework at the time. This means that these projects are classified as Officially Protected Housing (Vivienda de Protección Oficial or VPO), and thus all the residents must comply with the criteria to be eligible for social housing, such as having a maximum income and not owning property. Also, since it is characterised as VPO there is a ceiling to the monthly fee to be charged for the use of the housing unit, thus keeping the housing accessible to groups with lower economic power. This makes this scheme a way to provide social housing with the active participation of the community, keeping the property public in the long term. After the agreed period, the plot will return to the municipality, or a new agreement should be signed with the cooperative.

The neighbourhood movement

In 2011, a group of neighbours occupied one of the abandoned industrial buildings in the old industrial state of Can Batlló in response to an urban renewal project, with the intention of preserving the site's memory (Can Batlló, 2020; Girbés-Peco et al., 2020). The neighbourhood movement known as "Recuperem Can Batlló" sought to explore alternative solutions to the housing crisis of the time. The project started in 2012, after a series of informal meetings with an initial group of 15 people who were already active in the neighbourhood, including members of the architectural cooperative Lacol, members of the labour cooperative La Ciutat Invisible, members of the association Sostre Civic and people from local civic associations. After a long process of public participation, where the potential uses of the site were discussed, they decided to begin a self-managed and self-promotion process to create La Borda. In 2014 they legally formed a residents’ cooperative and after a long process of negotiation with the city council, they obtained a lease for the use of the land for 75 years in exchange for an annual fee. At that time, the group expanded, and it went from 15 members to 45. After another two years of work, construction started in 2017 and the first residents moved in the following year.

The participatory process

The word “participation” is sometimes used as a buzzword, where it refers to processes of consultation or manipulation of participants to legitimise decisions, leading it to become an empty signifier. However, by identifying the hierarchies that such processes entail, we can identify higher levels of participation, that are based on horizontality, reciprocity, and mutual respect. In such processes, participants not only have equal status in decision-making, but are also able to take control and self-manage the whole process. This was the case with La Borda, a project that followed a democratic participation process, self-development, and self-management. An important element was also the transdisciplinary collaboration between the neighbours, the architects, the support entities and the professionals from the social economy sector who shared similar ideals and values.

According to Avilla-Royo et al. (2021), greater involvement and agency of dwellers throughout the lifetime of a project is a key characteristic of the cooperative housing movement in Barcelona. In that way, the group collectively discussed, imagined, and developed the housing environment that best covered their needs in typological, material, economic or managerial terms. The group of 45 people was divided into different working committees to discuss the diverse topics that were part of the housing scheme: architecture, cohabitation, economic model, legal policies, communication, and internal management. These committees formed the basis for a decision-making assembly. The committees would adapt to new needs as they arose throughout the process, for example, the “architectural” committee which was responsible for the building development, was converted into a “maintenance and self-building” committee once the building was inhabited. Apart from the specific committees, the general assembly is the place, where all the subgroups present and discuss their work. All adult members have to be part of a committee and meet every two weeks. The members’ involvement in the co-creation and management of the cooperative significantly reduced the costs and helped to create the social cohesion needed for such a project to succeed.

The building

After a series of workshops and discussions, the cooperative group together with architects and the rest of the team presented their conclusions on the needs of the dwellers and on the distribution of the private and communal spaces. A general strategy was to remove areas and functions from the private apartments and create bigger community spaces that could be enjoyed by everyone. As a result, 280 m2 of the total 2,950 m2 have been allocated for communal spaces, accounting for 10% of the entire built area. These spaces are placed around a central courtyard and include a community kitchen and dining room, a multipurpose room, a laundry room, a co-working space, two guest rooms, shared terraces, a small community garden, storage rooms, and bicycle parking. La Borda comprises 28 dwellings that are available in three different typologies of 40, 50 and 76 m2, catering to the needs of diverse households, including single adults, adult cohabitation, families, and single parents. The modular structure and grid system used in the construction of the dwellings offer the flexibility to modify their size in the future.

The construction of La Borda prioritized environmental sustainability and minimized embedded carbon. To achieve this, the foundation was laid as close to the surface as possible, with suspended flooring placed a meter above the ground to aid in insulation. Additionally, the building's structure utilized cross-laminated timber (CLT) from the second to the seventh floors, after the ground floor made of concrete. This choice of material had the advantage of being lightweight and low carbon. CLT was used for both the flooring and the foundation The construction prioritized the optimization of building solutions through the use of fewer materials to achieve the same purpose, while also incorporating recycled and recyclable materials and reusing waste. Furthermore, the cooperative used industrialized elements and applied waste management, separation, and monitoring. According to the members of the cooperative (LaCol, 2020b), an important element for minimizing the construction cost was the substitution of the underground parking, which was mandatory from the local legislation when you exceed a certain number of housing units, with overground parking for bicycles. La Borda was the first development that succeeded not only in being exempt from this legal requirement but also in convincing the municipality of Barcelona to change the legal framework so that new cooperative or social housing developments can obtain an “A” energy ranking without having to construct underground parking.

