ESG finance and social housing decarbonisation

Created on 05-02-2024 | Updated on 05-02-2024

The regulation of financial markets according to Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) criteria has become a priority for the European Union (EU). Recent legislation, such as the EU Green Taxonomy, aims to identify sustainable investments enhancing transparency and accountability while steering private finance toward environmental objectives. The introduction of ESG criteria poses specific questions for Social Housing Organisations (SHOs), particularly as the decarbonisation of the housing stock is also incorporated into the national legislation of Member States. This case study analyses ESG finance in the context of social housing, examining the main legislative changes and their impact on social housing provision systems in abstract. For more detailed information, readers are invited to read the full-paper published in the Journal of Housing Studies. Link.

Instrument

Regulation

Issued (year)

2020s

Application period (years)

2020s

Scope

European-Global

Target group

NA

Housing tenure

NA

Discipline

economics-sociology-finance

Object of study

Instrument

Description

Over the last decades, ESG debt issuance, through green, social or sustainability-linked loans and bonds has become increasingly common. Financial markets have hailed the adoption of ESG indicators as a tool to align capital investments with environmental and social goals, such as the decarbonisation of the social housing stock. According to the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), the green debt market has experienced a 50% growth over the last five years (CBI, 2021). However, the lack of clearly established indicators and objectives has tainted the growth of green finance with a series of high-level scandals and accusations of green-washing, unjustified claims of a company’s green credentials. For example, a fraud investigation by German prosecutors into Deutsche Bank’s asset manager, DWS, has found that ESG factors were not taken into account in a large number of investments despite this being stated in the fund’s prospectus (Reuters, 2022).

To curb greenwashing and improve transparency and accountability in green investments, the EU has embarked on an ambitious legislative agenda. This includes the first classification of environmentally sustainable economic activities: the EU Green Taxonomy (Regulation 2020/852). The Taxonomy is directly linked to the European Commission’s decarbonisation strategy, the Renovation Wave (COM (2020) 662), which relies on a combination of private and public finance to secure the investment needed for the decarbonisation of social housing.

Energy efficiency targets have become increasingly stringent as the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) and its successive recasts (COM(2021)) have been incorporated into national legislation; see for example the French Loi Climate et Resilience (2021-1104, 2021). Consequently, capital expenses for SHOs are set to increase considerably. For example, in the Netherlands, according to a Housing Europe (2020) report, attaining the 2035 energy efficiency targets set by the Dutch government will cost €116bn.

Sustainable finance legislation constitutes an expansion of the financial measures implemented by the EU in recent decades to incentivise energy efficiency standards as well as renovations in the built environment. For more detail on prior EU policies, see Economidou et al. (2020) and Bertoldi et al. (2021). The increased connections between finance and energy performance raise specific questions regarding SHOs’ access to capital markets in light of the shift toward ESG.

The rapidly expanding finance literature on green bonds draws from econometric models to explore the links between investors’ preferences and yields (Fama & French, 2007). This body of literature on asset pricing relies on the introduction of non-pecuniary preferences in investors’ utility functions together with returns and risks to explain fluctuations in the equilibrium price of capital. Drawing from a comparison between green and conventional bonds, Hachenberg and Schiereck (2018) find evidence of the former being priced at a premium. Similarly, Zerbib (2019) also shows a low but significant negative yield premium for green bonds resulting from both investors’ environmental preferences and lower risk levels. The European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (Fatica & Panzica, 2021) documents the dependency of premiums on the issuer with significant estimates for supranational institutions and corporations, but not for financial institutions. While these econometric approaches offer relevant insight into the pricing of green bonds and the incentives for issuers and investors, they do not account for the institutional particularities of social housing, a highly regulated sector usually covered by varying forms of state guarantees and subsidisation (Lawson, 2013).

ESG-labelled debt instruments & Related Legislation

Throughout the last two decades, the term ESG finance has evolved to include a large number of financial vehicles of which green bonds have become the most popular (Cortellini & Panetta, 2021). In the social housing sector, ESG comprises a broad array of tools from sustainability-linked loans to less conventional forms of finance such as carbon credits. When it comes to bonds, there is a wide variation in the sustainability credentials among the different types. Broadly speaking, green and social bonds are issued under specific ‘use of proceeds’, which means the funds raised must be used to finance projects producing clear environmental or social benefits. The issuance of these types of bonds requires a sustainable finance framework, which is usually assessed by a third party emitting an opinion on its robustness.

Sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) are an alternative to ‘use of proceeds’. Funds raised in this manner are not earmarked for sustainable projects, but can be used for general purposes. SLBs are linked to the attainment of certain company-wide Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), for example an average Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of “C” in an SHO’s housing stock. These indicators and objectives usually result in a price premium for Sustainable Bonds, or a rebate in interest rates in the case of SLBs or sustainability-linked loans (SLLs) (Cortellini & Panetta, 2021).

While there are international standards for the categorisation of green projects such as the Green Bond Principle or the Climate Bonds Strategy, strict adherence is optional and there are few legally-binding requirements resulting in a large divergence in reporting practices and external auditing. To solve these issues and prevent greenwashing, the EU has been the first regulator to embark on the formulation of a legal framework for green finance through a series of acts targeting the labelling of economic activities, investors, corporations and financial vehicles.

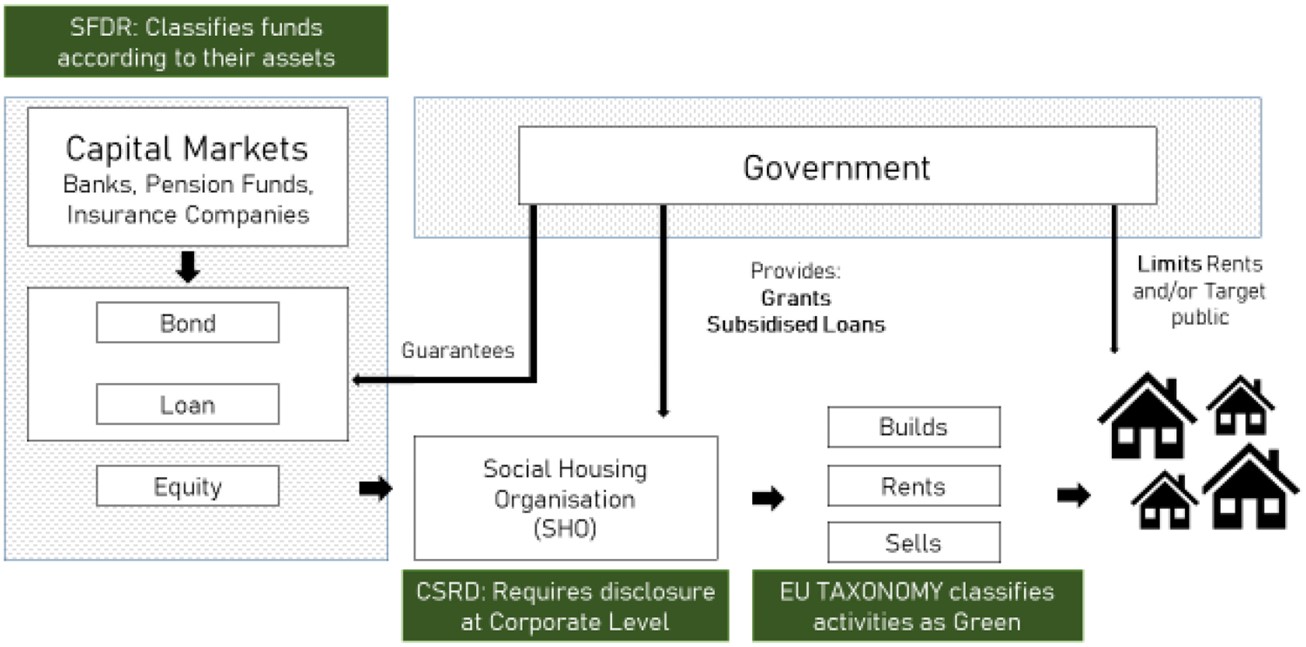

First, the EU Green Taxonomy (Regulation (EU) 2020/852) is the cornerstone of this new legislation since it classifies economic activities attending to their alignment with the objectives set in the European Green Deal (EGD). When it comes to housing, the EU Taxonomy requires specific energy efficiency levels for a project to be deemed ‘taxonomy aligned’. Second, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) (Regulation (EU) 2019/2088) mandates ESG reporting on funds, which tend to consist of exchange-traded collections of real assets, bonds or stocks. Funds are required to self-classify under article 6 with no sustainability scope, ‘light green’ article 8 which incorporates some sustainability elements, and article 9 ‘dark green’ for funds only investing in sustainability objectives. Under the SFDR, which came into effect in January 2023, fund managers are required to report the proportion of energy inefficient real estate assets as calculated by a specific formula taking into account the proportion of ‘nearly zero-energy building’, ‘primary energy demand’ and ‘energy performance certificate’ (Conrads, 2022). Third, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)(COM(2021) 189) increases disclosure requirements for corporations along Taxonomy lines. This legislation, which came into effect in 2023, will be progressively rolled out starting from larger and listed companies and expanding to a majority of companies this decade. Provisions have been made for charities and non-profits to be exempt. However, one of the key consequences of disclosure requirements over funds through the SFDR is its waterfall effect; that is the imposition of indirect reporting requirements as investors pass-on their reporting responsibilities to their borrowers. Fourth, the proposed EU Green Bonds Standards (EU-GBS) COM(2021) 391 aims to gear bond proceedings toward Taxonomy-aligned projects and increase transparency through detailed reporting and external reviewing by auditors certified by the European Security Markets Authorities (ESMA). The main objectives of these legislative changes is to create additionality, that is, steer new finance into green activities (see Figure 1).