Energy performance goals focused on reducing energy demands through prioritizing passive strategies. This was pursued with the bioclimatic design of the building with the covered courtyard as an element that plays a central role, as it offers cross ventilation during the warm months and acts as a greenhouse during the cold months. Another passive strategy was enhanced insulation which exceeds the proposed regulation level. According to data that the cooperative published, the average energy consumption of electricity, DHW, and heating per square meter of La Borda’s dwellings is 20.25 kWh/m², which is 68% less, compared to a block of similar characteristics in the Mediterranean area, which is 62.61 kWh/m² (LaCol, 2020a). According to interviews with the residents, the building’s performance during the winter months is even better than what was predicted. Most of the apartments do not use the heating system, especially the ones that are facing south. However, the energy demands during the summer months are greater, as the passive cooling system is not very efficient due to the very high temperatures. Therefore, the group is now considering the installation of fans, air-conditioning, or an aerothermal installation that could provide a common solution for the whole building. Finally, the cooperative has recently installed solar panels to generate renewable energy.

Social impact and scalability

According to Cabré & Andrés (2018), La Borda was created in response to three contextual factors. Firstly, it was a reaction to the housing crisis which was particularly severe in Barcelona. Secondly, the emergence of cooperative movements focusing on affordable housing and social economies at that time drew attention to their importance in housing provision, both among citizens and policy-makers. Finally, the moment coincided with a strong neighbourhood movement around the urban renewal of the industrial site of Can Batlló. La Borda, as a bottom-up, self-initiated project, is not just an affordable housing cooperative but also an example of social innovation with multiple objectives beyond providing housing.

The group’s premise of a long-term leasehold was regarded as a novel way to tackle the housing crisis in Barcelona as well as a form of social innovation. The process that followed was innovative as the group had to co-create the project, which included the co-design and self-construction, the negotiation of the cession of land with the municipality, and the development of financial models for the project. Rather than being a niche project, the aim of La Borda is to promote integration with the neighbourhood. The creation of a committee to disseminate news and developments and the open days and lectures exemplify this mission. At the same time, they are actively aiming to scale up the model, offering support and knowledge to other groups. An example of this would be the two new cooperative housing projects set up by people that were on the waiting list for la Borda. Such actions lead to the creation of a strong network, where experiences and knowledge are shared, as well as resources.

The interest in alternative forms of access to housing has multiplied in recent years in Catalonia and as it is a relatively new phenomenon it is still in a process of experimentation. There are several support entities in the form of networks for the articulation of initiatives, intermediary organizations, or advisory platforms such as the cooperative Sostre Civic, the foundation La Dinamo, or initiatives such as the cooperative Ateneos, which were recently promoted by the government of Catalonia. These are also aimed at distributing knowledge and fostering a more inclusive and democratic cooperative housing movement. In the end, by fostering the community’s understanding of housing issues, and urban governance, and by seeking sustainable solutions, learning to resolve conflicts, negotiate and self-manage as well as developing mutual support networks and peer learning, these types of projects appear as both outcomes and as drivers of social transformation.

Z.Tzika. ESR10

Read more

->

DARE to Build, Chalmers University of Technology

Created on 04-07-2023

'DARE to build' is a 5–week (1 week of design – 4 weeks of construction) elective summer course offered at the Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden. The course caters for master-level students from 5 different master programmes offered at the Architecture and Civil Engineering Department. Through a practice-based approach and a subsequent exposure to real-world problems, “DARE to build” aims to prove that “real change can be simultaneously made and learned (Brandão et al., 2021b, 2021a). The goal of this course is to address the increasing need for effective multidisciplinary teams in the fields of architecture, engineering and construction (AEC) in order to tackle the ever-growing complexity of real-world problems (Mcglohn et al., 2014), and the pervading lack of a strong pedagogical framework that responds effectively to this challenge. The two main foci of the “DARE to build” pedagogical model are: (1) to train students in interdisciplinary communication, to cultivate empathy and appreciation for the contributions of each discipline, to sharpen collaborative skills (Tran et al., 2012) and (2) to expose students in practice-based, real-world design projects, through a problem-and-project-based learning (PPBL) approach, within a multi-stakeholder learning environment (Wiek et al., 2014). This multi-stakeholder environment is situated in the municipality of Gothenburg and involves different branches and services (Stadsbyggnadskontoret, Park och Naturförvaltningen), local/regional housing companies (Familjebostäder, Bostadsbolaget), professionals/collectives operating within the AEC fields (ON/OFF Berlin, COWI), and local residents and their associations (Hyresgästföreningen, Tidsnätverket i Bergsjön).

Design & Build through CDIO

By showcasing that “building, making and designing are intrinsic to each other” (Stonorov et al., 2018, p. 1), students put the theory acquired into practice and reflect on the implications of their design decisions. Subsequently they reflect on their role as AEC professionals, in relation to local and global sustainability; from assessing feasibility within a set timeframe to the intangible qualities generated or channelled through design decisions in specific contexts. This hands-on learning environment applies the CDIO framework (conceive, design, implement, operate, http://www.cdio.org/), an educational framework developed in the MIT, with a particular focus on the “implementation” part. CDIO has been developed in recent years as a reforming tool for engineering education, and is centred on three main goals: (1) to acquire a thorough knowledge of technical fundamentals, (2) to sharpen leadership and initiative-taking skills, and (3) to become aware of the important role research and technological advances can play in design decisions (Crawley et al., 2014). Therefore, design and construction, combined with CDIO, offer a comprehensive experience that enables future professionals to assume a knowledgeable and confident role within the AEC sector.