While this new legislation is poised to increase accountability and transparency, it also aims to encourage a better management of environmental risks. According to a recent report on banking supervision by the European Central Bank (ECB), real estate is one of the major sources of risk exposure for the financial sector (ECB, 2022). This includes both physical risks, those resulting from flooding or drought and, more relevant in this case, transitional risks, that is those derived from changes in legislation such as the EPBD and transposing national legislation. The ECB points to the need for a better understanding of risk transmission channels from real estate portfolios into the financial sector through enhanced data collection and better assessments of energy efficiency, renovation costs and investing capacity. At its most extreme, non-compliance with EU regulations could result in premature devaluation and stranded assets (ECB, 2022).

In short, the introduction of reporting and oversight mechanisms connects legislation on housing’s built fabric, namely the EPBD, to financial circuits. On the one hand, the EU has been strengthening its requirements vis-à-vis energy efficiency over the last decades. The Energy Efficiency Directive (EED) suggested the introduction of Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) by Member States (Economidou et al., 2020), a rationale followed by France and the Netherlands for certain segments of the housing stock. Currently, policy-makers are debating on whether the EPBD’s recast (COM/2021/802) should incorporate MEPS and make decarbonisation an obligation for SHOs across the EU. On the other hand, legislation on green finance aims to produce incentives and oversight over investments in energy efficient renovation and new build, mobilising the private sector to cater to green projects (Renovation Wave (COM(2020) 662)).

Alignment with project research areas

ESG finance emerges as a critical driver within the research framework of RE-DWELL, emphasizing its alignment with policy and financing strategies to address housing affordability within the energy transition, particularly for vulnerable groups. The integration of ESG principles into the research framework is pivotal, as it offers a comprehensive approach to sustainable investments that extend beyond the traditional financial metrics.

The factors at the core of ESG finance resonate in RE-DWELL's research objectives, where the focus extends beyond mere energy efficiency to encompass the broader social impact of housing affordability. By prioritizing the well-being of vulnerable demographic groups, ESG finance ensures that investments contribute not only to environmental sustainability but also to the improvement of social conditions, aligning with the overarching goals of RE-DWELL's research framework.

ESG finance's commitment to environmental considerations aligns seamlessly with the energy transition objectives outlined in RE-DWELL's research. By incorporating criteria that assess and promote energy efficiency, ESG finance directs investments towards technologies and practices that contribute to reducing carbon emissions, fostering an environmentally sustainable housing landscape.

Moreover, the emphasis on social factors within ESG criteria directly addresses the challenges faced by vulnerable groups in the context of housing affordability. By considering the social implications of investments, ESG finance becomes a strategic tool for ensuring that housing solutions are not only ecologically responsible but also inclusive and supportive of marginalized communities.