Course structure

“DARE to build” projects take place during the autumn semester along with the “Design and Planning for Social Inclusion” (DPSI) studio. Students work closely with the local stakeholders throughout the semester and on completion of the studio, one project is selected to become the “DARE to build” project of the year, based on (1) stakeholder interest and funding capacity, (2) pedagogical opportunities and the (3) feasibility of construction. During the intervening months, the project is further developed, primarily by faculty, with occasional inputs from the original team of DPSI students and support from professionals with expertise relevant to a particular project. The purpose of this further development of the initial project is to establish the guidelines for the 1-week design process carried out within “DARE to build”.

During the building phase, the group of students is usually joined by a team of 10-15 local (whenever possible) summer workers, aged between 16-21 years old, employed by the stakeholders (either by the Municipality of Gothenburg or by a local housing company). The aim of this collaboration is twofold - to have a substantial amount of workforce on site and to create a working environment where students are simultaneously learning and teaching, therefore enhancing their sense of responsibility. “DARE to build” has also collaborated - in pre-pandemic times - with Rice University in Texas, so 10 to 15 of their engineering students joined the course as a summer educational experience abroad.

The timeline for each edition of the “DARE to build” project evolution can be schematically represented through the CDIO methodology, which becomes the backbone of the programme (adapted from the courses’ syllabi):

Conceive: Developed through a participatory process within the design studio “Design and Planning for Social Inclusion”, in the Autumn.

Design: (1) Teaching staff defines design guidelines and materials, (2) student participants detail and redesign some elements of the original project, as well as create schedules, building site logistical plans, budget logs, etc.

Implement: The actual construction of the building is planned and executed. All the necessary building documentation is produced in order to sustain an informed and efficient building process.

Operate: The completed built project is handed over to the stakeholders and local community. All the necessary final documentation for the operability of the project is produced and completed (such as-built drawings, etc.).

In both the design and construction process, students take on different responsibilities on a daily basis, in the form of different roles: project manager, site supervisor, communications officer, and food & fika (=coffee break) gurus. Through detailed documentation, each team reports on everything related to the project’s progress, the needs and potential material deficits on to the next day’s team. Cooking, as well as eating and drinking together, works as an important and an effective team-bonding activity.

Learning Outcomes

The learning outcomes are divided into three different sets to fit with the overall vision of “DARE to Build” (adapted from the course syllabi):

Knowledge and understanding: To identify and explain a project’s life cycle, relate applied architectural design to sustainability and to describe different approaches to sustainable design.

Abilities and skills: To be able to implement co-creation methods, design and assess concrete solutions, to visualise and communicate proposals, to apply previously gained knowledge to real-world projects, critically review architectural/technical solutions, and to work in multidisciplinary teams.

Assessment and attitude: To be able to elaborate different proposals on a scientific and value-based argumentation, to combine knowledge from different disciplines, to consider and review conditions for effective teamwork, to further develop critical thinking on professional roles.

The context of operations: Miljonprogrammet

The context in which “DARE to Build” operates is the so-called “Million Homes Programme” areas (MHP, in Swedish: Miljonprogrammet) of suburban Gothenburg. The MHP was an ambitious state-subsidised response to the rapidly growing need for cheap, high-quality housing in the post-war period. The aim was to provide one million dwellings within a decade (1965-1974), an endeavour anchored on the firm belief that intensified housing production would be relevant and necessary in the future (Baeten et al., 2017; Hall & Vidén, 2005). During the peak years of the Swedish welfare state, as this period is often described, public housing companies, with help from private contractors, built dwellings that targeted any potential home-seeker, regardless of income or class. In order to avoid suburban living and segregation, rental subsidies were granted on the basis of income and number of children, so that, in theory, everyone could have access to modern housing and full of state-of-the-art amenities (Places for People - Gothenburg, 1971).

The long-term perspective of MHP also meant profound alterations in the urban landscape; inner city homes in poor condition were demolished and entire new satellite districts were constructed from scratch triggering “the largest wave of housing displacement in Sweden’s history, albeit firmly grounded in a social-democratic conviction of social betterment for all” (Baeten et al., 2017, p. 637) . However, when this economic growth came to an abrupt halt due to the oil crisis of the 1970s, what used to be an attractive and modern residential area became second-class housing, shunned by the majority of Swedish citizens looking for a house. Instead, they became an affordable option for the growing number of immigrants arriving in Sweden between 1980 and 2000, resulting in a high level of segregation in Swedish cities. (Baeten et al., 2017).

Nowadays, the MHP areas are home to multi-cultural, mostly low income, immigrant and refugee communities. Media narratives of recent decades have systematically racialised, stigmatised and demonised the suburbs and portrayed them as cradles of criminal activity and delinquency, laying the groundwork for an increasingly militarised discourse (Thapar-Björkert et al., 2019). The withdrawal of the welfare state from these areas is manifested through the poor maintenance of the housing stock and the surrounding public places and the diminishing public facilities (healthcare centres, marketplaces, libraries, etc.) to name a few. Public discourse, best reflected in the media, often individualizes the problems of "culturally different" inhabitants, which subsequently "justifies" people's unwillingness to work due to the "highly insecure" environment.

In recent years, the gradual (neo)liberalisation of the Swedish housing regime has provided room for yet another wave of displacement, leaving MHP area residents with little to no housing alternatives. The public housing companies that own MHP stock have started to offer their stock to potential private investors through large scale renovations that, paired with legal reforms, allow private companies to reject rent control. As a result, MHP areas are entering a phase of brutal gentrification (Baeten et al., 2017).

Reflections

Within such a sensitive and highly complex context, both “DARE to Build”, and “Design & Planning for Social Inclusion” aspire to make Chalmers University of Technology an influential local actor and spatial agent within the shifting landscape of the MHP areas, thus highlighting the overall relevance of academic institutions as strong, multi-faceted and direct connections with the “real-world”.

Even though participation and co-creation methodologies are strong in all “Design and Planning for Social Inclusion” projects, “DARE to Build” has still some ground to cover. In the critical months that follow the selection of the project and up to the first week of design phase, a project may change direction completely in order to fit the pedagogical and feasibility criteria. This fragmented participation and involvement, especially of those with less power within the stakeholder hierarchy, risks leading to interventions in which local residents have no sense of ownership or pride, especially in a context where interventions from outsiders, or from the top down, are greeted with increased suspicion and distrust.

Overall “DARE to build” is a relevant case of context-based education which can inform future similar activities aimed at integration education in the community as an instrument to promote sustainable development.

Relevant “DARE to build” projects

Gärdsåsmosse uteklassrum: An outdoor classroom in Bergsjön conceptualised through a post-humanist perspective and constructed on the principles of biomimicry, and with the use of almost exclusively natural materials.

Visit: https://www.chalmers.se/sv/institutioner/ace/nyheter/Sidor/Nu-kan-undervisningen-dra-at-skogen.aspx

https://www.mynewsdesk.com/se/cowi/pressreleases/cowi-hjaelpte-goeteborgs-stad-foervandla-moerk-park-till-en-plats-att-ha-picknick-i-2920358

Parkourius: A parkour playground for children and teens of the Merkuriusgatan neighbourhood in Bergsjön. A wooden construction that employs child-friendly design.

Visit: https://www.sto-stiftung.de/de/content-detail_112001.html https://www.mynewsdesk.com/se/familjebostader-goteborg-se/pressreleases/snart-invigs-bergsjoens-nya-parkourpark-3111682

E.Roussou. ESR9

Read more

->

Marmalade Lane

Created on 08-06-2022

Background

An aspect that is worth highlighting of Marmalade Lane, the biggest cohousing community in the UK and the first of its kind in Cambridge, is the unusual series of events that led to its realisation. In 2005 the South Cambridgeshire District Council approved the plan for a major urban development in its Northwest urban fringe. The Orchard Park was planned in the area previously known as Arbury Park and envisaged a housing-led mix-use master plan of at least 900 homes, a third of them planned as affordable housing. The 2008 financial crisis had a profound impact on the normal development of the project causing the withdrawal of many developers, with only housing associations and bigger developers continuing afterwards. This delay and unexpected scenario let plots like the K1, where Marmalade Lane was erected, without any foreseeable solution. At this point, the city council opened the possibilities to a more innovative approach and decided to support a Cohousing community to collaboratively produce a brief for a collaborative housing scheme to be tendered by developers.

Involvement of users and other stakeholders

The South Cambridgeshire District Council, in collaboration with the K1 Cohousing group, ventured together to develop a design brief for an innovative housing scheme that had sustainability principles at the forefront of the design. Thus, a tender was launched to select an adequate developer to realise the project. In July 2015, the partnership formed between Town and Trivselhus ‘TOWNHUS’ was chosen to be the developer. The design of the scheme was enabled by Mole Architects, a local architecture firm that, as the verb enable indicates, collaborated with the cohousing group in the accomplishment of the brief. The planning application was submitted in December of the same year after several design workshop meetings whereby decisions regarding interior design, energy performance, common spaces and landscape design were shared and discussed.

The procurement and development process was eased by the local authority’s commitment to the realisation of the project. The scheme benefited from seed funding provided by the council and a grant from the Homes and Communities Agency (HCA). The land value was set on full-market price, but its payment was deferred to be paid out of the sales and with the responsibility of the developer of selling the homes to the K1 Cohousing members. Who, in turn, were legally bounded to purchase and received discounts for early buyers.

As relevant as underscoring the synergies that made Marmalade Lane’s success story possible, it is important to realise that there were defining facts that might be very difficult to replicate in order to bring about analogue housing projects. Two major aspects are securing access to land and receiving enough support from local authorities in the procurement process. In this case, both were a direct consequence of a global economic crisis and the need of developing a plot that was left behind amidst a major urban development plan.

Innovative aspects of the housing design

Spatially speaking, the housing complex is organised following the logic of a succession of communal spaces that connect the more public and exposed face of the project to the more private and secluded intended only for residents and guests. This is accomplished by integrating a proposed lane that knits the front and rear façades of some of the homes to the surrounding urban fabric and, therefore, serves as a bridge between the public neighbourhood life and the domestic everyday life. The cars have been purposely removed from the lane and pushed into the background at the perimeter of the plot, favouring the human scale and the idea of the lane as a place for interaction and encounters between residents. A design decision that depicts the community’s alignment with sustainable practices, a manifesto that is seen in other features of the development process and community involvement in local initiatives.