The governance component of ESG principles ensures transparency, accountability, and ethical decision-making, which are essential elements in effective policy implementation. As RE-DWELL's research framework navigates the complexities of financing solutions, the governance-focused approach of ESG finance becomes integral to establishing robust structures that facilitate responsible and sustainable housing initiatives.

In conclusion, ESG finance serves as a linchpin in the research framework of RE-DWELL, offering a holistic and integrated approach to housing affordability within the energy transition. By aligning with policy objectives and financing strategies, ESG finance transcends traditional investment metrics, contributing to a future where housing solutions are not only environmentally conscious but also socially inclusive and governed by ethical practices. This collaboration highlights the transformative potential of ESG finance in shaping sustainable and equitable housing ecosystems.

References

Bertoldi, P., Economidou, M., Palermo, V., Boza‐Kiss, B., & Todeschi, V. (2021). How to finance energy renovation of residential buildings: Review of current and emerging financing instruments in the EU. WIREs Energy and Environment, 10(1), e384. https://doi.org/10.1002/wene.384

CBI. (2021). $500bn Green Issuance 2021: Social and sustainable acceleration: Annual green $1tn in sight: Market expansion forecasts for 2022 and 2025. https://www.climatebonds.net/2022/01/500bn-green-issuance-2021-social-and-sustainable-acceleration-annual-green-1tn-sight-market

Clarion. (2020). Clarion Housing Group raises £350m in record breaking sustainable bond issue. https://www.clarionhg.com/news-and-media/2022/04/11/clarion-350m-in-record-breaking-sustainable-bond-issue

Cortellini, G., & Panetta, I. C. (2021). Green Bond: A Systematic Literature Review for Future Research Agendas. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(12), 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14120589

Conrads, C. (2022). Policy and regulation in the area of tension between shaping the ESG transformation and growing regulatory pressure. In T. Veith, C. Conrads, & F. Hackelberg (Eds.), ESG and Real Estate: A practical guide for the entire real estate and investment life cycle. Haufe-Lexware. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.tudelft.idm.oclc.org/lib/delft/detail.action?docID=6998863

European Central Bank. (2022). Good practices on climate-related and environmental risk management: Observations from the 2022 thematic review. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2866/417808

Economidou, M., Todeschi, V., Bertoldi, P., D’Agostino, D., Zangheri, P., & Castellazzi, L. (2020). Review of 50 years of EU energy efficiency policies for buildings. Energy and Buildings, 225, 110322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2020.110322

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (2007). Disagreement, tastes, and asset prices$. Journal of Financial Economics, 23.

Fatica, S., & Panzica, R. (2021). Green bonds as a tool against climate change? Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(5), 2688–2701. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2771

Hachenberg, B., & Schiereck, D. (2018). Are green bonds priced differently from conventional bonds? Journal of Asset Management, 19(6), 371–383. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41260-018-0088-5

Housing Europe. (2020). The Cost of the Renovation Wave. https://www.housingeurope.eu/file/948/download

Lawson, J. (2013). The use of guarantees in affordable housing investment—A selective international review. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

Zerbib, O. D. (2019). The effect of pro-environmental preferences on bond prices: Evidence from green bonds. Journal of Banking & Finance, 98, 39–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2018.10.012

Reuters. (2022). German officials raid Deutsche Bank’s DWS over “greenwashing” claims. https://www.reuters.com/business/german-police-raid-deutsche-banks-dws-unit-2022-05-31/

Related vocabulary

Building Decarbonisation

Housing Affordability

Housing Governance

Housing Policy

Housing Regime

Just Transition

Measuring Housing Affordability

Social Housing

Sustainability

Sustainability Built Environment

Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 06-11-2023

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 17-10-2023

Read more ->Area: Policy and financing

Created on 16-02-2022

Read more ->Area: Policy and financing

Created on 01-07-2022

Read more ->Area: Policy and financing

Created on 24-02-2022

Read more ->Area: Policy and financing

Created on 03-06-2022

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 17-10-2023

Read more ->Area: Policy and financing

Created on 17-06-2023

Read more ->Area: Community participation

Created on 08-06-2022

Read more ->Area: Design, planning and building

Created on 24-06-2022

Read more ->