The lane is complemented by numerous and diverse places to sit, gather and meet; some of them designed and others that have been added spontaneously by the inhabitants offering a more customisable arrangement that enriches the variety of interactions that can take place. The front and rear gardens of the terraced houses contiguous to the lane were reduced in surface and remained open without physical barriers. A straightforward design decision that emphasises the preponderance of the common space vis-a-vis the private, blurring the limits between both and creating a fluid threshold where most of the activities unfold.

The Common House is situated adjacent to the lane and congregates the majority of the in-doors social activities in the scheme, within the building, there are available spaces for residents to run community projects and activities. They can cook in a communal kitchen to share both time and food, or organise cinema night in one of the multi-purpose areas. A double-height lounge and children's playroom incite gathering with the use of an application to organise easily social events amongst the inhabitants. Other practical facilities are available such as a bookable guest bedroom and shared laundry. The architecture of its volume stands out due to its cubic-form shape and different lining material that complements its relevance as the place to convene and marks the transition to the courtyard where complementary outdoor activities are performed. Within the courtyard, children can play without any danger and under direct supervision from adults, but at the same time enjoy the liberty and countless possibilities that such a big and open space grants.

Lastly, the housing typologies were designed to recognise multiple ways of life and needs. Consequently, adaptability and flexibility were fundamental targets for the architects who claim that units were able to house 29 different configurations. They are arranged in 42 units comprehending terraced houses and apartments from one to five bedrooms. Residents also had the chance to choose between a range of interior materials and fittings and one of four brick colours for the facade.

Construction and energy performance characteristics

Sustainability was a prime priority to all the stakeholders involved in the project. Being a core value shared by the cohousing members, energy efficiency was emphasised in the brief and influenced the developer’s selection. The Trivselhus Climate Shield® technology was employed to reduce the project’s embodied and operational carbon emissions. The technique incorporates sourced wood and recyclable materials into a timber-framed design using a closed panel construction method that assures insulation and airtightness to the buildings. Alongside the comparative advantages of reducing operational costs, the technique affords open interior spaces which in turn allow multiple configurations of the internal layout, an aspect that was harnessed by the architectural design. Likewise, it optimises the construction time which was further reduced by using industrialised triple-glazed composite aluminium windows for easy on-site assembly. Furthermore, the mechanical ventilation and heat recovery (MVHR) system and the air source heat pumps are used to ensure energy efficiency, air quality and thermal comfort. Overall, with an annual average heat loss expected of 35kWh/m², the complex performs close to the Passivhaus low-energy building standard of 30kWh/m² (Merrick, 2019).

Integration with the wider community

It is worth analysing the extent to which cohousing communities interact with the neighbours that are not part of the estate. The number of reasons that can provoke unwanted segregation between communities might range from deliberate disinterest, differences between the cohousing group’s ethos and that one of the wider population, and the common facilities making redundant the ones provided by local authorities, just to name a few. According to testimonies of some residents contacted during a visit to the estate, it is of great interest for Marmalade Lane’s community to reach out to the rest of the residents of Orchard Park. Several activities have been carried out to foster integration and the use of public and communal venues managed by the local council. Amongst these initiatives highlights the reactivation of neglected green spaces in the vicinity, through gardening and ‘Do it yourself’ DIY activities to provide places to sit and interact. Nonetheless, some residents manifested that the area’s lack of proper infrastructure to meet and gather has impeded the creation of a strong community. For instance, the community centre run by the council is only open when hired for a specific event and not on a drop-in basis. The lack of a pub or café was also identified as a possible justification for the low integration of the rest of the community.

Marmalade Lane residents have been leading a monthly ‘rubbish ramble’ and social events inviting the rest of the Orchard Park community. In the same vein, some positive impact on the wider community has been evidenced by the residents consulted. One of them mentioned the realisation of a pop-up cinema and a barbecue organised by neighbours of the Orchard Park community in an adjacent park. Perhaps after being inspired by the activities held in Marmalade Lane, according to another resident.

L.Ricaurte. ESR15

Read more

->

The Elwood Project, Vancouver, Washington

Created on 25-01-2024

The Elwood Project is an affordable housing development and includes forty-six apartments and supportive housing services provided by Sea-Mar Community Services. All apartments are subsidised through the Vancouver Housing Authority, so that tenants pay thirty-five percent of their income towards rent, according to public housing designation. There are garden-style apartments to allow residents to choose when and where to interact with neighbours. Units are 37 sq. m. with 1 bedroom. These apartments are fully accessible and amenities include a community room, laundry room, covered bike parking, and outdoor courtyard with a community garden (Housing Initiative, 2022).

This case highlights the benefits of trauma informed design (TID) in the supportive housing sector. These homes were built using concepts of open corridors, natural light, art and nature, colours of nature, natural materials, design with commercial sustainability, elements of privacy and personalization, open areas, adequate and easy access to services. With these thoughtful techniques, Elwood offers socially sustainable help for vulnerable people (people with special needs, homeless, formally homeless) and for the new “housing precariat”.

The Elwood project is a good example of combining private apartments with opportunities for community living, where services and facilities management contribute to the well-being and stability of dwellers. What makes this project especially unique is that it does not look like affordable housing. As Brendan Sanchez concluded, people think that it “looks like really nice market rate upscale housing”, which is empowering, because people in general “deserve access to quality-built environment and healthy indoor interior environments”. Access Architecture did not design it as affordable housing, they just “designed it as housing” (Access Architecture, 2022).

Affordability aspects

The Elwood affordable housing community project is in a commercially zoned transit corridor. Existing planning regulations did not allow building permits in this area. Elwood is the first affordable housing development in the city of Vancouver that has required changes to the city’s zoning regulations. As a result of these changes, other measures have been adopted to promote affordable housing in the community. Under the city's previous building regulations, it was simply not possible to obtain a building permit. The Affordable Housing Fund helped developers to undertake this project and provided tenants with budget friendly housing options (Otak, 2022).

Now, thanks to the Elwood project, there are ongoing talks at the Board of the Planning Commission of Elwood Town to get construction permits for similar projects. As the council stated, “it is on the horizon for all towns to have affordable housing” (Elwood Town Corporation, 2022). Although the population of the area is small, it is estimated that in the coming years the need for more affordable housing units will increase. Previously, permitted uses were limited to C-2 (general commercial, office and retail) and C-3 (intensive service commercial) zoning uses (e.g., gas station, restaurant, public utility substation). Currently, the members of the town council together with other stakeholders are negotiating new plans for affordable housing in the area. With the help of the community, they are striving to harmonise the legal, political, financial and design aspects and work on a general plan that includes the construction of multi-family affordable dwellings. In addition, the ultimate goal is to further modify zoning regulations to incorporate tax advantages for social housing.

Sustainability aspects

It is a highly energy efficient building as it meets the minimum requirements of the Evergreen Sustainable Development Standards (ESDS), which include requirements for low Volatile Organic Compounds (VOC) content, water conservation, air sealing, and reduction of thermal bridges. It also meets the Green Point Rated Program requirements. The building materials are bamboo, cork, salvaged or FSC-Certified wood, natural linoleum, natural rubber and ceramic tile. There are no VOC adhesives or synthetic backing in living rooms, and bathrooms (Otak, 2022).

Design

Access Architecture used an outcome-based design process during the development of this project.

The outcome-based design process considers TID principles to lower barriers among tenants and minimize stigma of receiving services. Brendan Sanchez from Access Architecture highlights that TID is a kind of design that is “getting a lot more attention now that people understand it more. It applies in this project, and we’re also just finding that it doesn’t have to be a certain traumatic event we design for. It can also be a systemic problem — we all have our own traumas we’re working through, especially after the events of the pandemic last year. So Access likes to focus on how we can create healing spaces in this kind of design.” (Nichiha, 2022)

As Di Raimo et al. (2021) wrote, trauma informed approaches can be adopted by a wide range of service providers (health, social care, education, justice). In this case, Sea Mar-Community Services Northwest’s Foundational Community Support provides guidance for tenants with the help of case managers. Such partners can help with professional and health objectives. CDM Caregiving Services helps (or offer assistance) with daily tasks from cooking to cleaning and hygiene. Finally, Vancouver Housing Authority members help with anything they can, so that tenants would not feel themselves alone with their problems (Nahro, 2022).

Elwood offers informal indoor and outdoor spaces which provide a relaxed atmosphere in a friendly milieu. In this building, TID suits the resident’s needs. The building was planned with the help of potential residents and social workers, so that a sense of space and place would provide familiarity, stability, and safety for those who are longing for the feeling of place attachment.

A.Martin. ESR7

Read more

->

Navarinou Park

Created on 03-10-2023

Background

The neighbourhood of Exarcheia, where the park is located, is one of the most – if not the most– politically active areas in Athens and is traditionally home to intellectuals and artists. Since the 1970s, it has been in the centre of social movements, serving as a breeding ground for leftist, anarchist and antifascist grassroots and alternative cultural practices (Chatzidakis, 2013). Given its location in the centre of Athens, the neighbourhood is lacking green and open spaces.

The site of the park has a long history of negotiations regarding ownership and use, dating back to the 1970s. During that time, the Technical Chamber of Greece (TEE) purchased the 65-year-old medical clinic with the purpose of demolishing it and constructing its central offices. Although the building was eventually demolished in the 1980s, TEE never constructed its offices. In the 1990s, the site was offered as part of an exchange between the TEE and the Municipality of Athens for the development of a green space, but this agreement did not materialise. Instead, the TEE leased the plot for private use, and turned it into an open-air parking space (Frezouli, 2016).

The termination of the lease in 2008 coincided with a major social movement triggered by the assassination of a 15-year-old boy, Alexis Grigoropoulos, at the hands of the police. This tragic incident took place in December of the same year, just a few streets away from the site and led to uprisings in many Greek cities and neighbourhoods as citizens demanded the right to life, freedom, and the city through protests and illegal occupations. In response to the rumours about the site’s future construction, the Exarcheia Residents’ Initiative, in collaboration with many grassroots movements, used digital means to issue a collective call for action to reclaim the plot as an open green space. On 7th March 2009, tens of people from the neighbourhood and around Athens occupied the plot and created the 'Self-managed Navarinou and Zoodochou Pigis Park' (Frezouli, 2016; pablodesoto, 2010)

The park as an urban commons urban commons resource

The operation and development of the park, in terms of its uses and infrastructure, is collectively shaped by the appropriating community of commoners, consisting of activists and local residents, without any contributions from the state, municipal or private organisations. Hence the activities and interventions within the park are evolving with the joint efforts and time, work, skills and financial resources of the commoners.

In this regard, the transformation of the space from a parking lot into its present form has followed a dynamic process, that keeps adapting to the changing resources, needs and challenges created by the social and urban circumstances. The initial intervention involved replacing the concrete ground with soil and planting flowers and trees donated by the community. Subsequently, a small playground and seating areas were constructed, forming an open amphitheatre (Parko Navarinou Initative, 2018b). This infrastructure served as a base for organising public events such as cultural activities, public discussions, live concerts, film projections, and children’s activities. At a later stage, educational workshops on agriculture were also introduced (Frezouli, 2016). Many of the activities brought about spatial transformations within the park, including the creation of community gardens or sculptures, murals and installations.

In its most recent phase, the park has been transformed into a “big playground” for all the residents housing a variety of greenery, such as the urban gardens, as well as seating and gathering urban furniture, including benches and tables. The park now features several playground equipment suitable for both children and adults, such as swings, playing structures, a basketball court, and a ping pong table. Additionally, safety has been enhanced by improving the lighting and adding a fence (Parko Navarinou Initative, 2018a).

Commoners and commoning

To thrive as a bottom-up initiative, the operation and governance of the park are based on several forms of mobilisation that extend beyond the initial public space occupation. Among the various forms of commoning undertaken, activism, collective action, network creation and co-governance have been vital for Navarinou Park. These social processes have been supported by other participatory or community-based practices, such as public campaigns, co-construction and co-creation activities (Frezouli, 2016).

Since its beginning, the initiative has established an open assembly as the main instrument for decision-making on operational and infrastructural matters related to the park. This ensures that the park remains a shared resource, fostering a sense of belonging and strong bonds among the commoners. The assembly sets the rules and practises that constitute the institutional arrangements of the park, following a governance model based on horizontal democratic processes driven by the principles of self-management, anti-hierarchy and anti-commodification. The assembly is open to any individual or group that wishes to participate. However, throughout the park’s lifetime, only a small core of people remains permanently committed to the initiative. This groups is cohesive in terms of social incentives, activist ideals, and social capital, which reduces conflicts during decision-making processes (Arvanitidis & Papagiannitsis, 2020).

However, beyond addressing issues such as maintenance, organisation of events and infrastructure interventions, the assembly has been confronted with several challenges of both internal and external character, necessitating adaptability and rule-setting. One key challenge is the continuous commitment required for attending meetings and carrying out the daily tasks, which relies entirely on voluntary engagement. The gradual decrease in engagement, reaching its peak in early 2018 and even threatening the park’s survival, prompted the core team to seek new forms of communication and involvement to attract more residents to use and engage with the space. (Arvanitidis & Papagiannitsis, 2020). The idea that emerged focused on addressing the lack of play-areas in the neighbourhood by transforming the park into a large playground that would appeal to families, parents, children and the elderly. This vision was realised through a successful crowdfunding campaign (Parko Navarinou Initative, 2018a) that used the moto “play, breath, discuss, blossom, reclaim, live” to convey the key functions of the park.

Another significant challenge, especially during the first years of the initiative, was external delinquent behaviour, including vandalism, drug trafficking, and problems with the police (Avdikos, 2011). After several negotiations, the assembly decided to install a fence around the park to improve the monitoring and maintenance of the space while still keeping it open to everyone during operational hours and activities.

Impact & Significance

Navarinou Park is considered to be a successful example of the bottom-up transformation of an urban void into an urban commons among scholarly discourses (Arvanitidis & Papagiannitsis, 2020; Daskalaki, 2018; Frezouli, 2016; pablodesoto, 2010). It not only provides environmental benefits delivered through high quality green spaces, along with a variety of social and cultural activities for the residents of Exarcheia but, most significantly, it has "motivated and empowered residents, offering a great sense of pride and providing incentives for enhancing social capital and social inclusion, community resilience, collective learning and action"(Daskalaki, 2018, p. 162). The park demonstrates a successful example of urban commons in continuous growth, where social capital and solidarity are the motivating goals that drive both collective management and the ability to overcome challenges over time:

“If there is one thing that motivates us to move forward, it is the impact of our endeavour not only in theory but in practice: in the constructive transformation of behaviours, awarenesses, practices and everyday lives. It is up to us to seize the new opportunities that open up before us. If we ourselves do not struggle to create the utopias we imagine, they will never exist”. (Parko Navarinou Initative, 2018a)

A.Pappa. ESR13

Read more

->

Mehr als wohnen – More than housing

Created on 21-10-2024

The context

In Switzerland, housing cooperatives are private organisations, co-owned and self-managed. The city of Zurich has a rich history of housing cooperatives and non-profit housing associations dating back to the early 20th century, constituting 25% of the city’s housing stock. As was the case in other central European cities, housing cooperatives in Zurich emerged in response to a housing shortage and the unavailability of affordable prices. The model for establishing a housing cooperative is straightforward: individuals come together to form a cooperative, becoming shareholders. The cooperative builds housing and rents it to its members at cost prices. Since no profits are generated, and the land value is not increased for resale, the gap between cooperative rents and open market rents widens significantly over time. Historically, members of housing cooperatives were often affiliated based on profession or religion, such as public officers, for example.

The foundation of this housing cooperative model was laid in 1907 when a law was enacted, assigning responsibility to the municipality for providing ‘affordable and adequate housing’ (Hugentobler et al., 2016). The first housing cooperatives were established in 1910, and the Allgemeine Baugenossenschaft Zürich, ABZ, currently the largest cooperative in Switzerland, was founded in 1916. In the 1970s, cooperative housing faced a decline due to poor maintenance. However, a revival occurred in the 1980s when a new cooperative movement emerged. The new cooperatives aimed to break away from the rigidity, institutionalisation, and outdated principles of traditional housing cooperatives. The discourse of this movement emphasized the need for more sustainable living environments, affordable and non-speculative housing, and social integration. In 2011, a city-scale referendum took place, resulting in the population voting in favour of a law aiming to increase the proportion of non-profit housing to 33% of all housing (not just newly built homes) in the city by 2050. This legislation mandates the city of Zurich to establish a framework and instruments to support non-profit housing.

Process

In 2008, the Public Works Department of the city of Zurich and the cooperative Mehr als Wohnen launched an international competition for ideas. This initiative was part of the festivities marking 100 years since the inception of cooperative housing in Zurich (“Mehr als wohnen - 100 Jahre gemeinnütziger Wohnungsbau”). The competition sought innovative ideas about the future of non-profit housing. Out of 100 submissions, 26 teams of architects were selected and were invited to submit an urban development concept for the Hunziker Areal, including designs for residential buildings. A young team won the master plan competition, aiming to integrate diverse architectural proposals into a cohesive urban development concept. A subsequent dialogue phase ensued, during which architects and project operators collaborated to integrate various concepts into the master plan. Future residents and the broader public participated in 3 to 4 events annually, engaging in discussions about the neighbourhood’s future. The dialogic process continued until construction started in 2012.

Land

The four-hectare plot of disused industrial land at the Hunziker Areal in the Leutschenbach district was made available for building by the city administration. The site formerly housed a concrete industry until the 1980s when the company closed, and the city of Zurich acquired the land. Due to a law approved by a referendum in 2011, the city of Zurich is obligated to prioritize non-profit housing over selling land to the highest bidder. In 2007, the city council signed an agreement with the cooperative for a lease of 100 years, with the possibility of renewal. As part of the agreement, the cooperative must adhere to various conditions, including calculating rents based on investment costs, subsidizing 20% of the housing units, providing 1% of the ground floor for neighbourhood services at no cost to the city, allocating 0,5% of construction costs to local art projects, meeting high energy standards in construction, and launching an architectural competition for the new housing buildings. The cooperative pays an annual fee for the use of the plot, which is adjusted every five years, according to the cost-of-living index and interest rates. This fee also considers the space provided by the cooperative and the subsidies offered to low-income residents.

Funding

Following the agreement with the city council for the land, cooperative members embarked on securing funding. The members of the cooperative had to bring the 5,4% of the initial capital, with the remaining other 0.6% covered by the municipality. The founding cooperatives of Mehr als Wohnen leveraging their existing resources and expertise, contributed half of this amount. The other half was covered by the future residents, amounting to CHF 250/m2 as their member equity. For low-income households or elderly people, the city’s social services could cover this amount.

The remaining funding was obtained from three levels of administration: city, canton and federal. At the federal level, the Federation of Swiss Housing Cooperatives provided a CHF 11 million loan through its revolving fund, offering a twenty-year term with a 1% interest rate. Additionally, at the federal level, CHF 35 million was secured through a bond loan with fixed interest rates for the first twenty years, facilitated by the Bond Issuing Cooperative for Limited Profit Housing (Emissionszentrale für gemeinnütziger Wohnbauträger/ Centrale d’émission pour la construction de logements – EGW/CC) and public subsidies. EGW functions as a financing instrument for housing projects of public interest, guaranteeing loans through the Swiss Confederation (Federal Bureau of Housing) to provide security for investors. Nonprofits benefit from significantly more advantages compared to comparable fixed mortgages with the same terms. At the cantonal level of Zurich, the project secured a CHF 8 million loan, and at the municipal level, another of CHF 8 million, both with fixed interest rates. However, instead of paying the interest to the city and canton of Zurich, the cooperative uses this amount to subsidize 20% of housing units (80 of the 370 apartments). To complete its financial planning, Mehr als Wohnen also secured a CHF 8 million loan from the city of Zurich’s pension fund, with a fixed interest rate. With this combination of sources, providing 27% of the total investments, the remaining necessary financing was obtained from a consortium of four banks through traditional mortgage loans.

Inclusion mechanisms

Mehr als Wohnen employs a mechanism commonly used by many Swiss housing cooperatives, that allows its members to transfer their savings to the cooperative instead of keeping them in traditional banks. These “member funds” constitute part of the cooperative’s capital, meaning that the larger the member funds are, the less the cooperative will rely on mortgages in the future. Members who invest in their cooperatives benefit from a higher investment return compared to what they would receive at a conventional bank. The cooperative also maintains an internal solidarity fund, aiding in financing solidarity projects or assisting families facing difficulties in paying their equity. Every household and commercial store contributes a monthly amount, ranging from 10 to 30 CHF, depending on their income. Through this fund, the cooperative can reduce monthly rents for low-income households, cover maintenance or adaptation fees, organise events, and provide financial support to cooperative projects in the neighbourhood or abroad.

Design innovations